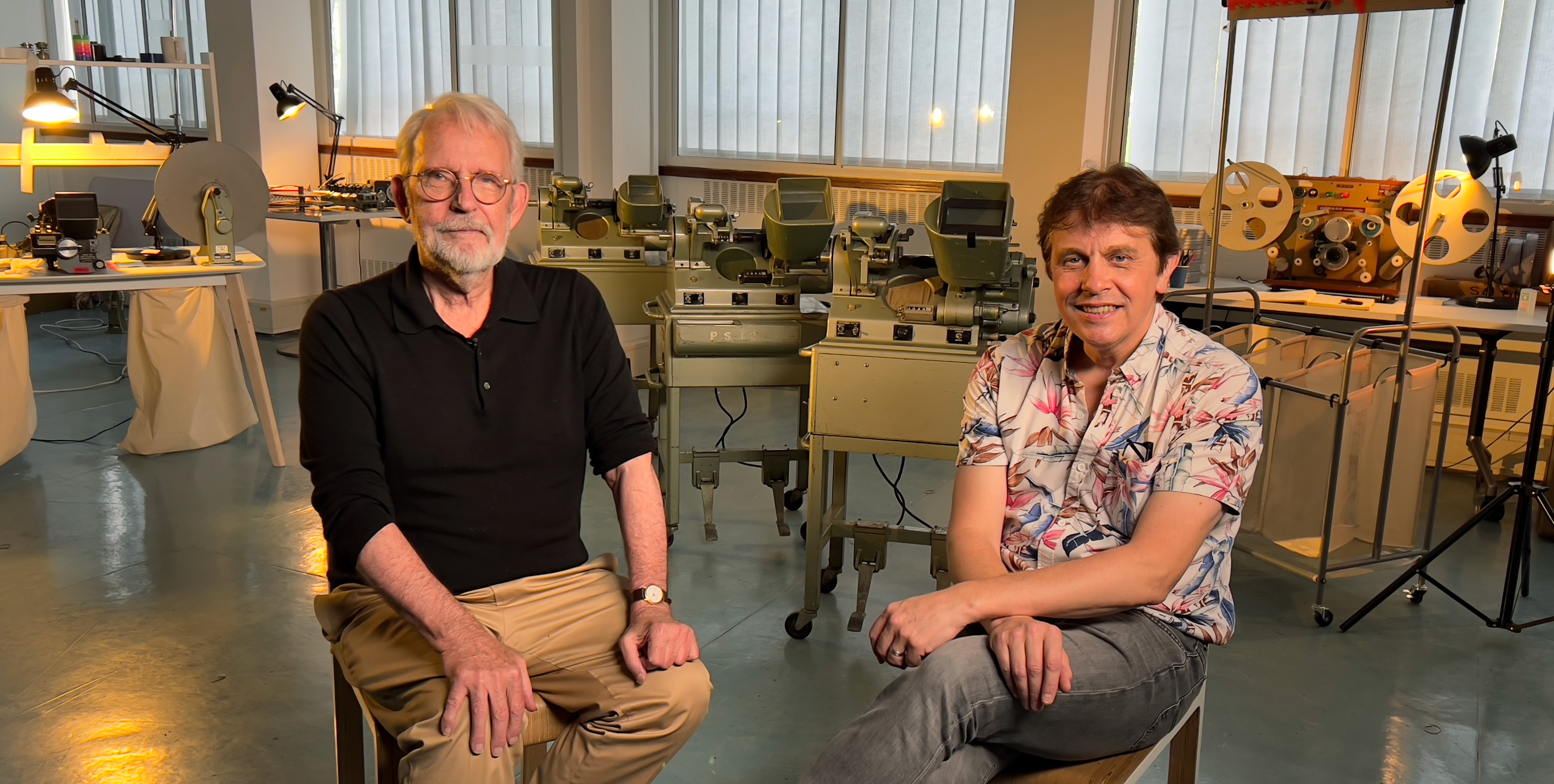

Walter Murch is not one to sit around quietly in retirement. For the past year or more he’s been in London working on a book and giving lectures, along with numerous film projects. Murch describes one of these as “a love letter to the Moviola.” Called Her Name Was Moviola, the documentary is about the history of the machine that defined film editing technology for three-fourths of the last century. Invented in the early 1920s, the Moviola hits its centennial anniversary.

___________________________________________

Oliver Peters: Walter, please tell me about the Moviola project.

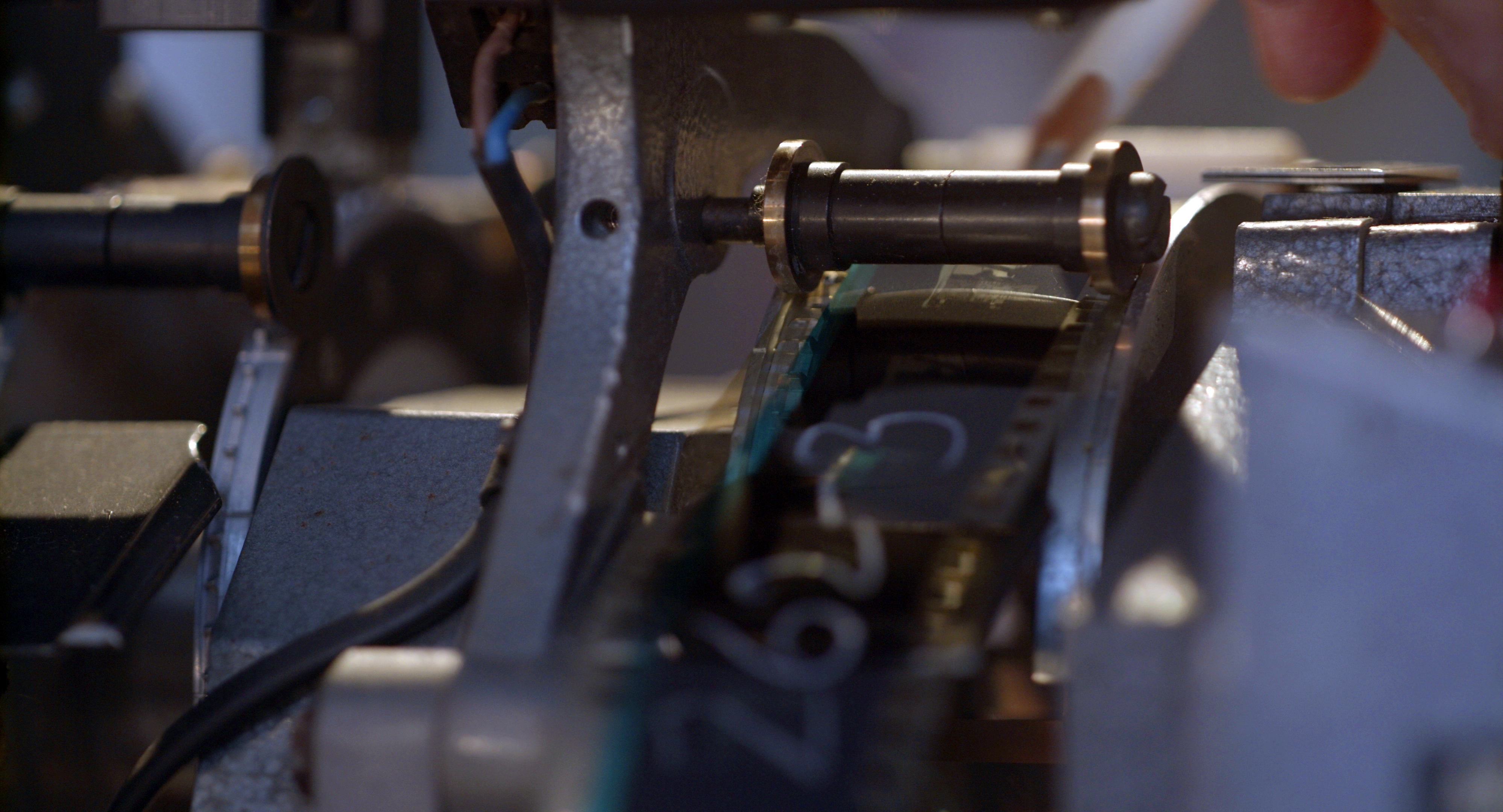

Walter Murch: Moviola was an idea that I cooked up fifteen years ago, I think. The simple idea is to recreate an editing room from half a century ago, 1972, with what you would have – a Moviola, a rewind bench, a synchronizer, trim bins, an Acmade coding machine and pressure sensitive tape. Plus, something to cut. We found a home for it at the University of Hertfordshire, which has a cinema program. Howard Berry, the head of post-production there, put together crowdfunding through IndieGoGo. Also some money was kicked in from people like Dolby.

We convinced Mike Leigh, the British director, to give us the digital files from one of his films, which turned out to be Mr. Turner (2014). We took those files and reverse engineered them to print up 35mm film in 1.85:1 aspect ratio and the sound onto magnetic stripe film. That was probably the hardest thing to get, because nobody deals with mag stripe anymore. I don’t know where Howard got it, but he was checking with post-production people here in London and combing through the catalog on eBay and eventually put together everything we needed.

I worked with my long-time British assistant, Dan Farrell, who I met on Return to Oz back 40 years ago. We had about 70 minutes of dailies for two scenes from Mr. Turner and treated them just as you would have back then… The lab has delivered the dailies from yesterday. OK, start syncing them up. Dan and I were wired up with radio mics and it was being covered by two tripod cameras, plus an iPhone with Filmic Pro for extreme close-ups. Dan and I were giving what you might call ‘golf commentaries’ describing the process. And occasional reminiscences about disasters that had happened in the past.

Next, these were synced up and screened. I took notes the way I used to on 3 x 5 cards. We printed Acmade numbers on the film and the sound to keep it in sync using the British system. That’s a little more work than the American system. The American system starts at the beginning of the roll and runs sequential numbers all the way through. Here in England, you stop at the end of every take and reset the footage number to zero, corresponding to the clapstick. For example, if you are 45 feet from the clapstick, then there is a number that tells you that you are 45 feet into this take. You also have at the head of it what set up it is and what take it is.

Dan did all of that and broke it down into little roll-ups, put tags on them, filled out the logbook, and then turned it over to me. Then I started cutting the two scenes. I didn’t have a script. I just cut it using my intuition. I had seen Mr. Turner five months earlier. So, just based on the coverage, how would you cut this together? That took about two days. And as I was cutting it together, I gave a running commentary about what I was doing technically and also creatively – why was I making the cuts where I did and why did I choose the takes that I did. It wound up being about 750 feet long, three quarters of a reel.

Did you have any script supervisor notes or anything like that?

No. I was riding bareback. [laugh] To tell the truth, that’s what I usually do. I only refer to the script supervisor’s notes on a film if there’s really some head scratcher. Like, what were they thinking here? Usually – and it was certainly the case here – it’s very obvious how it might go together.

We wanted to screen it in a theater with double-system sound, but that was impossible. There is no place in London where people have maintained a mag dubber that can sync up with a projector.

I would imagine that sort of post-production gear – if it still exists – probably isn’t in working condition.

Right. You know, it was amazing enough that we found somewhere to transfer the sound from digital files to mag. Howard found a place owned by a guy who’s into this stuff, maintains it, but mostly specializes in projectors. He had a mag recorder, but didn’t really know how it worked, so the two of them worked it out together and managed to get the transfer done. He’s probably the only person in London who still has that working machinery.

Anyway, we needed to screen it, because we were going to show it to Mike Leigh. Howard works frequently with the Stanley Kubrick estate. So we drove out there and they kindly let us use Stanley’s Steenbeck, which he bought for The Shining. It still had the original cardboard-core power transformers in the feet, which were dangerous and tripping the fuse, so as part of the production we also repaired the Kubrick Steenbeck and it then worked perfectly!

Mike arrived and we screened the scenes for him. At the end his only comment was, “You used too much of the sailboat.” [laugh] In the dailies there was a shot of a sailboat anchored off the coast. They also had shots of William Turner – the actor Timothy Spall – looking out a window at the ocean. So I put those two things together. I asked, “Why did you shoot it then?” And he said, “The cameraman shot it just because it was there.” It was one of those shots.

I guess he figured it would be useful B-roll.

Exactly. It’s a seagull type of shot. Use, if necessary. I had used it three times at transition points – seagull points. Interestingly, he said, “If you use something three times, it means it’s important,” which is true. It means that at some later point, somebody from this boat is going to come ashore and murder people or find treasure or whatever.

After that, I recut the scene and used only one shot of the sailboat. Then we pulled out a laptop and looked at Mr. Turner streaming and discovered how those scenes had actually been cut in the film. Essentially they were very similar. It’s that old question – give the dailies to two different editors, what do you get? In Mike’s version, the dialogue scene starts on the master and then goes into closeup. And once he was in close ups, he just stayed in close ups. I didn’t do that. In the middle of the scene the conversation changed completely and then got into more serious stuff in the second half. I used that as a carriage return, so to speak, to the change of topic. I cut back out to the master and then went in again. It’s minor thing and that was essentially the difference there.

What was the experience like to go back in time, so to speak – working with a Moviola again?

I hadn’t cut any dailies on a Moviola since 1977, 45 years ago. Dan had not done anything on a Moviola since 1994. But it all came back instantly. There was not the slightest hesitation about what any of this stuff was or how we made it work. Interestingly, that’s very different from my experience with digital platforms.

Let’s say I’m cutting a film using Avid and finish the work. Then three months later I get another job using the same Avid. In those three months the muscle memory of my fingers has somewhat evaporated. I have to ask my assistant questions similar to, “How do I tie my shoelaces?” [laugh] Of course, it comes back – it takes about three or four days to get rid of the rust. Then in about a week I’m fully back.

So that’s an interesting neurological question. Why does editing on the Moviola not have the slightest evaporation in 45 years, whereas editing on a digital platform that you are very familiar with start to evaporate if you are away from it for a few months? I think it’s because every skill in Moviola editing is a completely different set of physical muscular moves: splicing is different from rewinding is different from braking is different from threading up the Moviola, etc. etc. And each of them makes a different sound. Whereas the difference between ‘splicing’ and ‘rewinding’ in digital editing is simply a different keystroke.

People in the business have this fascination with vintage analog gear, whether it’s film or audio. Is it just that touch of nostalgia or something different?

The basic idea behind the Moviola film is that if we don’t do it now it will disappear from history. It was difficult enough now in 2022, which coincidentally is the 100th birthday of the Moviola. The first one was built in 1922. If we don’t do it now, it will become exponentially more difficult. Not the machine itself. I think they’ll always hang around, because they’re iconic, like ancient sculptures. But ancillary equipment like mag film was really hard to get. Also hard was the pressure-sensitive thermal tape for the Acmade printer. We eventually found it. But if we hadn’t found those tapes, we couldn’t have made the film. It was as simple as that. Without that specific tape, all of this inverted pyramid would have just collapsed.

Every film in Hollywood from about 1925 until 1968, let’s say, was cut on a Moviola. Before 1925 cutting was done without any machine. The editors were just cutting by hand, assembling shots together and then screening the assembly. So the screening room was in essence their Moviola. They would take notes during the screening and then go back to the bench and trimmed and transposed shots or whatever. Ultimately all of the classic films from Hollywood after about 1925 were forged on the Moviola. It felt like blacksmithing in comparison to what we do digitally. And obviously you are physically cutting the film.

When Dan was syncing the film up, there was a sound recordist on the shoot, who was a young film student – maybe 24 years old. At the end of one session, he asked Dan confidentially, “Did you do this on every film?” [laugh] It was just incomprehensible to him that we had to do all this very physical work.

John Gregory Dunne wrote an article around 2004 about film craft. He said, a director friend of his called the old way, which is what we were doing in Moviola, “surgery without anesthetic.” That’s interesting, because how did you do it? Well, first of all, we had to do it. There was no other way. How did Michelangelo carve David? Did he sharpen his chisels after every ten bangs? How many assistants did he have? Just those really ephemeral things that were necessary to do well, which I don’t think we have any record of. So that was another reason to do the film. It was just to say, this is what you had to do.

___________________________________________

Her Name Was Moviola is a crowdfunded documentary about the historic film editing tool. The IndieGogo campaign has now closed, but you can follow the film’s Twitter account for news about the project.

Watch the campaign video below to get an idea of what the film is all about.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now