If you’re developing a groundbreaking new product, where do you start? The desktop video revolution was driven by the emergence of non-linear editing systems running on home computers, but adapting them for video production was a gradual process. The products that were being developed and launched at the start of the 1990s were very different from the products that are available now, and apart from the technological challenges every one of them was innovative in some way or another.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can look back and see how 5 different products from the early 1990s were developed from five fundamentally different philosophies.

Following on from my Desktop Video Revolution series, I’m sharing a few brief thoughts and personal reflections from my experiences during the 90’s.

Lightworks

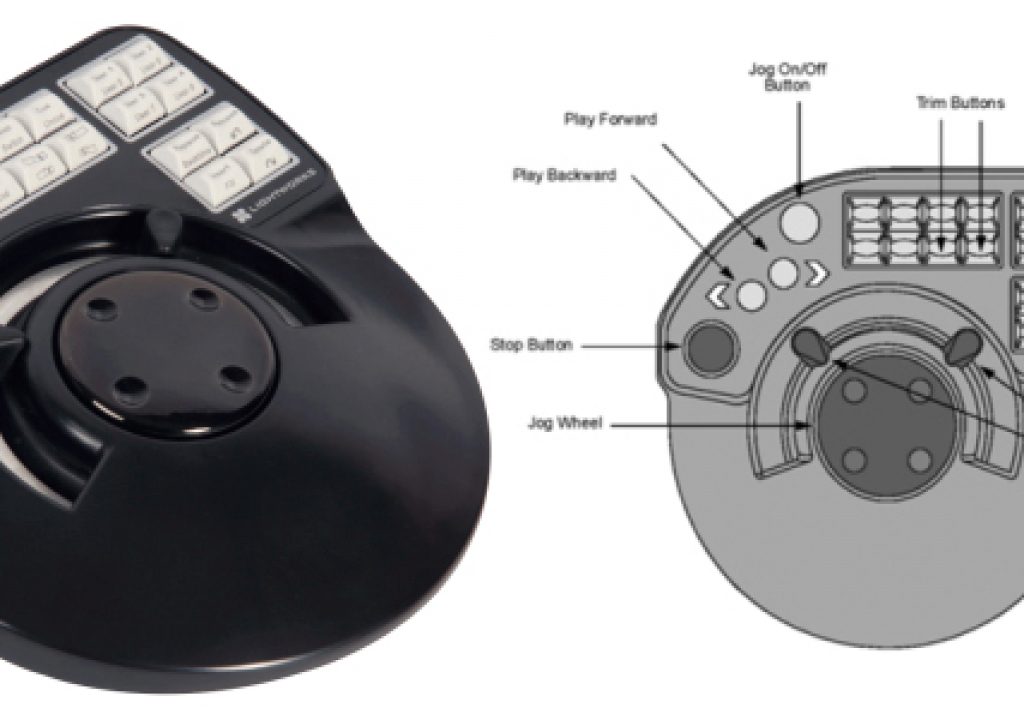

Lightworks was first released in 1989, making it one of the very first non-linear editing systems to become a commercial product. It was developed for the feature film market, and so it was designed to be appealing and easy to use for seasoned feature film editors. Nothing reflects this philosophy more than the iconic Lightworks controller.

Back then, feature films were almost exclusively edited using Steenbeck flatbed film editors, which used a distinctive lever to control playback. The Lightworks system copied the Steenbeck controller and made the new system feel instantly familiar to anyone who’d ever used a Steenbeck.

Lightworks was developed at a time when you couldn’t expect everyone to be familiar with computers, and even the idea of using a mouse was relatively new. The early Lightworks systems didn’t even run as a Windows application, the system still ran on MS DOS, and so the entire graphical user interface was coded from scratch by the Lightworks developers.

Being designed from scratch, the interface looked nothing like the Macintosh or Windows operating systems and by todays standards has a few bizarre quirks – but the designers were very aware that the users of a Lightworks system may have never used a computer before. The Lightworks manual even explained what a mouse was and how it worked, because there was a good chance the intended market hadn’t seen one.

One of the most distinctive quirks of the custom GUI was the use of a shark icon to delete files by eating them – the red shark became something of an infamous Lightworks icon and is still used in the current release over 20 years later. Another cute difference was the way you didn’t “close” a window, you made it “vanish” with the “vanish” button.

We have become so accustomed to computers with “windows” that it’s hard to imagine an alternative, but Lightworks was released a year before Microsoft found commercial success with Windows version 3.0, so perhaps it isn’t surprising that the Lightworks desktop used the concept of “doors” instead.

In the same way that a post production facility might have different edit suites in different rooms, the Lightworks interface showed different projects as a series of doors, which you would select to enter the ‘room’ where the project was being edited. When you created a new project, another door icon was added to the desktop, and you would enter it to begin work.

Unfortunately I haven’t been able to find any photos of the early interface. This is disappointing because the early Lightworks interface was quite remarkable in an ‘OMG look at those colours’ kind of way. At the time Lightworks was being developed, the Macintosh and Windows interfaces were basically monochrome (beveled edges would be introduced with Windows 3.0) so having colours on the desktop was quite revolutionary- especially the vibrant range of greens, reds and purples that the Lightworks used. At a Lightworks user group meeting I went to in 1997, someone told me that the original programmer had hard-coded the interface colour values in assembler code and no-one had been able to find them since. I don’t know if that was true, but evidently the early Lightworks was stuck with a colour palette that was turned up to 11 for some time.

Luckily, an early Lightworks manual was recently uncovered which contains some illustrations of the interface, if not photos. The article is worth a read to fully appreciate how unique the Lightworks was at the time.

Although Lightworks was a software application running on a computer, the iconic Lightworks controller was the primary way that the editor used the system. The mouse was only there for basic navigation, it was definitely a secondary device. All editing controls were done with the function buttons on the edit controller. The keyboard was not really used except to type in text – it could be (and usually was, in our case) pushed out of the way or hidden in a drawer.

So the Lightworks team designed the interface using doors instead of windows, and the Lightworks controller was distinctive and very functional, but once you got beyond the vibrant colours and the slightly clunky mouse, the editing timeline was comparable to the other non-linear systems coming out at the same time. There were two ‘monitors’ – a source and record, just like a traditional video edit suite. The horizontal timeline, with different tracks for audio and video, would be recognizable today as a video editing system. My memory might be faulty, but I think the tracks had sprocket holes to represent the film the system was designed to edit.

Because Lightworks was designed to edit feature films, it was never intended to work with high quality video – it was all about quantity. The video resolution was 352×240 (the same as mpeg 1, or ¼ the number of pixels of a D1 video frame) and quite heavily compressed.

One benefit of low resolution video was that scrubbing worked really well. Using the Lightworks controller, video playback could easily be shuttled forwards or backwards at variable speeds – smoothly and without any stuttering. The simple, intuitive yet very effective playback controls were a huge factor in making the system feel friendly and easy to use. For film editors used to using a Steenbeck, or video editors used to jog and shuttle wheels, the Lightworks variable speed playback worked perfectly.

The low quality video also enabled the Lightworks to play two streams of video simultaneously, for example a picture-in-picture effect. This wouldn’t be possible on some other video edit suites for over 10 years. The longest project I ever completed on a Lightworks was a training video for the hearing impaired. Being able to edit the “master” video full screen, while editing the footage of the sign language interpreter as a small PIP insert in real time, was not possible on any other system.

Interestingly, although the images were low quality even the early systems could work with Dolby Surround Sound, something else that didn’t appear on other video editing systems for more than a decade.

Every aspect of the Lightworks was designed to be familiar to a film editor – not just the controller but the terminology used in the manual and in the interface. In many ways, the Lightworks was the result of developers looking at how feature films were being edited and translating the entire process to a computer, with the goal of making the computer as transparent as possible. There was no indication that the Lightworks was running on a conventional computer – no Windows desktop in the background, no conventional file system to open, save or close projects. Lightworks is the only non-linear system I have seen that almost totally hides the fact it is running on a computer. Once the system was up and running it worked more like an appliance than a software program.

The Lightworks was designed, operated, and to a certain degree marketed as an electronic Steenbeck and every effort was made to hide the fact that there was a computer under there doing all the work. In this regard the designers were very successful and although the underlying hardware was quite anemic, the system was much loved by “serious” editors.

Recently, Lightworks has been completely re-launched as an editing platform. While the current version has nothing in common with the 1989 release except for the name, it’s nice to see them retaining the iconic red shark logo.

Lightworks (early 90s edition)

Released: 1989

Philosophy: Hide the computer

Strengths: Steenbeck-like controller with perfect jog/shuttling

Weaknesses: Low quality video

Fate: Failed to keep up with Avid as technology improved

AVID

Today Avid is the most instantly recognizable name in non-linear editing, and right from the start Avid’s philosophy revolved around providing turn-key solutions. If you wanted an Avid, you bought a complete Avid system. None of this ‘buy a video card and plug it into the computer myself’ stuff. You bought the lot together, from an Avid specialist. Everything came with the Avid as part of the Avid system – the video card, the hard drives, even the colour-coded keyboard.

It’s worth noting that this turnkey approach was so effective that the product name itself – “Media Composer” has been effectively overlooked throughout the company’s history. No-one says “it was edited on a Media Composer”, they say “it was edited on an Avid”.

In this respect, Avid was initially a software company that bundled together available hardware where necessary to deliver a complete system. According to Wikipedia, the first Avid systems were developed on Apollo minicomputers, before being convinced by Apple to move to the Macintosh platform. The fact that Avid were persuaded to change computer platforms demonstrates that they were not locked in to a specific hardware design, and that software was their first priority.

The first Avid Media Composers used a Truevision NuVista video card, but you couldn’t buy a separate NuVista card and then buy the Avid software only- you had to buy a complete Avid system. Although the first Avid system was launched in 1989, it was only in 2006 that Avid began to sell a software-only version that people could use with their existing video cards.

While the first Avid ran on a Truevision NuVista video card, and the Avid ABVB video card from the mid 90s was basically a Truevision Targa 2000, that’s not to say Avid didn’t make their own hardware. It’s just that their primary focus was on the complete system, and if they needed hardware that they didn’t design and manufacture themselves, then they rebranded the hardware made by other companies. The turnkey philosophy meant that customers weren’t faced with problems caused by incompatible hardware, or unique configurations that hadn’t been tested. Avid ended up buying Truevision altogether, so they effectively owned their own video card company.

Avid built their reputation on reliable software and their understanding of professional video editors needs. Designed with an understanding of how editors worked in the past, and what their workflows were, Avid developed software that appealed to existing professionals and had the features and functionality they needed.

Although Avids were sold as complete systems, using an Avid was like using any other computer program. There was no custom controller like the Lightworks, everything was done with the keyboard and mouse.

The Avid interface was designed around the traditional 3-point editing process that had been used by video editors for decades. Edits were performed by defining in and out points, and with a ‘source’ and ‘record’ monitor – exactly as video editors were used to doing.

Looking back, one of the more interesting aspects of the early Avid editing systems is that you couldn’t edit directly in the timeline. The timeline was just a graphical representation of the edits that had been made, and you couldn’t click and drag clips around the tracks as you could in other systems. All editing functions had to be performed in the traditional 3-point manner using the source and record monitors. In this regard, Avid had transferred the existing editing workflow to a computer without radically changing it, or even realizing the full potential that a graphical interface could provide.

It would be many years after the launch of the first Avid before editing in the timeline finally became possible, bringing a new working paradigm to a system designed to reflect the workflows that had been used in traditional tape based systems. (On a personal note, I had looked very closely at switching our Media 100 to an Avid system, but the single thing that stopped me was the inability to edit by dragging clips around in the timeline.)

While Avids were comparatively expensive, the company continued to expand the capabilities of their systems, and to develop solutions for high-end customers. If you wanted to spend a lot of money to get real-time chromakey, for example, you could. Avid were the first non-linear editing system to offer reliable and integrated shared storage solutions, and to see the potential for large editing networks in newsroom environments.

With the development of high-end online systems like the Symphony, launched in 1998, Avid pushed the boundaries of what was capable on home computers and competed directly with online giants like Quantel, Discrete Logic and Silicon Graphics. However as Avid continued to release new models and more powerful hardware, their premium pricing structure failed to reflect the advances made at the lower end of the market.

During the 1990s, Avid was a cheaper alternative to expensive high-end players, but eventually Avid themselves were the expensive, premium benchmark and they began losing marketshare to cheaper alternatives.

For some time Avid has been in a financially precarious position and it’s become a running joke to predict the company’s imminent demise.

AVID

Released: 1989

Philosphy: Buy the complete system.

Strengths: Developers put editors needs first. Understands the high-end market.

Weaknesses: Cost, and the ‘do it our way or don’t do it at all’ software

Fate: Underestimated the market for cheaper, lower-end products – still around, but financially vulnerable.

Media 100

In some ways Media 100 had an opposite philosophy to Avid. At the start of the 1990s Avid was a company driven by software, and they developed their editing software to meet the needs of existing video industry professionals. Where necessary, they used existing hardware from other companies and re-branded it to suit their own needs.

The Media 100 was developed by a hardware company – Data Translation. I remember being told that Data Translation were originally specialists in developing medical hardware, which involved a lot of analogue to digital conversion and signal processing. However the internet suggests that Data Translation also specialized in providing image processing hardware for the US military. Perhaps both are true. The point is that Data Translation were fundamentally hardware engineers.

For reasons I have never heard anyone try to explain, someone at Data Translation decided that their military and medical expertise would be ideally suited to develop a video editing system for home computers. Whatever the logic was behind the leap from hospital equipment to video editing, the company launched the Media 100 as a Mac only product in 1993.

The Media 100 was never intended to appeal to existing editors. The aim of the company was to ‘democratise’ video – to make it available to those who couldn’t otherwise afford it, and make video editing accessible to the masses. The management behind the Media 100 did not intend to compete with Avid, they intended to sell systems to people who could never afford an Avid. This was best demonstrated by their horribly misjudged and generally appalling “kill the editor” ad campaign, which proclaimed that video editors were no longer needed because you could just get your secretary a Media 100 instead.

So Media 100 were a hardware company and initially they had little interest in the needs of professional video editors. The software looked like any other Mac software – nothing was custom designed, no unique icons – it looked exactly like you would expect an application to look if it had been designed by someone following Apple’s design guidelines. The Media 100 software was comprised of many individual, floating windows – so the Macintosh desktop was always visible in the background. The extensive use of the mouse – especially when compared to a Lightworks – made it completely obvious that Media 100 was a software program running on a home computer.

When looking at the Media 100 interface, the most striking difference when compared to other video editing systems was the lack of two distinct source and record monitors, and the small size of the video playback panel on the desktop (you were better off watching an external monitor). The Media 100 only displayed one panel of video, which automatically switched between source clips or the edited program. While in practice this worked very effectively, it was another example of the system being designed by programmers without a background in traditional video editing.

Although the Media 100 could be used to do traditional 3-point editing, it was more efficient to edit directly in the timeline. Although Media 100 lacked many of the software features that Avid had (most notably for film production), the ability to trim, move and generally work with clips directly in the timeline promoted a new approach to editing.

Even if you wanted to edit in the traditional 3-point manner, for many years there was no keyboard shortcut to edit a trimmed source clip directly into the timeline – you had to drag it there from the source monitor using the mouse. This might not seem like a big thing, and Media 100 eventually added keyboard commands to do this, but as video editors had been working for decades by setting in and out points, then hitting an “edit” button in some form or another, the lack of a definitive button to press in order to make an edit was just another barrier to intuitive learning for existing editors.

But aside from the lower cost, what made the Media 100 really popular was its unrivalled image quality, and the ability to add new features through firmware updates. Whatever expertise Data Translation had with hardware engineering or military image processing, it was clearly evident in the superior images that the Media 100 system produced.

Back in the 1990s, professional video was mostly analogue component video – and video editing cards were basically high-end analogue to digital converters. While companies such as Truevision had been making motion-jpeg video cards for many years, there simply wasn’t any other video card around that could match the image quality of the Media 100.

Over time, a series of firmware updates added new capabilities to Media 100 systems without requiring new video cards to be purchased. From 1996 to 1998, the maximum image quality went from roughly VHS to Digital Betacam, and while the original systems worked with square pixels, support for D1 pixels also came through a firmware update. Real-time static titles and previewing of transitions also came via firmware updates – and the fact that these substantial new features could be provided without having to pay for a new video card was groundbreaking. This was possible because Media 100 had designed their own video cards and not simply re-branded a 3rd party product.

Media 100 were the among the first companies to actively promote the idea of “finishing”, or onlining video from the computer itself – before then non-linear systems were seen as offline only tools. Because the Lightworks was designed to edit feature films, the image quality wasn’t an issue. But other systems- including Avid- had never suggested that the images they produced were good enough for final mastering. And until Avid released its Meridien hardware in 1998, even the very best output from an Avid (AVR 77) was sometimes questioned by the broadcast industry.

Before Avid’s Meridien release, and as long as people were using analogue component video, the Media 100 hardware was the best available and its relatively low cost quickly found a loyal user base.

Unlike Avid, the Media 100 company did not sell complete “turnkey” systems. Their products were sold like many other computer products at the time – a video card with software that the user installed themselves.

This meant that to actually put together a working non-linear system, additional hardware was needed. At the very least, you needed two ultra-scsi cards, several fast AV-rated hard drives, and some sort of RAID solution. The Media 100 wasn’t much fun to use without an external monitor and some speakers, either.

Data Translation never offered “Media 100” branded hard drives, or SCSI cards, or complete edit suites – they even left colour coded keyboards up to 3rd parties. Everything apart from the Media 100 video card and the software was up to you.

Although Media 100 maintained a list of “approved” hardware, it meant that many people found themselves with Media 100s comprised of unique combinations of hardware that didn’t always work reliably. RAID and SCSI configurations could be especially troublesome.

A strong online community emerged as users around the world discussed their problems and solutions together, and what was originally known as the “International Media 100 Users Group” has now become IMUG, and they still meet up every year at the NAB.

Media 100 were first and foremost a hardware company, and when the video industry revolved around analogue component video they were strong players in the non-linear market. However once DV and uncompressed SDI became widespread, all of the hardware advantages that Media 100 had were lost and the limitations of the software were exposed.

With the initial success of their low cost analogue products, Media 100 diverted all of their resources into developing a high-end, multi-layered real-time system to compete with Quantel and Discrete Logic. However the system – initially called “Pegasus” but launched as the “844x” – was late to market and extremely buggy when released. It had every feature that the Media 100 user base had ever asked for, or dreamed of, but the price was way, way beyond expectations.

The 844x was impressive but far too expensive for the existing Media 100 users to upgrade to, and it launched years too late to make inroads into the high-end online market- which had never paid any attention to the Media 100 range before.

Having neglected the original Media 100 in order the develop the 844x, the existing user base became more and more frustrated at the lack of new features compared to the competition. As Final Cut Pro gained marketshare, the shortcomings of the Media 100 software became even more apparent and instead of upgrading to the new but expensive 844x, the Media 100 user base slowly migrated away to Final Cut Pro.

Having spent all of their resources developing an unreliable, buggy product that their existing user base could not afford and their intended market did not want, Media 100 filed for bankruptcy and was purchased by Boris FX. They are still around, but I have no idea how many people are working with their current software-only release.

Media 100

Released: 1993

Philosphy: Well, we’ve made this awesome video card. Guess we should write some software for it and sell it cheap.

Strengths: Best image quality from analogue sources, online support community still going strong today.

Weakneses: Never really understood their customers.

Fate: Instead of developing their current product, they diverted all their resources into a new product that failed and took the company with it.

Immix Cube

The Lightworks was a non-linear system that tried to hide the fact it was running on a computer, and in this regard the Immix Cube was similar.

For decades, video post-production had revolved around proprietary “black boxes” that could process video at high levels of quality. Names such as “Quantel”, “ADO” and “Chyron” were synonymous with video effects, and online editing suites were expensive and intimidating rooms where editors punched commands into controllers and all sorts of machines whirred into action.

The Immix Cube followed this paradigm by having all of the video processing done by an external “black box”, with the computer itself only functioning as a controller. This bought all of the benefits of a flexible software interface, and the power of a computer to organize information, but retained the image quality and processing hardware used in existing online video suites.

The Immix Cube was fundamentally a small online edit suite in a box. It functioned in the same basic way as a simple online suite – two streams of video with real-time transitions between them. The Immix Cube placed a greater emphasis on audio tools than Media 100 or Avid, and like the Lightworks, it came with a custom controller.

The Immix cube followed the philosophy that had underlined video post-production for decades – it was a specialized black box specifically designed to do the task that it did. Initially, this gave the system a huge advantage because the custom Immix hardware was much more capable than a Mac with a beefed up video card in it. By putting all of the power in an external box, the system wasn’t limited by the constraints of the Apple Mac it ran on – all the Mac had to do was provide the interface for the software.

The Immix Cube was designed to appeal to video professionals and was promoted as a complete system. It was the first non-linear editor that was capable of high quality, “online” output and it was presented and marketed as an online tool.

While the “black box” philosophical approach gave Immix a huge advantage when it launched in 1995, it soon turned into its weakest link. As computers became more powerful, and software more capable, the benefits of offloading video processing to an external black box soon diminished and eventually became a burden. While Immix followed up the original Cube with newer and more powerful products, their software struggled to overcome their original A/B track paradigm, and users began to look at other systems that offered multiple video tracks in a much more organized and intuitive manner.

While all early non-linear systems were temperamental and often unstable, judging from user accounts the Immix Cube and subsequent products were even more unstable and crash-prone than their competition, which did little to inspire brand loyalty.

Immix Video Cube

Released: 1995

Philosophy: A miniature online editing suite controlled by a computer

Strengths: First non-linear system capable of “online” video quality with real-time effects

Weaknesses: Real-time hardware was great in 1995 but as computers got faster the hardware became a burden, not a benefit

Fate: The buggy software did not inspire loyalty amongst users and they gradually migrated away to Media 100 and Final Cut Pro suites.

Adobe Premiere and Apple Final Cut Pro

Every system mentioned so far – Lightworks, Avid, Media 100 and the Immix Video Cube – has involved some type of proprietary hardware. The philosophical differences between the companies were in how they approached the hardware in the design of their non-linear system.

The Lightworks philosophy was to hide the computer as much as possible, and make the system look and function like its traditional counterpart.

The Immix philosophy was to retain the external, customized “black box” approach that had dominated video post-production for decades, and to produce what was essentially a small online suite that was controlled by a Mac.

Avid were a company initially driven by software development, who adapted existing hardware to suit their needs, and only sold complete turn-key systems.

Media 100 were a hardware company who designed a custom video board and then set about creating the software to use it. With no intention of catering to the professional market, they didn’t sell turnkey systems and relied on the user to install the hardware, software and everything else needed for an edit suite.

While fundamentally different, these four philosophies all relied on custom video hardware in some manner or another, generally because a standalone desktop computer wasn’t powerful enough to process or even play full resolution video without it.

A significant factor in the success of these systems was that throughout the 1990s the most commonly used video formats were all analogue, so digitising video footage into a computer required some type of analogue to digital conversion – that’s basically what the video card was. Software by itself was of limited use without a video card, because unless you bought a complete system there was no way to actually get any video into the computer in the first place.

In this regard, Adobe’s Premiere was an ambitious product that must have been developed with an eye to the future, because Premiere was just a piece of software with no specific hardware required. Premiere relied on the computer for all of its processing power and in 1990, that wasn’t very much.

The point of this article is not to actually compare the features of all the different systems, or to reminisce about the low processor speeds or average amount of RAM in a 1990’s home computer. While it’s worth noting that the largest video resolution that Premiere initially supported was 160×120, the real point is that Adobe saw the potential for a software application that wasn’t tied to any specific hardware.

As the 1990s progressed, the variety of video editing cards available expanded rapidly, and as hardware manufacturers competed with each other to produce more capable products, the Premiere software gained more and more features and the combination became more and more powerful.

The PVC’s Bruce Johnson recently posted an article that shows the progression of Premiere from version 1 to the present day. It’s interesting to note that Premiere version 1 did not use timecode, could not export an EDL, and identified both the video and the audio tracks with letters.

But by the late 90s Premiere was a viable editing solution for the low-end market, and in the early 2000s the combination of Premiere 6.5 with a Truevision or Matrox video card could exceed the features of the current Media 100 systems for a much lower cost.

While Premiere had pioneered the software-only approach to video editing, its biggest problem was that it lacked the development focus of smaller companies. Adobe has always been one of the largest software companies in the world, and Premiere was only one of many Adobe products. Premiere was never quite as powerful, or reliable, or professional as the other non-linear systems around and its popularity with the lower end of the market meant it was generally viewed by serious editors as hobbyist software.

There are reports around the internet that the Premiere development team were frustrated by Adobe, and during the mid 1990s the entire Premiere team left to create a more ‘professional’ product. This is probably not completely true, as developers move between different companies all the time – so it’s possible that several Adobe staff were simply headhunted or tempted by a lucrative pitch rather than leaving of their own accord. Whatever really happened, several of the original Adobe Premiere developers joined Macromedia and started developing a software-only non-linear editing system called KeyGrip. Unlike Premiere, KeyGrip was founded on Apple’s Quicktime technology and was intended for the professional market.

For a bunch of legal reasons that aren’t relevant here, Apple bought the team from Macromedia and renamed the software “Final Cut Pro”. It was launched in 1999 at NAB and certainly generated interest in the press, if not instant sales. Apple managed to sustain the initial buzz with a series of rapid product updates that appeared to directly address many of the concerns professional editors had with the version 1 release. The incredibly rapid development following the initial launch gave Final Cut Pro a real sense of momentum, but although all eyes were on Apple the professional market didn’t jump on board overnight.

If it wasn’t for another Apple product, Final Cut Pro may have ended up as just another footnote in the history of editing software. What made Final Cut Pro really grab everyone’s attention was an iconic, candy coloured iMac that was released a few months later.

When Apple launched the original translucent iMacs the company seemed to regain its mojo. From the brink of bankruptcy, the revolutionary look of the iMac caught the public’s attention and generated a wave of optimism.

At the end of 1999 Apple updated the iMac line and for the first time included a Firewire port, calling the new version the “iMac DV”. This meant that anyone could plug a DV camera directly into the computer and digitize video directly – without the need for a video card or a tape deck at all.

The iMac, combined with Final Cut Pro, could play back DV video and even offer previews of transitions in real-time without any additional 3rd party hardware. Even more startling was the ability to then output the edited master using the camera as a recording device – totally negating the need for an expensive tape deck. In 1999 this was truly astonishing.

Anyone with an iMac, a DV camera and a copy of Final Cut Pro could produce high quality videos and edit them with multiple layers and real-time transitions. This was a completely digital process – shooting, transferring footage, editing and mastering without any analogue technology or generation losses. Being able to do this without purchasing an expensive digital tape deck and an SDI video card was revolutionary, and Final Cut Pro was the software uniquely positioned to take advantage of this technological milestone.

While Final Cut Pro was designed as a professional product, and could take full advantage of high-end video cards for online and broadcast environments, it was the DV support and the proliferation of cheap consumer DV cameras that generated a groundswell of interest and new customers.

By the time Apple released Final Cut Pro 3, the users of other non-linear systems were already being attracted by the richer feature set and lower price. The cost of upgrading a Media 100 to support DV was greater than the cost of Final Cut Pro itself, which prompted many Media 100 users who worked extensively with DV to switch platforms.

In a general sense, the industry was moving away from older analogue video formats towards digital formats – DV for the lower end and uncompressed SDI for the higher end. When uncompressed SDI video cards became available for less than $1000, the price to performance ratio of a Final Cut Pro system was impossible to ignore.

As video production companies planned upgrades to newer, digital equipment Final Cut Pro rapidly gained marketshare as companies like Avid, Media 100, Lightworks and Immix failed to compete with features, price and performance. As production companies switched from analogue to digital, many of them also switched editing platforms to Final Cut Pro.

The software-only approach allowed Apple to make huge gains in marketshare by benefitting from the price wars being staged in the video card arena. With companies like Digital Voodoo, AJA and Blackmagic pushing the price of video hardware down, the high cost of proprietary turnkey systems by Avid, and to a lesser extent Media 100, was more and more difficult to justify.

While Avid’s premium pricing kept its user base reasonably insulated from fluctuations at the lower end of the market, the software-only paradigm used by Final Cut Pro proved too powerful to resist for the majority of Media 100, Lightworks and Immix users. Even Avid had to respond to the popularity of Final Cut Pro and in 2006 started selling their own software-only solution, but by then Final Cut Pro had rapidly expanded its user base at the expense of companies slower to react to the transition to digital video.

The success of Final Cut Pro owes a lot to the DV iMac and the emergence of cheap DV cameras, but it was simply the right product at the right time, designed for the future as the competition was bogged down by the past.

Adobe Premiere and Apple Final Cut Pro

Released: Premiere 1990, FCP 1999

Philosophy: Software only. Bring your own hardware.

Strengths: Cheap! Software is as good as the hardware you provide.

Weaknesses: Can be annoying if specific features of your hardware aren’t supported

Fate: Premiere did great up until version 6.5, then it was dropped from the Mac altogether and stagnated on Windows. Has been recently relaunched for Mac and Windows and is rapidly regaining marketshare. FCP did great up until version 7, then development stagnated as it was re-coded from scratch. Re-released as Final Cut Pro X but lacking many essential features, it was poorly received by angry professionals. Many FCP editors are now switching to Premiere.

If you’ve made it this far and found it interesting, please check out my video series on the desktop video revolution – where I compare the production process of a TVC from 1997 with the process used in 2013.