An article at Adobe Spark says the film industry is spiraling into obscurity. Do you agree? I encourage you to read it and then come back so we can chat further.

Read it? Good. Well, that was cheerful. Not entirely inaccurate, but not completely accurate either. Mr. Harrington brings up a number of points that I worry about, and some other points that I don’t think are as serious as he thinks they are.

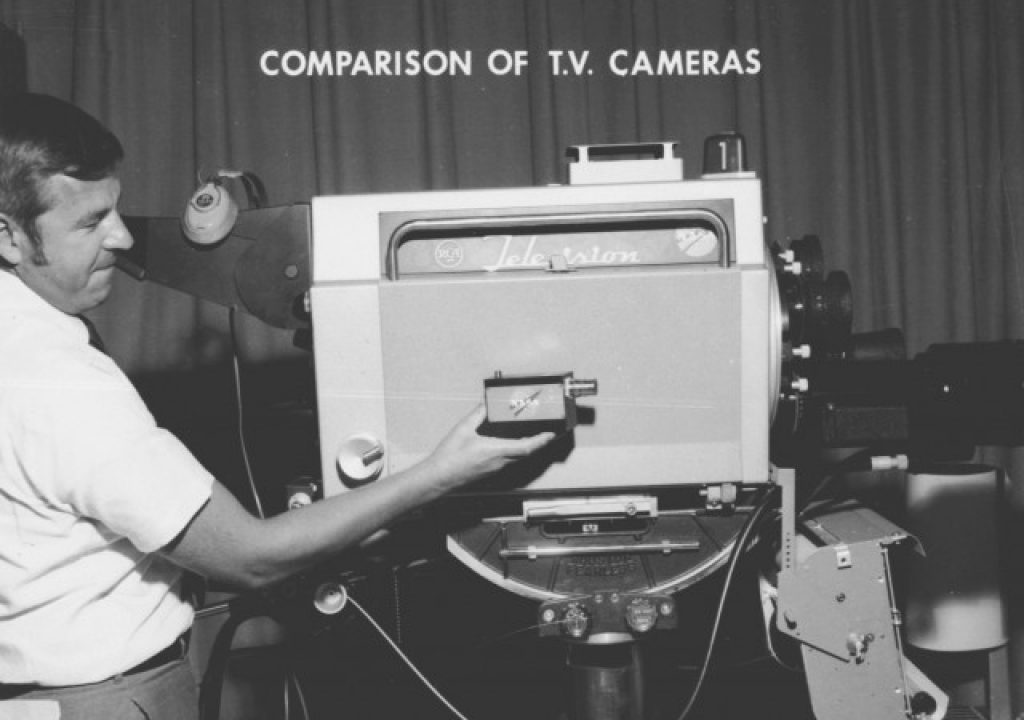

I do think this industry is going through some very severe changes at the moment. I don’t know exactly what they are, or what the industry will look like when we come out the other side, but the availability of cheap cameras that make “good enough” images is devaluing the contributions of media professionals.

What’s worse is that the need breed of media professionals—the ones who are buying the cameras, and those that are hiring them—don’t yet have the sophistication to understand what they are missing.

To a great extent this started with DSLRs that shoot video. A few years ago the Associated Press went to Canon and said, “Hey, we don’t want to send both video crews and still photographers to the same events. We’d rather send a still photographer and have them shoot some video. Can you hack your still cameras so they shoot rudimentary video? And can you make them fully automatic so they don’t scare off the photographers who aren’t comfortable shooting video?”

Canon did this, and the Canon 5D took off like a rocket. It makes images that look good enough(tm) to the untrained eye, and the camera itself is quite affordable. Where RED promised owners that they could make Hollywood-quality movies for $17,000 (in this case, “quality” equated to “resolution”), Canon offered an even cheaper option. They didn’t promise that camera ownership would lead to spectacular success, but RED had already taken care of that.

GoPro makes cameras that require virtually no artistic intervention. They make very pretty pictures, mostly because the user can attach them in places from which we haven’t taken pictures before. You wouldn’t shoot a feature film with one because it lacks the kind of artistic control one needs to tell an intentional story… oh wait, Hardcore Henry was shot on GoPros. (Of course, it also looks it. And, for what it is, GoPros did a fine job.)

The fact that nearly anyone can buy a camera, and nearly anyone can make decent pictures with it thanks to advanced imaging technologies, is devaluing what we do to some extent. I see more and more kids shooting spots (where I make my income) using that floaty-DSLR-natural light-documentary style that’s become so popular, but that’s the only style they know how to do and eventually it will go out of style. (That style came about directly as a result of DSLRs that shoot video, as the 5D’s small size and low weight facilitate shooting while trying to find a shot.)

Others are shooting more traditional spots but don’t seem to have a solid grasp of lighting for mood and content as the technology they’ve grown up with can capture adequate images under natural light and spiff them up using cheap color correction tools, so they’ve not learned how to aggressively and efficiently shape natural and artificial light.

A while back, fellow PVC contributor Adam Wilt sent me a cartoon that sums up the situation perfectly. In it, one person says to another, “Your camera takes pretty pictures.” The other person responds, “Your mouth says nice things.” You can leave a camera in a room for a day and, when you check the cards for images, you won’t find any. The camera doesn’t make images on its own. It’s just a tool. It’s a bit like telling a painter, “Your painting is beautiful. You must have very nice brushes.”

The proliferation of cheap imaging devices and editing tools is devaluing what we do as media professionals, in the same way that Photoshop devalued graphic design and the Internet has devalued writing. There will still be ways to make money, but I think that over time fewer people will be making real money doing what we do now. There’s going to be a glut of media out there, and most of it will be good enough, or entertaining enough, to replace professionally created content.

At the same time, though, I see some hope. Commercial advertising is losing its power due to oversaturation, and the advertising industry doesn’t seem to realize this. YouTube allows me to skip most commercials after five seconds if they don’t appeal to me, and I’ve yet to see anyone make a YouTube-specific commercial that recognizes this by incorporating a powerful hook within that first five seconds. I’m also fascinated that many YouTube commercials are :30 seconds to two minutes or more in length, when the point of YouTube is to put interesting content in front of you right now, and the only way advertisers seem to know how to reach viewers is to frustrate them by getting in the way for long (by Internet standards) periods of time.

If I were an ad agency I’d go out of my way to make fewer commercials, and shorter commercials, but put the same amount of money into them and kick the creativity up several notches. I’d also be a lot more daring. As “creative” as spots are supposed to be, many are very, very safe bets and don’t take chances. That doesn’t work well on the Internet. Short spots with powerful hooks that push creative boundaries would be very effective in a YouTube world—and also the broadcast world, in which I no longer participate due to the unending commercials, which I love to shoot but hate to watch for 20 minutes every hour—and could revive a dying industry by making advertising content part of the entertainment. Spots could be like a short film in front of a feature film, and—if done well, and if there weren’t too many—people would want to watch them! (This series, produced by BMW, comes to mind.)

That’s not the kind of material that any yokel with a camera can pull off. Consistently powerful storytelling that sells products takes experience and skill to create and produce. That’s going to be more important than ever before, if traditional advertising is to survive. The problem is that I see very little indication that this is on anyone’s radar.

When I grew up, TV was a wasteland of mindless, formulaic and factory-generated entertainment. Now TV series quality eclipses that of feature films to the point where I’m starting to wonder if features are dying as an income-generating and storytelling platform. Many, if not most, of the feature films currently in theaters get terrible reviews. There are very few that I want to see, and most are mindless, formulaic and factory-generated.

I recently saw a film in a theater for the first time in months, and the movie was fine but not great. (It got 90% on RottenTomatoes.com, but that doesn’t seem to mean what it used to.) When I compare that to the experiences I’ve had recently watching TV shows such as Mr. Robot, The Leftovers (possibly the best TV show I’ve ever seen), Daredevil, Jessica Jones, The Man in the High Castle, Fortitude, Broadchurch and Happy Valley… there’s no comparison. Suddenly we have streaming media networks that aren’t afraid to appeal to niche markets with shows that don’t play down to their audiences. They’ve understood that, while the Internet gives people instant gratification over short periods of time, there’s still a market for long-form content that forces the audience to pay attention and to think over long periods of time—as long as that show can deliver a suitable emotional and dramatic reward. Right now there are lots of shows that are doing exactly this. It’s not unusual for viewers to binge watch 10-12 hours of a new TV season in a day or two. Clearly there’s a place for long form storytelling, even in the age of the Internet.

The competition for streaming network television eyeballs has created a renaissance of competition, where the only way to win is to create new, novel, smart and well-produced content.

So yes, at the low end of production, and in advertising, there seems to be a race to the bottom. There are solutions to this but it seems that entire segments of our industry are slow to catch on. At the same time, we’re seeing a renaissance in dramatic entertainment that exists entirely outside the realm of the movie theater. That’s new, and it’s exciting.

In the early 2000s, many corporations mandated that their internal media, and much of their external-facing media, look as if it was shot by my mom. This was coined “The YouTube Look.” The idea was that viewers could relate better to media content if it looked as if they could have shot it themselves. This makes about as much sense as distributing novels or textbooks that are written as poorly as the average person could write them. (If this was viable there would be fewer websites that make fun of the thousands of awful self-published books on Amazon.)

One corporate media department stopped hiring me because my work “looked too good.” A production company that produced YouTube virals dumbed down my work in the color grade because it looked “too professional for Youtube.” Within a few years, though, a number of companies began hiring commercial directors and advertising agency creatives for their internal media departments because they realized that, when you dumb down all your media to make it look like it was made by average people, that reflects on your products and your branding. Why should someone pay attention to your marketing media, or buy your products, if your media branding is (1) nothing special, and (2) looks exactly like everyone else’s? How does that make you, or your product stand above the others? (It doesn’t.)

3D is dead, again. VR seems to be the new 3D, but based on what I’m seeing I don’t know that it’s going to be any more successful than 3D was. I think it’ll be a niche market that has legs, in that it’s going to build a consistent user base who will pay for those experiences and keep it alive, but no one has yet learned how to tell live action stories with VR, and that’s going to reduce its appeal. It’ll be great for gamers and virtual experiences, but beyond that… it’s a medium that most viewers can only tolerate for short periods of time and whose production requires levels of planning, performance and perfection far beyond what most content producers are willing or able to do. Shooting VR excites me, but I’ve not seen anyone figure out the storytelling aspect yet.

HDR is exciting. If manufacturers can make consumer HDR TVs for early adopters that don’t suck (doubtful—edge-lit HDR displays, for example, can’t legitimately be said to create HDR imagery at all) then I think the TV renaissance will continue and strengthen. There’s clearly an audience for thought-provoking intelligent long-form entertainment that has been long ignored, and the streaming media networks aren’t afraid to go after that market. It’s clearly paid off. If that entertainment is lit and shot to take advantage of all that HDR can offer—and it offers quite a lot, between dazzling highlights and a huge P3-like color gamut—then we’re going to see a revolution in in-home visual storytelling.

The Spark article makes a few valid points, but it also makes some strange ones. For example, a Scooby-Doo movie on DVD that costs $4 doesn’t mean that the media is somehow less valuable than the $30 Scooby-Doo toy. The DVD is the advertisement that sells the toy, so it’s incredibly valuable. You wouldn’t want to sell the DVD for $15 or $20 as few parents would spend that much on a silly cartoon for kids, but at $4… the kids won’t want the toys without seeing the film, but once they see it a lot of parents will be shelling out $20-30 for those toys.

What’s more important is that professionals made money working on that movie. It wasn’t made by amateurs. And I think (and hope) that a number of us will continue to make money working in media, for one reason and one reason alone: high quality content still sells products (either other products or itself) better than low or average quality content, and those who can produce high quality content consistently should remain in demand. The question is: for how long will the public notice the difference between high quality and average quality content? And how much more will companies pay for that kind of work, especially when those who commission the work have no media taste? My hope is that constant improvements in image display quality will keep a lot of professionals working. HDR is coming, and it requires some extra tricks and knowledge in order to make it all it can be.

Years ago I shot a wonderful corporate project that showed a typical day in the life of a family who were using a company’s products 30 years in the future. The end client, who had an engineering background, had the director strip out all the dialog and put in subtitles that read like bullet points. They didn’t understand that most communication, especially marketing communication, is best done through storytelling and by building emotional connections with the audience. As engineers, all they understood was that information had to be delivered. They never considered that how it is delivered is equally important, if not more important.

That’s my biggest fear: that those who commission marketing and non-agency advertising work will be fooled by the cost of equipment, and its perceived ease of use, into thinking that generating moving PowerPoint presentations are all that are necessary. Nothing could be farther from the truth, although it may take an extended period of time before that becomes obvious.

If I were to look at the feature film and advertising industries alone, with an eye to YouTube content and other cheap media distribution platforms, I’d be worried. The quality of television, though, tells me there’s hope. Not everything on TV is high art, but there’s certainly more of it than ever before, and it’s clear there’s demand for it.

There will always be more of a market for Ikea furniture than Stickley, but Stickley has survived for a hundred years and they’re still doing quite well. My hope is that, as things settle out, those who are serious about making money will realize that it’s important to spend money to do so—and when they do so, they should go with professionals who consistently make exceptional products that give them the most bang for their buck.

Click here to read what other PVC authors have to say about this article.