In this week's somewhat detail-oriented “Answers Occasionally Given,” I start out tackling the differences among color and contrast controls with similar names; in particular, the difference between Lift, Shadow, and Offset controls. Then, I move on to a reader's question about the best stage of a multi-operation color adjustment in which to adjust Luma. It's GRIPPING, I tell you…

Remember, I'm only as interesting as the questions you ask me. If you've got a question about grading, postproduction workflow, or any interesting intersection of production and post, send me an email at ask@www.provideocoalition.com and I may be able to answer it during one of my weekly updates.

This week, colleague Scott Simmons asks:

Some grading applications say “lift, gamma, gain.” Other are “shadows, midtones, highlights.” Some throw “setup” in there. Is there really any difference in the terms or is that different developers using different terms?

I get this question a lot, in different forms, depending on who's asking and what application they're referring to. There's a bit of confusion mainly because not every application or plug-in capable of color correction uses the terminology that is more or less standardized among most dedicated color correction workstation applications from companies like DaVinci, FilmLight, Quantel, and SGO.

In general, there are three mathematical schemes used to adjust color and contrast:

- Lift/Gamma/Gain

- Offset/Gamma/Gain

- Shadows/Midtones/Highlights

Each of these describe a different set of interactions among the traditional three sets of controls that govern the darkest part of the image, the average part of the image, and the lightest parts of the image, respectively. Each has its uses, and I'll describe these controls both in terms of how they affect contrast, and color.

Lift, Gamma, and Gain are the principal controls used by DaVinci Resolve, by Baselight's Video layer controls, and by the color correction features in both Final Cut Pro 7 and Final Cut Pro X (although in FCP these controls are misnamed). Each pair of contrast (or master) and color balance controls have the most influence in a particular portion of the signal; Lift affects the darkest parts of your image the most, Gain affects the brightest area the most, and gamma affects the middle tones the most. However, while each of these regions of adjustment falls off towards the area of the signal they don't affect, they still overlap broadly so that each control influences the neighboring control to a lesser degree. These overlapping regions of tonality can be seen in the graph below.

This graph is only an approximation, as not every grading application's math for defining the overlap of Lift, Gamma, and Gain adjustments is the same. This results in a slightly different “feel” for each application's controls, which will take some getting used to when you switch from one grading app to another.

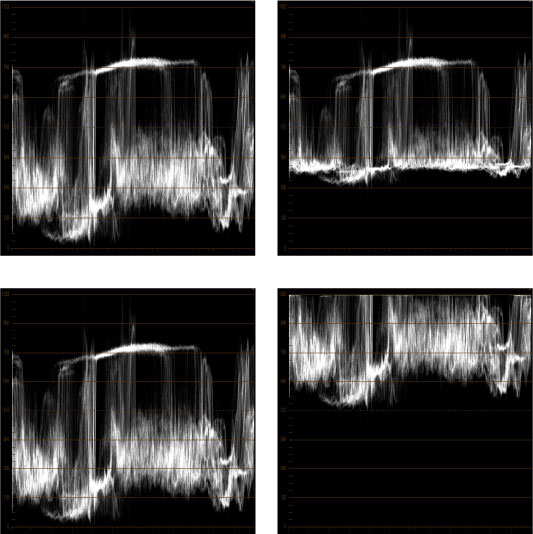

When adjusting contrast, Lift, Gamma, and Gain controls can be used together to scale the darkest and lightest parts of the signal relative to one another. Comparing two waveform analyses, using the Lift control to lighten the darkest portions of the image keeps the white point of the video signal exactly where it is, and squeezes or stretches everything in between.

The Gain control works opposite Lift, darkening the lightest parts of the image while keeping the black point of the signal where it is. Gamma, for its part, redistributes the entire signal between the black and white points in order to brighten or darken the middle values of your image while leaving the brightest and darkest parts of your signal mostly alone.

The whole point of the Lift/Gamma/Gain scheme of controls is to provide targeted control over specific regions of tonality. You can apply a subtle adjustment to the darkest regions of your image without affecting highlights, or you can apply a creative color adjustment to the highlights or middle tones of your image without affecting its darkest blacks.

Some applications, like Adobe Speedgrade, use Offset, Gamma, and Gain as their primary adjustment controls. Others, like Resolve and Baselight, have a separate Offset control that's available in another mode. When used to adjust color balance, an Offset control raises and lowers the entirety of every channel, resulting in an adjustment throughout the entire tonal range of the signal, as seen below. Meanwhile, Gamma and Gain controls work the same as those in a Lift/Gamma/Gain system.

When used to adjust image contrast, an Offset control raises or lowers the entire signal by a single amount. This is also sometimes referred to as a Setup control by applications that reference the terminology of an older generation of analog signal processing equipment (such as the TBC or time-base corrector). Since the signal is not compressed in any way, lifting the signal too high can push the lighter areas of the signal out of bounds, shown below.

To account for this, Offset controls are usually accompanied by Contrast controls, that let you stretch or squeeze the video signal around a central pivot point. This provides an ability to expand or compress image contrast that's similar to using Lift and Gain together, but using different (and sometimes more convenient) math.

You'll typically adjust an offset control first, since that transforms the color and/or contrast of the entire signal and sets your starting point. Offset is great for dropping the black point when the overall signal would benefit from being similarly darker, and for adjusting color balance on images with significant color casts when you want the result to affect the darkest shadows through the lightest highlights. Then, you can use either Contrast/Pivot or Gamma/Gain controls to adjust other parts of the signal as needed.

Incidentally, there's a mathematical definition of Offset/Gamma/Gain, codified by the ASC CDL. CDL-compliant controls work according to the following equation—

output = (input x slope + offset)power

This math maps to your controls as follows—the Gain control sets a slope by which the input signal is multiplied, the Offset control sets a value that is added to that result, and the Gamma control applies a power function to the overall result. CDL-compliant controls are very specific, and applications that don't adhere to this math must of necessity apply a mathematical transformation when either importing or exporting CDL adjustment data to take how their own controls work into consideration.

Bottom line, using Offset rather then Lift, or vice versa, requires a slightly different way of thinking depending on what you're used to, but you can get where you need to go in the end.

Lastly, Shadows, Midtones, and Highlights correspond to the Film Grade layer that's available in FilmLIght's Baselight, the Log controls in DaVinci Resolve, or the Log mode of Autodesk Lustre (although there are subtle differences between each of these sets of controls). What’s confusing is that many applications use the terms Shadows/Midtones/Highlights when they really mean Lift/Gamma/Gain. This was once a forgivable mistake since true Log controls were available only on a few high-end systems, but now that Log controls have become much more widely available, I hope that applications and plug-in manufacturers adopt a more standardized terminology.

The Baselight Film Grade controls were originally designed to manipulate particular gamma profile of film frames scanned as Cineon logarithmically-encoded image data, which explains the highly specific regions of image tonality that each control influences. More pragmatically for the rest of us who don't regularly work with Cineon or DPX film scans, the regions of an image that the Shadows/Midtones/Highlights controls adjust do not overlap one another as widely as Lift/Gamma/Gain, as you can see in the completely rough approximation below.

These controls affect very specific regions of the video signal, although they overlap enough for adjustments to one region to roll smoothly into the neighboring regions. In the image below, you can see the result of raising the shadows contrast control. The adjustment is very much limited to the very bottom of the signal, compressing the shadows up against the midtones of the image, but the shadows compression rolls smoothly into the as yet unaffected midtones.

The zones of tonality defined by Shadow/Midtone/Highlight controls are more exclusive then those of Lift/Gamma/Gain for color balance adjustments, as well. The following screenshot of the Baselight plugin shows three fairly extreme adjustments to the Shadows, Midtones, and Highlights, and you can see in the image at right that each adjustment fits into a very specific range of tonality on a linear gradient ramp.

However, the two points at which each of these three zones intersect are adjustable, such that you can expand the region affected by the Shadows controls by narrowing the midtones, or contract the region affected by the Highlights controls by expanding the midtones. These adjustments make these controls an effective shortcut when you want to apply a color or contrast adjustment to a very specific region of image tonality, even if you’re not working on logarithmically-encoded media.

At this point, most grading applications provide the means to use any of these modes of operation, or even all of them at once within a grade. While you may have gotten used to one or another of these controls depending on which application you first learned, know that each of these modes of adjustment have their advantages, and no one of these is necessarily better or worse then the others overall. It all depends on the type of adjustment you need to make.

Next, reader Jim Bachalo asks:

My question involves node sequencing. When applying a luma curve does it matter whether its on the leftmost or rightmost(last) node? And what about sharpening?

Since most contemporary dedicated color grading applications do image processing using 32-bit floating point math, which among other things conveniently preserves out-of-range data and minimizes the possibility of calculation and rounding errors, it doesn't matter, from a mathematical standpoint, whether you apply a luma curve first or last. This is true of node-based environments like Resolve, or layer-based environments like Baselight or Speedgrade.

The exception to this is whether or not you apply an operation that clips image data prior to applying your luma curve. In this case, putting your luma curve or sharpening operation before the clipping operation lets you adjust the full range of available image data, while putting the same adjustment after the clipping operation will only affect whatever data is left after the signal is clipped.

When considering clipping and compression in a linear series of image adjustment operations, you should get used to thinking about individual adjustments in terms of whether they preserve or discard image detail. Then, choosing whether you want to apply an adjustment to the pre-clipped data or the post-clipped data is a creative choice, as there could be completely valid reasons for doing one or the other. This is true for contrast operations, color operations, and operations for sharpening or blurring the image.

At the end of the day, every adjustment you make is math, and each operation simply manipulates image data in different ways, pushing it to lighter or darker zones of tonality, and potentially clipping or compressing pixels of varying detail in the signal to a uniform value. You need to evaluate every operation you apply, and apply an adjustment to the point of your node tree or layer list where the image data you want to manipulate is optimal for your purposes.