20 years ago this week I answered the phone – and this is what I learned.

Recently, Richard Harrington published an article titled “Why film and video have lost their value, and what this means for innovation”. It’s a thought provoking post that’s prompted much discussion amongst the ProVideo Coalition authors. I don’t have any comments to add in direct relation to Richard’s piece, but it does introduce the general issue of creativity and value.

In my own way, I first considered the relationship between creativity and value just after I left university, when a lengthy phone call changed the way I understood television and advertising. Both industries (TV and advertising) have changed a lot in the twenty years since then, and with Richard’s piece as motivation I thought I’d share the insights I learned from that phone conversation in June, 1996. I don’t remember the conversation word-for-word, but this article serves as a general outline of everything we covered.

Let’s begin by setting the scene – it’s Australia, a long time ago when I had more hair and less of an idea about everything. If you’re younger than I am then you might find it difficult to imagine a world where the internet was brand new but mostly text, where there was no such thing as Netflix, and you could count the number of TV channels on one hand. But such a world did exist, and I grew up there.

The Golden Age – or whatever

Lots of things are described as a ‘golden age’ but there’s rarely any definition of when the golden age began or ended. Within the Australian television industry you often hear nostalgic references to the “golden age of television”, but there’s no consensus on when that actually was. It’s just this general term used by old people when they start reminiscing about how things were better before you started working with them.

Woody Allen even made a film on this very topic (Midnight in Paris), where the characters keep travelling further back in time, and at each stop they encounter people reminiscing about the ‘golden age’ before them – only to travel there and discover it’s not that golden after all.

I’m going to take a pretty good guess, though, and suggest that the “golden age of television” in Australia was the period before the internet, and before cable TV arrived, and so there was nothing else to watch. It’s when the only television there was, was what we now call ‘free-to-air’. If you worked in the television industry then things would have looked pretty rosy – golden, even – because the entire nation watched whatever you put in front of them, because they didn’t have any other choice.

From before I was born up until after I graduated, Australia only had three commercial TV stations. There was also the government funded ABC and another channel devoted to foreign language content – but if you asked the general public they’d agree there was never anything good on them. So to everyone growing up in Australia, watching something on TV meant choosing one of the three main channels to watch.

With no internet and no cable / subscription TV services, everyone watched TV because that’s all we had. With hardly any competition, popular shows in the 1980s could have huge weekly audiences with ratings figures unheard of today. One particular Australian sitcom (“Hey Dad”, the anathema to any aspiring comedy writer) regularly won 40% of the total audience on a normal Wednesday night – a figure unheard of today. So for some time, the highest rating TV program in the country was a locally made sitcom – even though it wasn’t really very good. But for those of us aspiring to work in the industry it gave us hope – if ‘Hey Dad’ could rate over 40 on a weeknight, imagine if the networks had something that was actually really good!

Everyone watched TV. As someone who grew up in the 80s those three channels of commercial TV were the primary form of entertainment we had. I don’t dispute anyone who worked in the television industry calling it a ‘golden age’ – because I’m sure it was. We didn’t have a choice.

The undergraduate years

As a teenager I always knew that I wanted to work in the film & television industry, even if I wasn’t sure which aspect of the industry I’d end up in. Back then I didn’t know visual fx compositing even existed, and for a while I thought I wanted to direct TV commercials. But although I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do, I knew it involved video production.

I don’t know anyone who studied film and television production by accident. Especially during the early 1990s when I started my university course, TV production was a niche interest. Even in a large metropolitan city like Melbourne, there were only a few courses that had any sort of film or television focus.

There isn’t anyone around whose parents sat them down for a talk and said “Hey son, your mother and I are a bit worried about your dreams of becoming an accountant. We’re just not sure there’s a future in it. We think you should become a TV commercials director in case the accountancy thing doesn’t work out, then you’ll have something to fall back on.”

This meant that those of us who did enroll in film / tv courses had made a special effort to do so, and had similar interests and ambitions. We’d all chosen to study something we were genuinely interested in and passionate about so – broadly speaking – we shared a lot in common. Because film and video productions involved lots of people, there was a genuine sense of community and camaraderie amongst us, as everyone helped out on everyone else’s’ projects. You might be a boom swinger one day, a camera assistant the next, and maybe even the caterer the week after that. Student productions could range from narrative dramas to documentaries, to sketch comedies, experiment art pieces, music videos and so on. Just being part of a shoot was fun and exciting. We shared a passion for creating something, and being part of a team that created something together was reward enough.

Our student productions were generally crewed by each other – everyone was a volunteer – but outside of our class there were only ever a few degrees of separation between everyone else in Melbourne who wanted to make films. It wasn’t uncommon to hear about someone needing people for a crew, and then to turn up to the shoot and not recognize anyone else there. But then you’d discover half the other people there didn’t know anyone else either, and roles would be handed out and everyone would work together with the sort of excited enthusiasm often found on student crews. Even now, roughly 20 years after I graduated, I’m sometimes reminded of a short film, music video, or some other production that I helped out on, even if it was only for a few hours.

A friend of mine from university has often reminded me of one particular example. Somehow he’d heard about someone making a short film and had volunteered to help, and he talked me into coming along as well. It was being shot at night – I didn’t know the guy making the film, or anyone else involved – but that wasn’t unusual. So I found myself driving for about 2 hours to get to the location at midnight, which was a dirty public toilet next to a shipping container yard. It was incredibly cold and noisy. I said to my friend “It’s 2am and I’m freezing half to death lugging c-stands and cables around a dirty public toilet for a bunch of people I’ve never met before. For free. But I can’t think of anything else I’d rather be doing!” He thought that was funny, and still reminds me of it now and again.

I was lucky enough to have found something that I enjoyed doing, and I didn’t stop to think about what life would be like after university. Looking back now, I can see that while I didn’t have any conscious expectations of what working professionally would be like, I had simply assumed it would be pretty much the same as being a student.

Bachelor’s degree in naiveté

When I finished my university course I had a more focused idea of what I wanted to do – and that was to write and direct my own sitcom. The problem was that I didn’t know how to go about it, but I wrote a few scripts and posted them to the local TV stations. My options were limited, but at least it meant I only had to pay postage on four copies of my script – the three commercial stations and the ABC.

I honestly don’t remember what I expected to happen. Obviously I hoped to have my sitcom made and broadcast on television, but I had no idea of the process that would involve. I think I was hoping for an expression of interest, so I could offer to make a pilot by calling up my old classmates and putting something together just like another student film. The only sets I’d ever been on were student productions, crewed by enthusiastic friends and colleagues, and I assumed that if someone gave me the go-ahead I’d be able to make a sitcom the same way. It’s over twenty years ago now, so I’m not really sure, but I probably had this notion that one of the TV stations would post out a cheque and leave to me to it, and then I would go off and make the show with my friends, and then I’d drop a tape off to them when I’d finished it. It mightn’t sound realistic now, but I had no experience to suggest it would be any different.

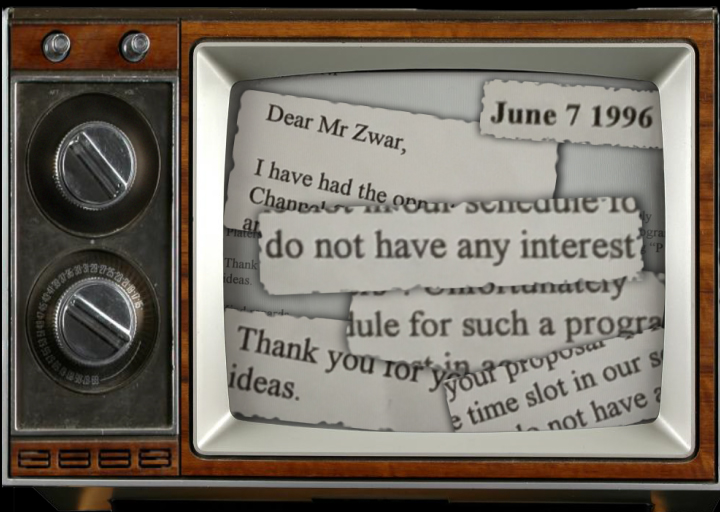

So while I didn’t know what to expect, I was pleasantly surprised when the phone rang a few weeks later and it was someone from one of those TV stations. He began by telling me he liked my script, and that’s why he’d called me personally. Then he said they weren’t interested in making it, and that he doubted any of the other TV stations would be interested either (he was right). But despite the rejection he wanted to talk to me about why it wouldn’t get made, and to offer some insight into how television really works.

At the time I had no idea who the guy was, or what it meant to be a national director of programming, but I later learned he was the 2nd or 3rd in command of the entire network. It was many more years before I really acknowledged just how important he was, how fortunate I was to receive that call, and how generous he was to spend so much time talking to me – a young unemployed graduate.

I don’t remember everything he said, although I know we talked for over half an hour. But I do remember the general course of the conversation, and how he opened my eyes to a side of the television broadcast industry I’d never considered before. As it turns out, there’s a big difference between a bunch of students making a short film and a TV station making a show for broadcast.

Behind the scenes, really.

Why do TV stations exist? Why does television exist? Although I’d always known that I wanted to work in film and television production, I’d never stopped to think about why film & television existed in the first place. Although I wanted to write and direct a TV show, I hadn’t thought too much about why anyone else would want to pay me to do it. After all, everyone watched TV, so what was so unusual about wanting to make TV?

As a student I was surrounded by like-minded friends who shared the same interests. We’d chosen to study film and television because it was something we were passionate about. It’s difficult to articulate the exact nature of the urge to make films and tell stories – but it’s definitely some type of artistic calling.

Except TV stations aren’t full of artists. They’re not run by patrons. They don’t hand out cheques to people who want to write and direct their own short films for fun. It would be nice if they did, but they don’t. The television industry is exactly that – an industry.

Here’s the harsh reality. In a general sense, TV networks exist for one reason – to get people to watch TV ads. While it might sound simplistic, TV networks can be described with a basic business model. (just a reminder that this is from 1996, before cable, before the internet and so on…)

Like most businesses, there’s an initial outlay: in order to broadcast TV, a TV station needs to buy a license from the government. Then there’s the cost of the equipment needed to set up studios and broadcast the pictures. Finally, they need some TV shows – whether they’re buying shows that are already made, or paying people to make new ones.

Setting up a TV station and broadcasting programs to the general public for free is not an altruistic cultural endeavor. Like any business, a TV station expects to make money back, and to do this they also broadcast TV ads. It’s pretty simple – businesses pay the TV stations to broadcast their ads, and the TV stations get the general public to watch those ads by mixing them up with shows that people want to watch. If a TV show is popular and has a large audience, then the TV stations can charge more money for the ads they show during the program.

Television ads are the cultural equivalent of a cuckoos egg.

In the earlier days of television it was common for businesses to sponsor and pay for an entire TV program. We still use the term ‘soap opera’ to denote the types of daytime dramas that were originally sponsored by soap manufacturer Proctor & Gamble. Proctor & Gamble have sponsored over 20 soap operas since they started the genre on radio during the 1930s, and they still sponsor ‘The young and the restless” today.

Averaged out over time, TV stations have to make enough money from showing tv ads to cover the cost of everything else – the broadcast license, the equipment, and the cost of the programs they show. So when you hear about the cast members of a popular show receiving $1 million per episode, you can guess that the networks broadcasting the show are making more than enough from advertising to cover their costs.

Paying networks to broadcast TV ads has always been expensive, and a simple Google search reveals some staggering numbers. Perhaps the most lucrative advertising spot in the entire world is during the USA Super Bowl, with a single 30-second ad costing over $4.5 million dollars. While the Super Bowl may be an annual event, popular TV shows can command over $400,000 per advertisement every week. The sums of money are extraordinary.

It’s not a blank cheque, however, and there are limits to how many ads the public will tolerate. Depending on which country you live in, TV stations are restricted to a certain amount of advertising each hour – and these quotas have changed over time. Within the television industry the term ‘broadcast hour’ is sometimes used to denote the duration of a show without advertisements. During the 1960’s a broadcast hour was 51 minutes – so a TV show that was scheduled to run from 8pm to 9pm was actually only 51 minutes in duration. The remaining 9 minutes would be taken up by TV advertisements. Today, a broadcast hour in the USA is only 42 minutes, and here in Australia TV stations can also broadcast up to 18 minutes of ads within a 1 hour period. If you include opening titles and end credits, a “one hour” tv show may only require 40 minutes of actual production.

It’s economy, not creativity

The reality is that broadcast TV does not exist for any cultural or artistic reason. Free TV exists to broadcast TV ads. There is no obligation for the networks to make shows that are high quality, or even highly regarded. All they really need to do is attract an audience to watch the TV ads that pay for all of it. If that means making shows like ‘Baywatch Nights’ then they will.

There are many writer’s anecdotes about being asked to add a teenager to their show ‘to appeal to the youth audience’, or introduce a character’s grandmother ‘ to appeal to older people’ and so on. The Holy Grail of television programming is a show that is watched by everyone, appeals to all demographics, and is cheap to produce.

The biggest fear the TV networks have is that someone might complain about a show they don’t like directly to one of the companies that advertises with them. For this reason, TV networks tend to avoid shows that might be considered risqué or controversial. Even a single complaint letter can have enourmous repercussions. The worst-case scenario is having the public threaten a boycott of a company’s products because their ad was shown during a TV show someone didn’t like. This is why shows like ‘Southpark’ will never be seen on free-to-air commercial TV. Thinking about possible letters of complaint is what keeps the TV network execs awake at night.

In my particular case, this was the specific reason why the commercial TV networks rejected my sitcom – its undergraduate humor had the potential to ruffle the feathers of the general public, which in turn could cause a backlash against any business whose ad was shown in the ad breaks. Sure, it might appeal to a few university students – but it might also offend some other people enough that they might write letters. And that would be a disaster. No-one would want their ads broadcast during the show. And if the networks couldn’t show any ads during the show, then there wasn’t any reason for them to make the show.

So they didn’t make the show.

TV Networks want shows that appeal to everyone without offending anyone, and they want them to rate well. A show may be critically acclaimed and highly regarded, but if it doesn’t rate then it will soon be cancelled. TV stations aren’t going to pay for a production just because it gets good reviews – they need an audience to watch their TV ads and advertisers to pay for them.

A less common scenario is when a show rates well but doesn’t attract sponsors – businesses are selective with the types of TV program they want to be associated with, and there are many shows out there that might be considered too risqué for a corporate image. In Australia this happened with a long-running variety show called “Hey Hey it’s Saturday”. It had run for 27 years and still rated highly, but the format was dated and many advertisers didn’t want to be associated with its politically incorrect image. So even though the show had a large audience (very large by today’s standards) the image it presented was deterring sponsors, hence it was a problem for the TV network, and eventually it was cancelled.

At the time I was attempting to write a sitcom I collected magazine and newspaper articles I thought were relevant. They’re a bit ragged now but still interesting reading – especially with the benefit of hindsight. One of them mentions how the economics of running a TV station resulted in another popular Australian TV show being cancelled after 21 years on air.

In 1980 a new game show called “Sale of the century” was launched on Australian TV. It proved incredibly popular and was shown five nights a week until it was cancelled in 2001 – becoming the longest running game show in Australian television history. (I even auditioned for it during the early 90s but didn’t make the cut) After 21 years on air, “Sale of the century” was not cancelled because it was no longer popular, or because the ratings had dropped. It still regularly won its evening prime time slot. It was cancelled because someone at the network had done some basic maths. The article (this is from about 2001) suggested that each episode of Sale of the Century cost the network roughly $100,000 to make. Alternatively, they could buy episodes of the US sitcom Frasier for about $5,000 each. Despite 21 years of successful broadcasts, they decided to go with Frasier. The interesting thing was that the ratings for that time slot hardly changed. The public were disappointed that Sale of the century had gone, but they just watched Frasier instead. So the TV station still had the same viewers, and presumably the same advertising revenue, but for 1/20th of the outlay. It wasn’t long before the other TV networks realized they were onto something, and soon episodes of The Simpsons were being shown 5 times a week as well.

Frasier was like the coal miner’s canary for the TV networks. Cancelling a locally made show and replacing it with a cheaper import didn’t cause the TV station to collapse overnight. In fact it worked out rather well for everyone, except those involved with the production of ‘Sale of the century’. The canary hadn’t died – it had lead to a whole new direction.

A TV station is not like a university film and television course. The people who make the programming decisions don’t turn up to work wearing black turtleneck sweaters and spend the mornings discussing the arthouse film they saw last night. When a TV station decides to commission a show it’s not because they think it will be fun. All programming decisions are based on calculations relating to audience demographics and potential advertising revenue.

If you’re making, who’s buying?

If you’re trying to sell a TV program to a free-to-air network, you need to have a very clear pitch that includes exactly who the audience is, why they will want to watch the show, and when they will want to watch it. You also need to have a good idea of what the show’s basic themes and image are, and what type of businesses will want their ads shown when it airs.

In my case, I hadn’t considered any of these things. If I had been asked in 1996, I might come up with the following:

Who is the audience: my friends

Why will they watch it: it’s funnier than ‘Hey Dad’

When will they watch it: whenever it’s on TV…

What business will want their ads shown during it: Huh?

TV timeslot tetris

TV stations plan their broadcasts months in advance – running a TV station is not like being in a band where the playlist may change every night and you can take requests from the audience. With broadcast TV every minute is accounted for, with timeslots allocated to different demographics and program types.

With our local TV stations some timeslots have remained the same ever since television began broadcasting over 50 years ago- 5:30pm has always been a game show, 6pm has always been the news, and 7pm has always been the evening current affairs show. The shows themselves may change and evolve, but the basic timeslots haven’t.

Other timeslots have evolved and changed as the public’s viewing habits have evolved over time – decades ago Friday nights were reserved for the premier movie of the week, before drifting to Sunday nights instead. Then the advent of reality TV shows such as Big Brother heralded another huge shift in TV programming, with new episodes being shown every evening – 4 or 5 nights a week. These days movies have disappeared from prime-time TV altogether, having been replaced by the weekly special extended over-hyped edition of whatever cooking / renovation / reality dating show is in the headlines.

While the public’s taste in TV shows has changed and evolved, the basic approach TV stations have to evaluating new programs has stayed the same. If you pitch an idea to a TV network their first considerations are what timeslot the show could potentially be shown in, and for what audience demographic. If the timeslot most suitable for the show is already taken then there’s little incentive for them to consider an alternative.

All of this is before you consider the internal divisions within large networks, and the timeslots allocated to different departments. A TV station may be divided into three major divisions – news, sport and entertainment. Within each of these divisions will be more departments. The overall news division may have different departments for breakfast, evening news and weekly current affairs. The entertainment division may have separate departments for childrens TV, game shows, drama, comedy and so on. Every TV network will be structured differently, but they will all have a number of departments who have individual timeslots and audience demographics assigned to them.

This means that despite a TV station broadcasting 24 hours a day, 7 days a week they may only have one timeslot allocated to new episodes of a half-hour weekly sitcom. If they have already have a sitcom on air, then there’s simply no timeslot available for another one – even if the writer claims it is better than the one they already have. And if the one they already have is rating well, then why consider an alternative? There’s even a local story about Kerry Packer (owner of Channel 9 in Australia) buying the rights to an overseas show – not because he planned to broadcast it, but simply so it wasn’t bought by one of the other two stations.

If you’re pitching a comedy show and suggest to them that 8pm on a Wednesday night would be a good time, but that timeslot has been allocated to a different department (such as sport) then they won’t be interested. But if you suggest 8pm on a Monday night, and that timeslot has been allocated to the comedy department, then you’ll have a better chance of success.

Sometimes cunning Producers can work their way around network politics to their own advantage. A TV network may not be interested in a new weekly drama series – but they may have an opening for a one-off mini series. So just condense and re-write the script so the drama series you had in mind is now a mini-series, and if it rates well then it may become a drama series next year.

Another example is the source of my undergraduate inspiration: the BBC series The Young Ones. This infamous British sitcom broke all of the rules when it was first broadcast in 1982, and was renown for its anarchic comedy.

One of its defining features was the weekly inclusion of a musical act – roughly half-way through the show the actors would stop, a band would appear and perform a song, and after the song finished the show would resume. This is not something you see in any other sitcom. Many ascribed this quirky trait as just another example of young, zany comedy – but in reality it was rooted in BBC politics. ‘The Young Ones” is generally referred to as a sitcom, but sitcoms were funded by the comedy department, and the budgets allocated to sitcoms were too small for the unconventional scripts. One way for them to obtain the necessary budget was to go through a different department and be classified as a variety show – but in order to be classified as a variety show, they had to include a live act. So they did, and British sitcoms were never the same again. So technically, my favorite sitcom isn’t actually a sitcom – it’s a variety show.

ill also appeal to a particular demographic, eg family entertainment, teenagers, and so on. Particular audience demographics may be more desirable to specific advertisers, so the size of a television audience may not directly relate to the cost of the advertising spots during the show. At the same time, a TV network will have multiple divisions, departments and sub-divisions- each with their own timeslots allocated to them, and an expected demographic.

Fitting all of these pieces together is a complex and constantly evolving puzzle, but one you must understand if you want to be successful in TV broadcasting.

And then…

Television has changed a lot since 1995. Thankfully, here in Australia we now have more than 3 channels to watch. We have cable TV. We have online TV. And then there’s Netflix and other subscription services. And when there’s nothing to watch there’s always the internet.

These changes started to happen at roughly the same time I began working professionally, and it’s only when I look back about twenty years that I realize how much the landscape has changed.

I really don’t think the commercial TV networks saw it coming – they had a good 50 years where the general public was their captive audience. Once that audience had more choice, they did the sensible thing and chose something else – and I’m not convinced our networks have really come to terms with the new landscape yet.

What I do think has happened more recently is that the broadcast model of television – free to air shows supported by ads – has been exposed for what it is: simply a race for ratings. Perhaps it’s my age, but commercial TV doesn’t even seem to pretend that it’s a creative and artistic medium. While services such as HBO and Netflix have shown that audiences will pay for exceptional content such as Mad Men and Game of Thrones, free-to-air TV seems to be stuck in a race to the bottom, trying to appeal to the lowest common denominator in order to get viewers. It seems to be much easier to produce reality and lifestyle TV shows than it is to foster drama and comedy.

The true cost of free

I’m sure there’s a common saying about how it’s hard to compete with something that’s free. But it’s not impossible, and it’s easier if the thing that’s free is a bit crap.

The broadcast TV that I grew up with is simply a business model, offering free tv programs in exchange for TV ads. It’s similar to how most websites work today, and there’s nothing wrong with it.

But there are other business models, and other ways of watching TV. You can now pay to watch the TV shows you specifically want to watch, whether on Apple TV, Netflix or some other on-demand service. There’s a growing list of shows that have proved that people will pay to watch high quality content – ‘Game of Thrones’ probably being the best example. And if you’re an aspiring writer / director, there are now online opportunities for patron based funding such as Kickstarter and Patreon.

Creativity will not go away, and the industries that rely on it will continue to evolve and change over time. When I look at Richard’s article I find myself agreeing with many of his points – but I don’t think that film and video have lost their value completely. It’s just that the market has fragmented, and different fragments are heading in different directions.

What about me?

When I answered the phone in 1996, I didn’t know any of this. I just thought that if I wrote a funny script then someone would want to make it. I thought TV would be like university – get a bunch of people who were excited about making shows and just do it. In other countries this has happened – there’s a great documentary on The Young Ones that details how it all came together, primarily through enthusiasm.

The sitcom I wanted to make was actually optioned by the ABC – the Australian government funded station – but despite my best efforts it wasn’t picked up for development. Several years later, I teamed up with a few more enthusiastic young writers to see if they could overhaul and improve it. With their help, the new improved version was picked up by the ABC and actively developed for about 2 years. Eventually it worked its way to the top of the development chain and was nominated to go into production, but wasn’t successful. The scripts went back into the bottom drawer, and I moved to London and became a compositor instead.

If you liked this, then check out some of my other articles for the ProVideo Coalition. Here’s another long article that looks at what it was like working in late 90s. And if you’d prefer to watch a video, this 50 minute series looks at how technology has changed video production over the last 15 years.