The beginning of the photochemical film process came in the form of still photography at the end of the first quarter of the 19th century (around 1826). It would be another fifty years before film began to move (the 1890’s) and another 30 or so years for television to begin its birthing process (1926). All of them were originally brought to you in spectacular monochrome.

We still revere the classic black and white, even though some have tried to retrofit films shot in monochrome to color. I can’t imagine such classics as “Citizen Kane,” “Casablanca,” “Psycho” or “Dr. Strangelove” in anything but black and white. The mood was told by light and shadows. Classic Film Noir dictated black and white – what was happening in the shadows sometimes was just as important as what was happening in the pools of light.

Cinematographers used the light, the lens and the speed and quality of the film stock to “color” their images. Famous among these is Gregg Toland who photographed “Citizen Kane.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ezcj4kAF3w8

Toland thought black and white to be so important that he said in an article for Theater Arts magazine shortly after “Citizen Kane’s” release in 1941, “Color will continue to be improved but will never be a hundred percent successful. Nor will it ever entirely replace black and white film because of the inflexibility of light in color photography and the consequent sacrifice of dramatic contrasts… the low-key, more dramatic use of light seems to me automatically to rule color out in pictures of [non-musical or non-comedic] type.”

Notwithstanding Toland’s prediction, color films evolved to approach a number very close to 100% and every genre has been filmed in color – including film noir. Toland was only speaking from the viewpoint of his own creativity. As the motion picture business grew, the decision to shoot color would also become a business decision.

The search for a way to expand the palette first on film and later on video began as soon as many creators found, unlike Toland, working only in black and white too restrictive for them. For those filmmakers, their first attempts at color were crude and had very little to do with photography.

Undaunted filmmakers, anxious to attract audiences with something different began tinting the film, a process of soaking the film in dye and staining the emulsion. They would dye their films all sorts of colors usually to reflect a mood they were trying to convey. Blue was very popular. Early film stock exposure indexes were too low to be used at night. So night scenes shot during the day would be dyed blue and passed off as night, thus beginning day for night photography.

Then there was the laborious process of hand coloring each frame of film to colorize it. The first effort was “Annabelle Serpentine Dance” (1895) from Edison’s studios made for his Kinetoscope, little projection machines designed for an audience of one. Amazingly, it has survived and can be watched right here.

https://youtu.be/BpKani8fags

Several classic films over the years in black and white were handcolored. Two famous examples are Georges Méliès’ “A Trip to the Moon” (1902) and Edison’s “The Great Train Robbery” (1903).

https://youtu.be/mepWfJRIQHY

Méliès’ film was long thought to only exist in black and white. In 1999, Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange of the French film company Lobster Films learned of the existence of a hand colored version. The nitrate print however was thought to be totally unsalvageable as it apparently had decomposed into a rigid mass. Laboratories specializing in restoration didn’t want to touch it.

Undaunted, Bromberg and Lange took it upon themselves to at least try. As they set to work they discovered only the edges had decomposed and they put the process in motion to restore the hand colored film. Over a decade later their work was completed and a digitally restored “A Trip to the Moon” became the opening night highlight of the 2011 Cannes Film Festival.

https://youtu.be/s5x_M_vcNVY

In 1905, The French production company Pathé began using pantographs to make stencils cut into each frame of a film and could handle up to six colors. After a stencil had been made for each color for the whole film, the film was put through a staining machine for each color represented by a separate stencil.

Even though dyeing, hand painting and stenciling were overtaken by advances in photographic processes, they continued to be used for years after one would think they would have been abandoned.

All of the color work up to this point was added after photography and processing. Many times the coloring of a film was inaccurate or completely arbitrary. For example, the hand painting of Méliès “A Trip to the Moon” was the work of a studio run by Elisabeth Thuillier in Paris. She directed two hundred artists painting directly onto the film stock with brushes using colors Thuillier herself chose. While the films satisfied the audience’s thirst for color they were without the natural hues of the scene (color photography versus colored film).

Thanks to a recent discovery at Britain’s National Media Museum, the earliest color motion picture film to capture color as the film is photographed is now placed at 1901 to 1902, long before Technicolor (1916) or the work of George Eastman and his lenticular process (1928).

https://youtu.be/XekGVQM33ao

That earliest film was the work of Edward Raymond Turner. Turner’s work was cut short when he passed away suddenly while still working on perfecting the projection side of his invention. Others picked up where Turner left off and his system evolved into the British Kinemacolor process.

The basics of the system involved exposing two frames of monochrome film one after the other on the same strip of film, one through a red filter and the other through a green filter. After it was developed, the film would be projected using a special projector with two apertures and two lenses, one with a red filter and the other with a green filter.

By doubling both the camera speed and the projector speed, persistence of vision would blend the two colors together and appear to the eye as a color image. This is known as an additive color process as it takes two colors and adds them together on the screen (The presence of the third primary color, blue in equal portions with the red and the green produce white light).

The Turner and Kinemacolor methods created an imperfect system. While Kinemacolor lasted until 1914, it was never a financial success. This was partly due to the expenses involved in equipping theaters with special projection equipment before a Kinemacolor film could be shown.

On a side note, a notable color entry in the still photography market was Autochrome from the French Lumiére Brothers. They would seem to be the first to combine all the color information on the carrier during exposure of the negative. It, too, was an additive color process. The patent on the system was dated 1903 but not marketed until 1907. It is said it was the principal color photography process in use until the advent of subtractive color in the mid-1930’s. However, even though the Lumiére Brothers were involved with cinema, there is no record they ever attempted to develop an Autochrome motion picture film.

https://eastman.org/technicolor/company/herbert-t-kalmus

In 1914, U.S. based Technicolor was founded in Boston, Massachusetts, by Dr. Herbert Kalmus, Daniel Comstock and Burton Wescott. The first Technicolor attempt was virtually identical to the Kinemacolor process with an exception. Rather than exposing succeeding frames alternating between green and red as the Kinemacolor system, Technicolor exposed the two frames at the same time. Unfortunately, they had practically the same results. All the systems suffered from the need to constantly adjust the two (red and green) prisms to maintain alignment of the colors. It’s no wonder Turner was having problems getting his projection system to work!

The results were so disappointing for Technicolor only one film, “The Gulf Between (1917),” was produced using this process. Technicolor pulled it out of circulation and went back to the drawing board.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Gulf_Between_(1917_film)

It took five years but Technicolor tried again in 1922 with “The Toll of the Sea,” the first general release film entirely shot under the Technicolor banner. They used essentially the same photography process but this time the company concentrated on the printing of the film.

From the camera negative, the red and green frames were separated onto their own film rolls. This yielded a green separation and a red separation. The green separation was dyed red and the red separation was dyed green. By printing on film half as thick as normal film and lining up the two dyed separations carrier side to carrier side using a special solvent that adhered the two pieces of film together (the resulting film had emulsion on both sides), colors were subtracted from the print rather than added together as was done through the prisms (In the subtractive process, the primary colors are cyan, magenta and yellow. The presence of all three in proper ratio produces black). Prints from the new system could now be projected on any existing projector and required no modifications.

https://youtu.be/Y6rjFuHYZWA

A note about the “two strip” process as the red/green subtractive Technicolor process came to be known. While it ignored blue, the third primary additive color, it rendered skin tones accurately. Through careful photography that kept the need to reproduce blues to a minimum, acceptable results were obtained.

https://youtu.be/8iy_MjegGWY

Sequences of major silent films such as “The Ten Commandments” (1923), “The Phantom of the Opera” (1925) and “Ben-Hur” (1925) were shot using the red/green process. But the two strip adhesive system still presented technical problems mostly due to the heating and cooling of the print as it ran past the hot arc lamps of film projectors. They were also prone to scratching due to the presence of the emulsion on both sides of the print. This two strip scheme became a stop gap. Technicolor was already hard at work on an improved process.

In 1926, Technicolor introduced their version of the dye transfer process that eliminated the sandwiching of the two strips of film. Dye transferring for still photography had been around since the turn of the century. And it had been used before in motion picture films. Cecil B DeMille first used it in his film “Joan the Woman” about the life of Joan of Arc in 1916. However, it was not used in the photography of the film but in coloring it as previous films had done with tinting.

https://youtu.be/g9S76vtk4Ro

The first film to use the new Technicolor version of the process was “The Viking” in 1928. It continued to use the same cameras and red/green breakdown of colors as the previous system. However, the physical marriage of two dyed prints that had caused so much trouble in projection booths was gone. It was replaced with a single piece of film that was stable and also able to accommodate optical soundtracks that were allowing movies to speak for the first time.

Luck was on the side of Technicolor when the world suffered financial calamity with the onset of the Great Depression. As studios began to abandon plans to shoot films in the two color system to save money, Herbert Kalmus was completing plans to once again bring the studios and the audiences back to color.

Kalmus had commissioned the building of a new Technicolor camera and a modification of the dye transfer system. Both would accommodate three strips of film allowing red, green and now blue separation negatives. The camera would photograph three strips in the three primary light colors (red, green and blue) while the subtractive dye transfer process would allow all three complementary colors (cyan, magenta and yellow) to be placed on one strip of film.

https://youtu.be/N-T8MVrw1L0

The first producer into the three strip color market was Walt Disney. In 1932, Kalmus approached Disney with the offer to use the new three-color process for the first time. Disney jumped at the opportunity. He even scrapped a film that was currently in production in black and white and started over using the three strip color camera. “Flowers and Trees,” one of Disney’s Silly Symphonies series, while not the first animated film to be shot in some form of color, was a sensation with audiences and critics and won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Subject that year. Disney negotiated an exclusive contract with Technicolor and all subsequent Silly Symphony cartoons were shot in the Technicolor three strip process as well as the first animated feature “Snow White” (1937).

https://youtu.be/NOk7uIZeAwQ

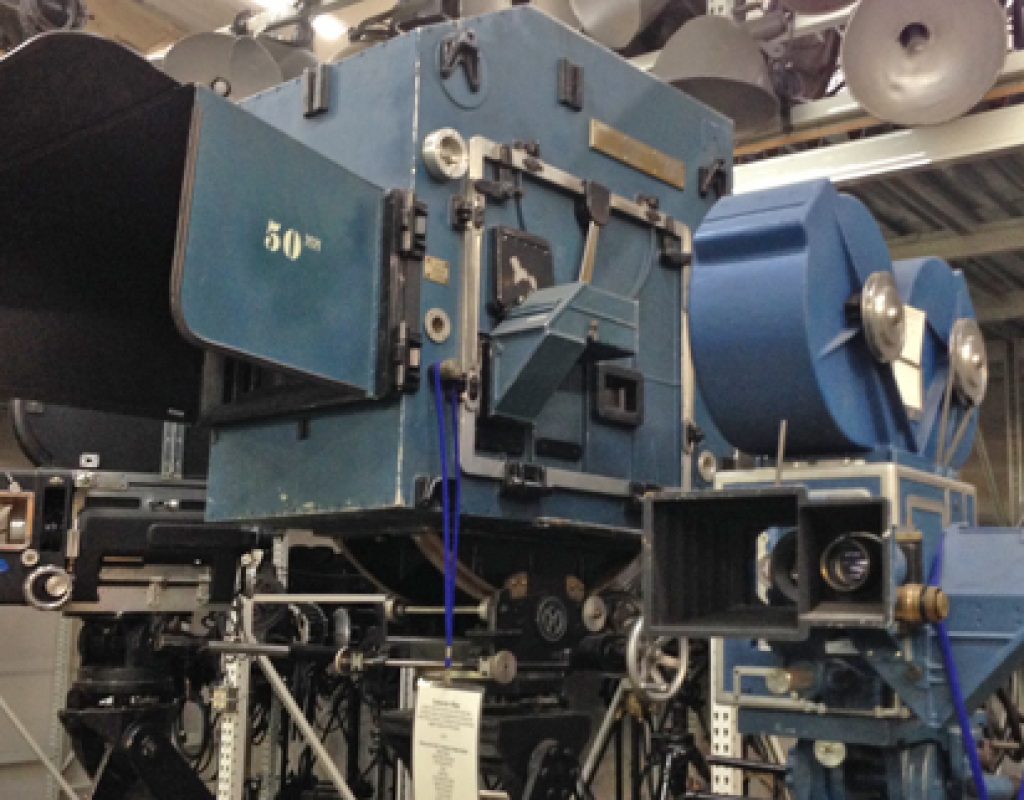

Technicolor remained the gold standard for color motion pictures into the 1950’s. A producer who contracted with Technicolor meant they would provide the camera (an especially cumbersome piece of equipment), specially trained crews to operate it, all film stock and processing and an expensive finishing process. It was an expensive system that was finally overcome by companies like Eastman Kodak who in 1950 introduced its first motion picture negative film that allowed producers and studios to use the same cameras they had been using to shoot black and white films as well as their own crews and processing plants.

But Technicolor’s three strip and dye transfer process couldn’t be matched and continued until 1954. As history has shown, Technicolor’s films are very stable and films produced in the process maintain their vivid colors even today. The simpler emulsion layer based systems such as Eastmancolor were prone to color fading and it’s very difficult if not impossible in many cases to revive them to their original luster even using today’s digital tools. In the end, the cost advantage of the simpler technology finally overcame Technicolor and the final three strip production, “Foxfire,” was shot in 1954 by Universal Pictures.

The dye transfer process yielded such superior quality prints, Technicolor was able to adapt it to convert single strip color emulsions, such as Eastmancolor, and continued it until the early 1970’s. Ultimately, it also became too expensive not only in monetary costs but in time. With the number of screens increasing in the mid-1960’s, producers needed more prints faster and in more locations. One of the last American films printed in Technicolor’s process was the second “Godfather” film in 1974 although it revived briefly in the late 1990’s with a shorter time frame. The first film to use the revived version was Warner Brothers’ “Batman and Robin.” Later it was used for new dye transfer reissues of “Wizard of Oz,” “Gone with the Wind,” “Apocalypse Now Redux” and others until it was discontinued right after the company was sold to Thomson Multimedia S.A. in 2001. Little can be found about the revived process as there was scant publicity on it.

Today, digital has made film photography and printing obsolete. That can be a good thing or a bad thing depending on who you talk to. As you can see throughout the article, an upside is that digital can save some of the defining moments of earliest years of the medium. But whether they are black and white or color, they have to be in a restorable condition. Hopefully the discovery of of treasures such as Méliès’ handcolored version of “A Trip to the Moon” will continue to turn up.

As for color, once something expensive for use only in special productions, it has evolved to become another creative tool in a filmmaker’s bag of tricks. One can only wonder what Greg Toland would think of how color has evolved be used in ways that were unheard of when he was advocating for black and white photography.

Next time, we’ll concentrate on how video managed to rise from blurry washed out color images to overtake and merge with film as the single source of imaging in the modern day and render 100 years of film obsolete in less than a decade.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now