This picture is worth at least a few words.

So much of the technical jargon around digital content creation is fraught with traps for the unwary. As we’ve previously written, an image sensor “pixel” is not the same as a recorded “pixel” and nothing about a 2/3-inch type sensor actually measures 2/3 inch. Another classic source of confusion is the seemingly innocuous ratio-such as 4:4:4-that expresses the digital sampling structure.

The Sony Tech Guy is hardly the first to notice that these numbers could use a little explaining. In fact, The Guy isn’t even the first on Pro Video Coalition to take up the question. Karl Soule posted a nice explanation back in June.

It’s an oversimplification at best to suggest that the numbers represent ratios of the color samples that make up the picture. This short-form answer papers over some significant gotchas.

The ratios can refer to different things. Sometimes the three numbers refer to the Red, Green and Blue (RGB) channels. Sometimes they refer to black-and-white (luminance or Y), blue color difference (Cb) and red color difference (Cr) channels.

The ratios ignore differences in image sizes. In the days of standard definition, the “4” specifically referred to the ITU-R BT.601 sampling rate of 13.5 MHz. In 525-line 60-Hz parts of the world, this meant a digital image of 720×480. But today, we’ve got a vast range of image sizes from 1280×720 to 1920×1080, 2K, 4K and beyond. Even as 13.5 MHz passes into memory, the 4:4:4 nomenclature lives on, applied to images of all sizes. This often leads to misunderstandings.

Years ago, Internet chat rooms were abuzz with the relative merits of Sony® HDCAM® 24p recording (sometimes described as 3:1:1) versus Panasonic® Varicam® DVCPRO HD® 24p tape recording (sometimes described as 4:2:2). At the time, some commenters supposed that the “3:1:1” format must have fewer color samples than the “4:2:2” format. Because of different image sizes, it wasn’t and isn’t true.

Sometimes, the ratios aren’t even ratios. The three digits typically represent the ratios of the three color channels. So you could be forgiven for believing that 4:2:0 sampling for a Y/Cb/Cr signal means that the Y channel has full resolution, the Cb channel has half resolution and the Cr channel is missing in action. Bit heads among you already know that 4:2:0 means something else altogether.

How can we reveal the important differences that are papered over by these numbers? One of my Sony colleagues uses pictures.

My colleague likes to illustrate sampling with a colored rectangle to represent each recorded channel. The width of each rectangle is proportional to the number of recorded horizontal samples per line. The height of each rectangle is proportional to the number of recorded vertical samples per column. The size of the rectangles then makes it far, far easier not only to compare the different sampling structures such as 4:4:4 and 4:2:2, but also to compare different sampling structures at different image sizes.

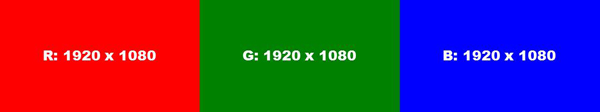

For example, we can represent 1920×1080 4:4:4 as follows:

One way to visualize 1920×1080 4:4:4.

Simply by eyeballing the chart, it’s clear we’re talking about RGB. The corresponding chart for 1920×1080 4:2:2 follows:

Shown to the same scale: 1920×1080 4:2:2.

Clearly, there’s less color information. However, the human visual system is substantially less sensitive to color resolution than to Y-channel resolution. Unless the signal is put through heavy postproduction, the subjective detail is excellent.

Going to 4:1:1 reduces the color resolution in half yet again, as follows:

Once more, with feeling: 1920×1080 4:1:1.

Compared to 4:1:1, 4:2:0 (below) redistributes the color samples for equal spacing vertically and horizontally. Now the Y, Cb and Cr rectangles all have the same proportions, as follows:

Reallocating the color samples: 1920×1080 4:2:0.

As used today, the 4:4:4 nomenclature has no respect for resolution. It didn’t have to be that way. Early in the transition to digital HD, Sony argued that 4:2:2 was tied to the 13.5 MHz sampling of digital standard def. We proposed that if “4” served SD, then the 1080-line HD world should reflect the far higher sampling frequency of 74.25 MHz. The arithmetic is 74.25/13.5 x 4 = 22. Based on this impeccable logic, we told anyone who would listen that the 1080-line HD counterpart of 4:2:2 should be called “22:11:11.”

Nobody listened.

The result is that the nomenclature has lost any tie to sampling frequency and is applied to any image, regardless of resolution. In today’s crazy, mixed-up world, 4:2:2 describes all three of the following images:

From 1080 HD down to SD, it’s all 4:2:2 to me.

So next time you hear claims about 4:4:4, 4:2:2 and the like, we hope you don’t take things at face value. When comparing recording systems, you’re best served by considering the underlying image size and the actual number of samples being recorded.

And what about HDCAM 24p recording? When you peel back the onion, it records 480 x 1080 Cb and Cr samples per frame. That’s 50% more color information than DVCPRO HD tape at 24p. In this parameter, 3:1:1 beats 4:2:2-just as you’d expect.