Jeffrey Radice came into filmmaking in a non-traditional way. He was working in I.T. and making a decent income when friends asked him to fund their moviemaking efforts. After producing two consecutive short films at the Sundance Film Festival, he decided to jump in and try his hand at directing. Ten years later, Radice found himself back at Sundance for his directorial debut with the feature film No No: A Dockumentary. A long-time Adobe software user, he’s now preparing for SXSW, where the film is showing in the “Festival Favorites” category and as part of the inaugural “SXsports.”

Adobe: How long did it take you to make No No: A Dockumentary?

Radice: I started doing development work on the film in 2004 and 2005, but it didn’t go into production until 2010, partially due to Dock's death in late 2008. I had produced shorts for years, but directing a feature film is orders of magnitude more difficult than producing a short, as I have learned.

Adobe: How long have you been using Adobe software?

Radice: My exposure to Adobe production software goes back a long way. When Scott Calonico and I first started making movies in 1997 with The Collegians Are Go!! we used Premiere, and we added After Effects for the shorts that debuted at Sundance in 2003 and 2004. I have over a decade of exposure to Adobe on the production side. No No put all of that knowledge to use. We deployed four teams of animators working in After Effects to implement my vision.

Adobe: Tell us about the film.

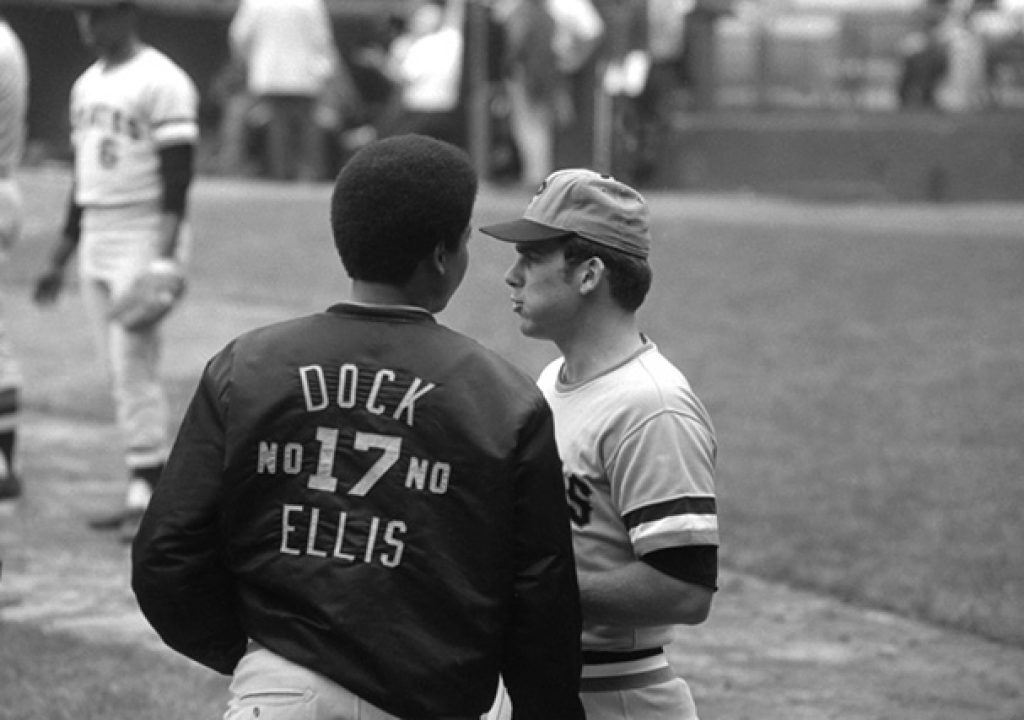

Radice: Dock Ellis was a baseball pitcher and a fascinating character. LSD was a frequent topic of conversation at festivals after I produced LSD A Go Go, which drove me to read Dock's biography by the poet Donald Hall. I gravitated to the idea of painting a non-fictional portrait of the man, because his truth was stranger than fiction. I also hoped to separate his legacy from the most well-known legend about him—that he pitched a no-hitter while on LSD. Dock was deliberate, provocative and a trailblazer in racial and labor rights. He had a sports agent, Tom Reich, before any other ballplayer. He was heavily influenced by Roberto Clemente, Jackie Robinson, and Muhammad Ali. Dock also fought some of his own internal demons but he came clean in the end. At its core it’s a redemption story.

Manny Sanguillén exemplifies a mix of analog and digital treatments

Adobe: How did you use Adobe solutions on the film?

Radice: The two products we used the most were Photoshop and After Effects. We used Photoshop to clean up headlines and photos. Baseball is the sport with the most ephemera and memorabilia attached to it—baseball cards, game programs, scorecards, poems . . . and I wanted to integrate components of that aspect of the game into the film. The 1960s and 1970s when Dock played were an analog era. Some of these items aren’t traditionally found in documentary films. I spent many hours thinking about how to represent our many pieces of analog information in a digital capacity and After Effects helped me achieve the aesthetic I was aiming for. We eventually ended up using After Effects on every still image in the film to add fluidity to even the simplest moves.

Adobe: What were some of your favorite effects in the film?

Radice: Scott Calonico, a director and animator I’ve worked with for years, has refined a technique to animate documents in After Effects. I had two copies of the manuscript for Dock’s biography; one unmarked version and one with pen edits. Scott did an amazing job taking those copies and animating how pieces of the manuscript were redacted (to protect Dock's career).

See an example of Scott’s manuscript redactions: https://vimeo.com/87889895

Another animator, Jake Mendez produced baseball card animations and worked with original illustrations by Kevin-John Jobczynski of a scene where Dock beans Reggie Jackson. With After Effects he took my vision and turned it into a short form graphic novel interstitial within the larger story.

Dock Ellis illustration by Kevin-John Jobczynski

We had a library of archival 16mm, super-8mm, and VHS footage that we combined with our interviews. The lower-resolution transfers degraded when blown up to full frame, especially when compared to our 1080p production footage. Landon Peterson used After Effects to insert elements such as ticket stubs and calendar pages into the background behind the windowboxed video frame. It both allowed us to provide more visual information and made it more seamless to intercut VHS and 16mm.

Adobe: What happened after you were invited to Sundance?

Radice: We had been working with Austin's Arts+Labor on post-production for months in preparation for our submission to Sundance. We submitted a work-in-progress, so when the invitation came back the film was far from complete. It was a mad scramble for eight weeks to get all the remaining artwork cleaned, motion graphics created, and animations placed into the timeline. I had been working with Jen Piper since they cut a Kickstarter trailer for us. Jen not only created complex parallax animations of her own but coordinated my direction among the other animators at Arts+Labor. Arts+Labor has been a foundational partner to our success and they stepped up when we needed them most.

Adobe: Why didn’t you use Premiere Pro to edit the film?

Radice: I built an editing workflow around Final Cut Pro 7 with my employee discount at Apple before I left to concentrate on this movie. I don’t like the direction Apple took with Final Cut Pro X, and it's best not to switch or upgrade your tools in the middle of a project, so there we remained. Taking assets from Photoshop to After Effects to Final Cut Pro 7 was kludgey. There were far too many “sneakernet” moments, which could have been eliminated using Premiere Pro. The ability to easily reflect changes between my graphics cleanup in Photoshop, animations in After Effects, and editing in Premiere Pro is appealing. I’m ready to make the transition to an all Adobe editing workflow.

Learn more about Adobe Creative Cloud

Download a free trial of Adobe Creative Cloud