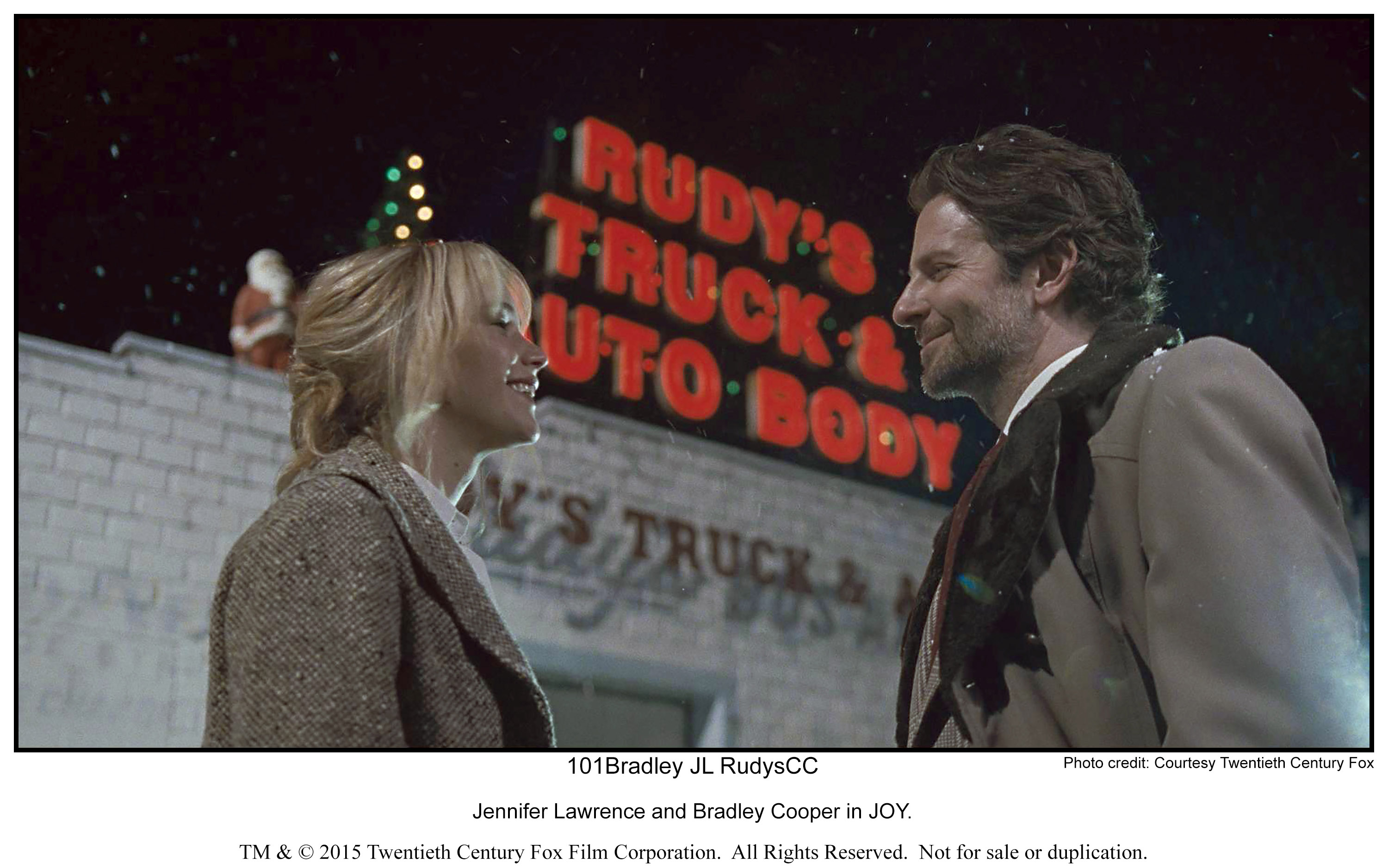

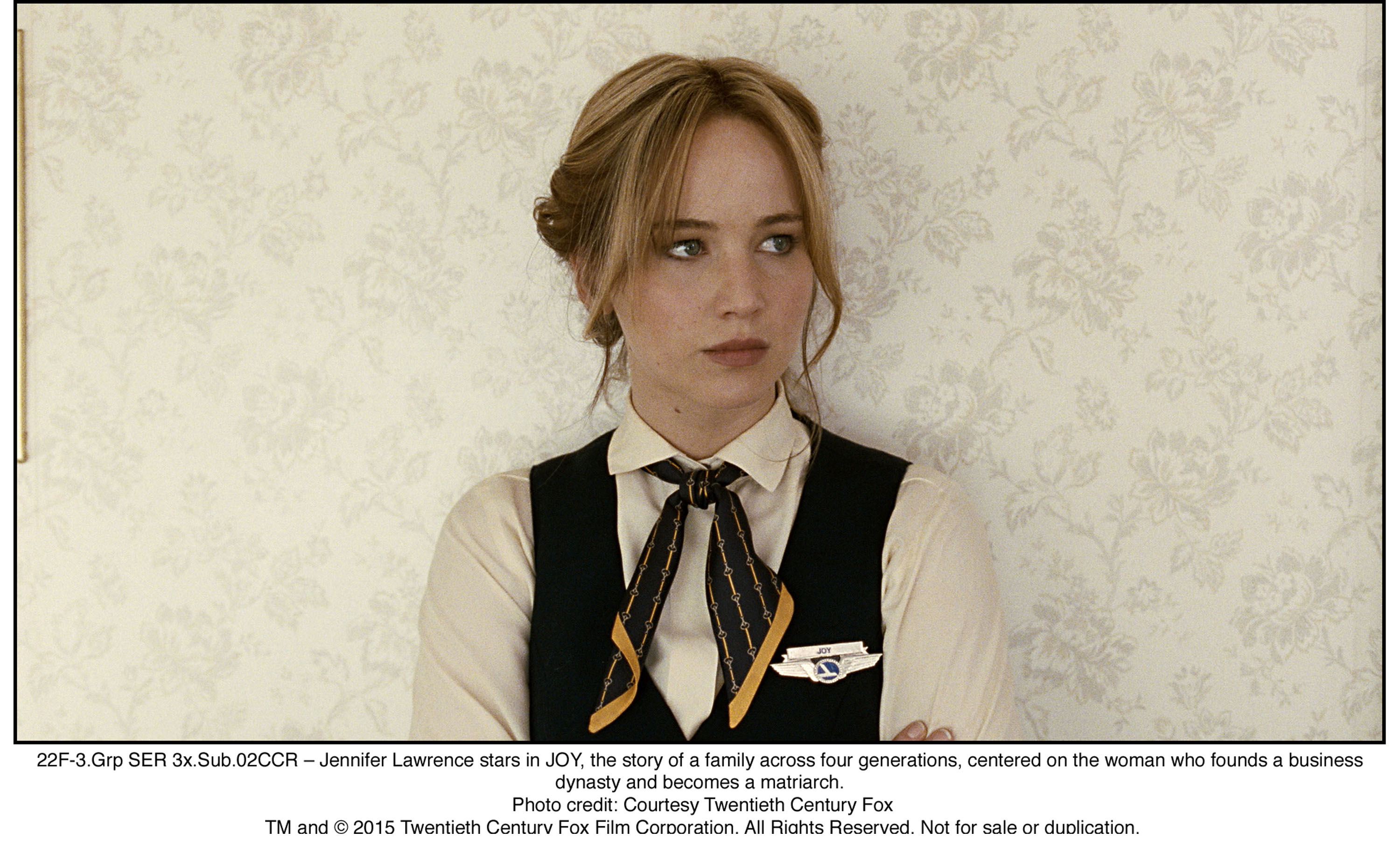

Art of the Cut caught up with Oscar winning editor, Tom Cross, as he was cutting his upcoming feature, “La La Land.” We talked mostly about his last feature, “Joy,” but also had an extensive exploration of his editing of the film that won him an Oscar, “Whiplash.”

HULLFISH: You’ve been nominated for awards by your fellow editors. You won an Oscar for the editing of “Whiplash” which has been widely cited by other editors for its editing. How do you judge the work of other editors?

CROSS: It’s very difficult to truly judge the work of other editors because you usually don’t know what they had to work with. You don’t know what storytelling choices they made. Also, editing is often invisible by design.

In general, if I’m emotionally engaged, then I feel the film editing must be functioning well. If I see a great performance, then I like to think that it’s well edited because that performance is sculpted from hundreds or even thousands of pieces.

Sometimes, the editing is more obvious because the style or architecture of the storytelling is more overt. The filmmakers play with time or the audience is aware of the pace of the story, or the rhythm of the cuts. Those are often the films that get noticed for editing because the craft is easier to see. If I see a film or a scene that really affects me, I want to go back and examine it to try to understand how it was put together. That was the case with “Sicario”, a film I loved which was directed by Denis Villeneuve and edited by Joe Walker (see Walker’s Art of the Cut interview here). With that film, I see a movie that really was shaped in the editing room. It has beautifully crafted action but also shows a confident use of time and pace in order to create tension. The sequence showing the convoy crossing the border and driving through the streets of Juarez is elegantly and masterfully constructed.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=13wqRFYBE8M

It’s a very prolonged sequence that serves to introduce us to the characters and their setting but also to create an enormous amount of anxiety.

At a glance the scenes appear expository — the convoy moves from one location to another — and could easily have been abbreviated and shortened. However, a choice was made to really inflate the time frame and build the anticipation in a very slow, and deliberate way. As the convoy navigates the winding streets, it’s like a rubber band keeps getting stretched and stretched and you’re just on the edge of your seat waiting for it to snap back. This feeling is caused by an editorial choice. These are the types of sequences that are usually a target for those that are merely concerned with content and not the form. I’m glad that the filmmakers had the room to let the buildup breathe. What you see in that film leaves an impression. You experience it. It’s memorable.

The drum playing in “Whiplash” – the sound of it – has an inherent rhythm that sets a metronome in the minds of the viewers. Its very existence in a scene invites a relationship with the image and sets up a sonic pattern that the picture can answer. Damien wanted to play off of that and employ fast editing, jarring smash cuts, and short insert shots coupled together to punctuate. He wanted the cutting to feel very swift and precise almost as if the character of Fletcher was editing the film. At times, he really wanted the cuts to feel brutal and violent. He told me that he wanted the music scenes to feel like the boxing scenes from “Raging Bull.”

http://moviola.com/inside-hollywood/whiplash-tom-cross/#2

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9qrGw1Iq1aA

But I don’t think it was merely the fast cutting that grabbed people’s attention. I think part of it was Damien’s choice to apply these stylistic flourishes – flourishes more expected in an action film or sports film – to a story about jazz musicians. At the same time, however, Damien was very clear that only certain scenes should feel like that. He didn’t want to impose this brutality or cold precision on every single scene. So it would really depend on what character we were cutting. When it came to scenes of Andrew and his girlfriend Nicole, Damien wanted the editing style to be much more traditional, slower and more romantic. The same is true of the early scenes with Andrew’s Dad. He wanted them to play classically and invisibly. The exception would be the dinner scene when all the family members are talking around the table and the Dad is there. That’s a scene that starts off a certain way but very quickly escalates to a very fast paced, cold flurry of cuts. That’s because Damien wanted it to feel ruthless and wanted to show how fast Andrew’s come-backs were and how he was cutting his father down with the dialogue. But in general the scenes with the other people – the Dad and Nicole -were much more languid, whereas the scenes with Fletcher were snappy and violent.

HULLFISH: That’s interesting… I don’t know if you’ve heard that “Whiplash” earned the nickname, “Full Metal Drum Set.”

CROSS: (laughs) That’s a major compliment. I heard someone refer to it as “Full Metal Juilliard.”

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about how you were – as the editor – a storyteller in “Joy.”

Cross: I felt very lucky to work on “Joy” because I’ve always been a big fan David O. Russell. I’m also a fan of all the editors on that film, Jay Cassidy, Alan Baumgarten and Chris Tellefsen. I grew up watching movies all those guys cut, so being able to work alongside them was another dream come true. Before filming began, they told me what I eventually learned: that David is a remarkably precise story teller when it comes to emotions. He really wants to calibrate each character’s emotions in a way that feels very authentic, and he doesn’t want anything to be false or feel constructed. He wrote this very dense script, which was incredible and full of so many amazing details and character riches. When he shoots, he makes very specific choices regarding camera and performance but he also shoots a lot of different options. He’ll shoot the characters going off on these branches – and I don’t even like to call it improv because it’s not really. He’ll have the characters do a pass on the scene with a certain level of emotion and then he’ll work with the actors to re-calibrate them and then do a different emotional pass. Sometimes he’ll shoot scenes where you’ll have a little moment with another character nested within that scene, but he may shoot a different scene somewhere else in the movie and have that same beat and that same character nested into that scene. He does that because he wants to give himself options in the editing room, with where to put a certain beat. He is really brilliant at this because he knows that there’s a transformation that takes place when you commit something to film. What you get in dailies is often different from what was originally envisioned. So the story itself winds up having some elasticity and he just likes to prepare for that.

We found the same thing on “Whiplash.” The script was tight as a drum, no pun intended. It really felt like it was perfect, but once it was shot and you got in the editing room – surprise! Surprise! – you learn there’re a lot of things that you don’t need and that less is more. At the same time you also find things that seem extremely clear in the script are actually confusing when you put the pieces together. So you have to re-engineer it in a certain way. David really tries to keep that in mind. He knows that you might want to put a story beat somewhere else in a movie. So he’ll shoot that story beat in a couple of different places. He knows that he’s going to work closely with the editors to find the perfect place to put that beat.

David doesn’t get hung up on physical geography and space. He is the first one to tell you to give that up in exchange for something that feels emotionally right. He is very specific about visual style – just look at the opening shots of “The Fighter” or “Silver Linings Playbook” – but ultimately, it’s the emotional continuity that drives the story and holds the film together. Everything else is secondary. I admire him for that because not every director is good at remembering that.

HULLFISH: When I interviewed Jan Kovac about “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot” he said that they also calibrated those performances like that so that you have options: to decide on the warmth or the coolness or the humor or the danger in a performance. But then it’s up to the editor and the director in the edit suite to decide what is the right calibration of that performance.

CROSS: That’s right. Film editing can be challenging because your target is often a moving one. When you start cutting, you’re working with David on scenes or specific sequences. You choose certain takes or pieces that you feel serve the desired story points and emotions. Once you start looking at the broader picture, when everything is assembled together, you might switch out performances because the context has illuminated a piece or moment that feels out of place. David is not afraid to re-engineer something he’s created in the pursuit of emotional truth.

HULLFISH: What was the schedule on “Joy”? Why were there so many editors? Four.

CROSS: Jay Cassidy and Alan Baumgarten had worked on David’s previous film, “American Hustle,” and the plan was for them to cut the film, but as happens with schedules in the film business, “Joy”’s start date shifted in a way that neither Jay nor Alan were immediately available. Jay could start a little bit, but not full time. They really were looking for another editor to start the movie with them and start working with David when he got back from shooting. When Producer John Davis asked me if I would be interested, I leapt at the opportunity. Before cutting started, I met with Jay and Alan and they were very welcoming and got me up to speed in terms of how David likes to work. So Jay & I started the movie and by the time shooting wrapped, Alan had joined us. Soon after, David brought on Chris Tellefsen who he had collaborated with on “Flirting with Disaster”. It ended up being the four of us cutting at the same time, which was pretty amazing. Because of the way David likes to explore different story branches, you need several editors to work with him and keep up the forward momentum. Eventually, Chris & I left for prior film commitments and Jay and Alan continued working and finished the film.

HULLFISH: How did that collaboration work? Did you guys just pick scenes? I know you had to do kind of everything at the beginning, but what was the process of that collaboration with the other editors?

CROSS: When Jay and I started, we just took whatever scenes came in. We started cutting them and sometimes we would say, “Why don’t you take this scene and this scene because it connects up with the other scenes you’ve already cut so you’ll have a nice long run?” So we would do that. By the time Alan started, David was already back from location and he broke down the movie into ten sections. That’s the way he saw the story: ten emotional movements, and that made it easier to divide up the cutting. Initially, David left it up to the editors to decide which parts to work on. I had already cut a lot of material from section one so that’s the section that I took. Jay had already been working on a huge chunk of a certain section so he took that. As time went on, David gave each person different assignments on different parts of the film. This meant that each editor often worked on scenes that someone else originally cut. This approach worked because the personalities of all the editors meshed well. David was able to utilize all of us as one unit in a way. Often when one editor screened some cuts for David, the others would be invited in to watch and give feedback.

HULLFISH: Tell me about how you like your assistant to set things up. How do you like a scene to be organized in the bin? When you watch dailies, what is your approach? Are you watching them projected or are you sitting at your Avid?

CROSS: Since I was an assistant for many years I saw a lot of different approaches. I find that my methods kind of evolve with each picture. I try not to be so rigid about how I do things, although I’m probably like a lot of other editors: just a little compulsive by default. I’ve always been a really visual person. I respond more to the visual rather than text. I like to work in Frame view (using thumbnail images) and I have my assistant arrange the master clip frames in a horizontal row starting from left to right. Each row is a camera setup. If there are multi camera clips, they group clips in a certain way in the bin. I will have the script supervisor’s notes next to me but I like to have my assistant transfer some of the comments about each take into the name of the Avid clip. That’s something I picked up from John Axelrad. At a glance it might look counter-intuitive and messy to some but it actually helps me work more quickly. For me, I like to just focus on what’s in the Avid. It allows me to become less dependent on the paperwork when I’m in the heat of cutting. My assistant abbreviates so that there isn’t too much information polluting the name of the take.

I always work with picture scene cards on my wall. I know a lot of editors that do. With the representative frame from each scene, you can look at the picture and instantly know what the scene is. You almost don’t need the scene number. My Assistant creates these cards in a Filemaker Pro layout. For me it’s a road map for the entire movie and something I can look at to find my bearings. Directors and Producers also like to use to it to communicate their ideas and notes.

HULLFISH: And is that stuff that’s up on the wall – is that helping you in the scene itself or with the overall structure of the movie? What do you find that that helps with?

CROSS: They help me with the overall structure and remind me to think of the big picture. I believe that Walter Murch does a representative card for every set up. (Each camera angle or lens change within a scene.) That’s pretty amazing.

HULLFISH: So with your bin laid out, what is your approach to a scene? Do you use select reels or do you just find an entry point into the scene and go chronologically through the scene?

CROSS: I’ll always start by watching all the dailies for a particular scene before I make a cut on that scene. Often, I’ll look at the last take of every set up in a scene first, just to get a quick glimpse of the coverage shot. Then I’ll immediately go back to the first take and the first set up and watch every take in order. I’ll add locators or markers in the master clips on moments I like or add comments as needed. As I’m watching each take, I try to immerse myself in the rhythms of the performances. As I start to move from one setup to another, I also start retaining the coverage and start cutting it in my head.

Of course, each director works differently and this approach to viewing dailies from the end doesn’t work for a David O. Russell film. Looking at the last take doesn’t really give you a full inventory of his material. You really benefit from watching his dailies in order from the 1st take onward because you get a better feel for his process and how the performances and camera evolve. Each camera setup is not easily definable in terms of how to use it. They’re usually chocked full of so many rich details and pieces and it’s important to really focus and catalog all those moments. In all cases, you’re looking for whatever connective tissue might help you join two pieces of film together.

For traditional dialogue scenes, I don’t do select reels unless there’s a lot of improv. Usually, I’ll just mark favorite moments in the master clips.

If I’m working on an action scene, a montage or something purely visual, I’ll string the dailies together in a long sequence and then cut it up so that I have selects by the end. Then I’ll dupe that sequence and try to cut a scene out of it or try to create a structure for it.

On my current film “La La Land,” I watched dailies standing up. I have one of those electric desks that lowers and raises. I also have a small treadmill under my desk and I’ll walk and mark takes while I’m viewing rushes.

HULLFISH: I’m standing at a standing desk right now as a matter of fact. I love it.

CROSS: I tried using a standing desk from time to time when I was an assistant. I liked it but never really committed to it. Then when I worked on “Joy,” I started to feel stiffness in my back so I figured that it would be better to stand. “La La Land” is the first time I’ve done it as an editor. When I’m editing with Damian Chazelle, I sit most of the time. Part of the reason is how I have my room set up. When I sit, I’m closer to the sweet spot for sound because I have my console behind the couch.

HULLFISH: You sit behind the director?

Yes. Jeff Ford was the first film editor I knew who set the room up like that. One time I visited his cutting room and thought he had a great idea. I like it because it let’s the director focus on one big monitor. I also want to be able to present the cut with the director centered in regard to the stereo speakers. I always struggled with the more traditional old Avid set up. Things were always more off center and the director would be looking at the big monitor but also be faced with all the other extra monitors and equipment. So then I thought “Why even have the other monitors in view?” I have my post PA put up black duvateen on the wall behind the monitor just so it’ll black out even more. The goal is to become immersed in the movie, hear it from the sweet spot and ideally have the rest of the room fall away.

HULLFISH: It would be interesting to see your editing suite. Talk to me about the temp music and your approach to temp music for “Joy” – what you used for temp music. Some directors don’t even want temp music under when they watch stuff.

CROSS: David had his own carefully curated library that he wanted to try in the film. His knowledge and love of music and cinema are deeply intertwined. He usually has very specific songs in mind for specific scenes. There are also songs that he loves but hasn’t placed yet. We’d have long meetings about music and where he thought songs might go. He created a music catalog of his library with comments, scene suggestions and emotional tags that he shared with the editors.

With “Joy” you often found beautiful pieces and emotional moments that you wanted to put together but they were discontinuous in a traditional sense. My first instinct as an editor is to try to pin down every cut, every join, in a classical way. And that is sometimes a wall. David’s filmmaking pushes the music to shatter that wall. It frees you from rigid formality and helps you create a new architecture that’s the style of David O. Russell. The songs become an emotional thread that hold the moments together. You can see that in “Joy”. Music is a common element in all of David’s films. Look at the iconic opening of “Three Kings” with it’s muscular hand offs from one cue to the next. He’s a director that uses music in a way like no other.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about getting past the first assembly on any of your movies. Where does it go from there? That point where you have put everything together the way it is in the script … Now what has to happen?

CROSS: I always try to make my first cuts as polished as possible. Like most picture editors these days, I put in temp music, SFX and backgrounds. At the same time, I never see it as something precious that needs to be hung on a gallery wall. A first cut is the best way for me to keep an eye on things and protect Production while they’re shooting and also the best way for me to get to know the footage before working with the director. I find that the assembly can be very traumatic for many directors. They really don’t like watching them. As an editor it’s important to not take that personally because it’s not about my work necessarily (although it can be). It’s more about the director seeing this far-from-perfect version of their story and it’s hitting them like a ton of bricks. There are so many things wrong and they don’t really know where to begin. Many of them are choices that I made that the Director would like to change and some of them are things that didn’t translate well from the script. It’s overwhelming. It’s my job to be realistic about the problems but it’s also my responsibility to be supportive, assuage fears and start steering the process in a constructive direction. At that point, I remind the director that the best way to tackle the entire film is one scene at a time.

In the case of “Whiplash,” Damien Chazelle watched the first cut of it and he turned to me and said “Do you think we have a movie here?” I said, “Absolutely. This movie is going to be incredible.” Then I got up and pointed to all the scene cards on the wall and started going through the film. I assessed each scene and talked about how much work I thought needed to be done – what the goals should be. He told me later after we had finished editing that he was completely depressed after he saw the first assembly. He was actually worried that the movie was going to be terrible but that I kind of talked him out of it.

HULLFISH: You had to walk him back from the edge of the cliff…

CROSS: …without me even knowing it. It just shows you no matter how confident and brilliant the filmmaker is, they can still be overwhelmed. In the case of “Whiplash” and “La La Land” Damien made a decision to just start at the end of the movie, because he had a really good idea of what he wanted to do with the final scenes. He was really anxious to dive into them because in some ways, they were the reasons for making each film. In the case of “Whiplash,” he really wanted to jump to the last climactic scene: Caravan. (the great and complex jazz standard) We worked on that first and got it into a shape that we were very happy with. It re-invigorated and recharged both of us because we felt like we had accomplished something and that we had an ending that we were proud of. Then we felt comfortable enough to go back to the very beginning and start working towards the end.

HULLFISH: Do you remember how long it took you to get Caravan into good shape? (the following is just a section of the finale)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=twKsU1Qv4k8

CROSS: I don’t remember the exact amount of time. The entire schedule was somewhat of a blur because they shot in September and we had to submit to Sundance in early November. We locked picture December 6th and played Sundance in January so it was the fastest post schedule I’ve ever had. But in the end, Damien had it very well planned out. He had storyboards for every scene. He had animatics for every big musical scene, so I always had Damien’s blueprint. What we found, especially with “Caravan,” was that we really had to get in and get our hands dirty and shape the scene emotionally. Initially, I cut the scene as closely as possible to the animatic. We watched it and both thought it was kind of mechanical. It didn’t really work emotionally but at least we had a framework. So what we had to do was find the best bits of our characters and find the best places to put those moments. A lot of them were looks to one another. Eyes meeting. But they were also emotional beats on their faces that helped show their character arcs from the beginning of the scene to the end. That’s where the scene gets its true power. Once you lay the foundation of the characters’ emotions, you can kind of build everything else off of that. Most of the big camera moves were pre-planned like the sequence of whip pans from JK Simmons conducting to Miles Teller drumming. All of that was planned in a very specific way. Therefore, our biggest task was to figure out how to inject our characters around those beautifully planned shots. Our figurative reference for that was “The French Connection” because we talked about the iconic car chase and how it gets a lot of its power – most of its power – from the face of Gene Hackman. The other stuff – the subway and the car photography –is significant but it really gets its full value from Hackman’s reactions and emotions. I think that’s true in most memorable action scenes: The boxing scenes in “Raging Bull” are a potent mixture of action-oriented photography – the inserts of blood and gloves – but also character. They’re amazing in large part because, Robert DeNiro’s performance is so expressive. His face gives you so much. The crisp shots of blood dripping from the rope and mouthpieces flying out in slow motion, bring something already striking to an entirely new level.

HULLFISH: While we’re talking about character providing context to action, talk to me about finding performances and sculpting performances.

CROSS: The performances are the most important element for the movie. You really want the characters to feel real and to move through the story beats in a way that makes sense to the audience. From scene to scene you need character arcs to be clear. When you’re working with performances by Jennifer Lawrence or J.K. Simmons, you’re lucky. You get gold to work with and I’m very conscious about protecting their work and the characters that they’ve created. Sometimes, you can let something play and not cut at all. However, as we refine how the story is being told, we must often refine or edit performances to fit. I’ll do that by playing with beats and speed of performance. I will combine performances – if I have an over the shoulder shot or a two shot I’ll split the screen and line up the performances differently. If the Director feels the need for more of a pause on one character and we’re over his shoulder, I’ll split the screen and hold one character and then rock him in reverse and have him roll forward and rock him back until I need that character to stop talking. I definitely use visual effects to manipulate performances in a way that feels appropriate to the scene and appropriate to the characters. That’s something that I end up doing in all movies and I definitely did it in “Whiplash.” So on one hand people notice the overt cutting style, but at the same time there’s also a lot of invisible editing. One scene in particular is the rushing or dragging scene…

HULLFISH: …which basically turned into psychological torture…

CROSS: Exactly! Fletcher is slapping his face and then taunting him because he starts crying which was a scene where I did split screens and lined-up what we felt were the most powerful pieces of performance. Miles gave an amazing performance overall but our favorite take of his didn’t have the tear we wanted at that right time. We found that there was a great tear later in the same take, when he starts crying at the end of the scene. Damien wisely shot it with two cameras – a two shot and also a close-up – so I was able to recycle that later tear moment and use it earlier by doing a split screen. So I’ll do things like that when necessary and my hope is that no one spots it.

HULLFISH: I certainly didn’t. I’m going to have to go back now and watch that. If we can get back to “Joy” to wrap this up, I was wondering if you could walk me through a challenging scene. What made it so difficult? What element or trick or moment “broke” the scene for you and made it work? Why do you like the editing in the scene?

CROSS: When I first met Jay Cassidy, he talked about editing with David and how the distance you travel from your first cut to your final cut may be vast. He illustrated this by showing me a scene from “American Hustle.” It was the scene early in the film when Irving, Richie & Sydney meet with Mayor Polito in the hotel room and try to bribe him with a suitcase full of money. The first cut version of it was a big meaty dialogue scene that played in real time and was in the area of 2-3 minutes long. In the final cut that made it into the movie, that same scene was firmly distilled down to a handful of short, concise shots.

On “Joy”, I remember cutting the scene when Joy is handling a crying baby and trying to wake a hungover Tony who is sleeping on the living room couch. It was a tough scene to cut because David and the actors did different emotional passes and also went down different story branches. There were many options, including versions of the scene spoken completely in Spanish which I don’t speak or understand. The performances had large arcs in them in that the scene started with them arguing and yelling and ended with them quietly mourning that their relationship is over. There were great pieces and beats in all the branches and versions but I found it very challenging to join them together and have them feel connected. I continued working on it with David but it never quite hit the mark. Eventually, David wanted to try threading music thru it and that is what “broke” the ice on the scene for me. The musical foundation held the pieces together and allowed me to distill even further. Suddenly, disparate pieces stuck together and communicated a completely unified, emotional experience. When I had to jump onto my next project, Alan & Jay continued to finesse the scene. The scene evolved more and the music become the Bee Gees track “To Love Somebody” and that’s in their now. It’s heartbreaking and powerful. There were many more breakthroughs – both big and small – like that on the film. I get excited by that type of editing because it pushes me to think about cinematic grammar in a different way. All of what we do is a distillation process but David’s version of that on “Joy” was truly eye-opening and inspiring to me.

HULLFISH: Thank you for all of the time you’ve given me.

CROSS: My pleasure.

To read more interviews like this one, follow THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now