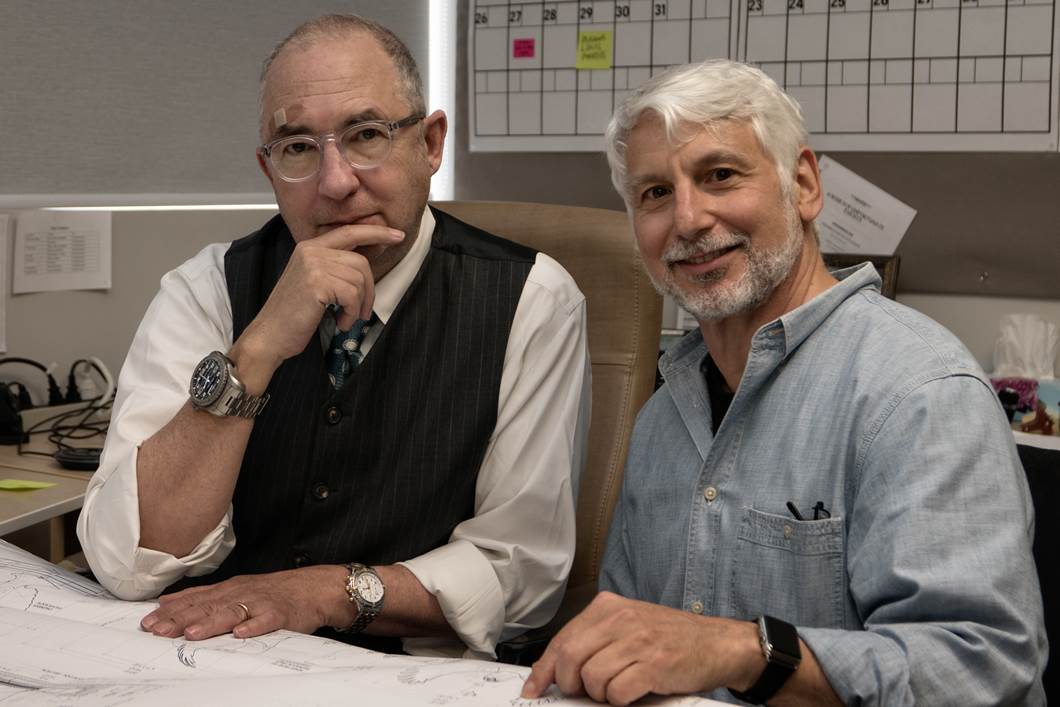

Stuart Bass, ACE is a Primetime Emmy winning editor (for Pushing Daisies) and has been nominated for numerous Emmys for his editing on shows including The Wonder Years, Arrested Development and The Office). He also won an EDDIE for his work on Arrested Development. He’s currently working on Barry Sonnenfeld’s series for Netflix’s, “An Series of Unfortunate Events,” which is a personal favorite of mine.

HULLFISH: So, here we are. A guy named Hullfish, talking to a guy named Bass… Let’s talk about the very specific rhythm of dialogue in A Series of Unfortunate Events.

BASS: As far as the rhythm of the dialogue, because it’s kids acting, it’s my job to artificially manufacture a natural performance. Comedy, a lot of times, needs to move along at a certain pace. The most prevalent example of this is when there’s exposition in setting up a joke, you create a trajectory and then, when the joke comes it’s like you’re pulling the rug out from underneath. So yeah, rhythm is important. I have to say that there is the added factor of the kids. I have cut a lot of shows with children and they are a special case. Their comic timing is not really developed. We have to examine the performed pace, tighten it up or create spaces where there were none. It’s kind of a matter of keeping it moving but finding the emotional moments or the comedy moments where you have to open things up.

HULLFISH: Working with kids is always a trick. Or something similar that I’ve dealt with – which is adults who do not have a lot of acting experience.

BASS: I worked on The Wonder Years , Parker Lewis Can’t Lose, Sabrina the Teenage Witch which comprise about 17 years of my career. All shows with kids. The Wonder Years was the worst case because those kids were really twelve years old. They had no clue what they were doing. They didn’t know what the stories were about because the scripts were fairly sophisticated. You’re pulling syllables from words and sticking it in their mouths and you’re taking performances and playing them backwards, slowing them down and doing all kinds of crazy stuff-Just to make it seem like a continuous performance. On a normal half hour TV show, I can cut eight or nine minutes of show easily. On The Wonder Years, if I cut two and a half to three minutes a day, it was a big day. It was really hard because I was constantly stealing things from other scenes to have the kids react to things and look off in the right directions and all that. Kids are a challenge. I always come back to The Wonder Years because that informed my career, it was one of the most immersive and difficult show I’ve worked on.

HULLFISH: I didn’t think this was the kind of thing that was like David Mamet where dialogue was just machine gun fire. But the language of A Series of Unfortunate Events …there are moments that work because of uncomfortable pauses and there are moments of it that work because they’re so fast and staccato.

BASS: That is the result of a combination of the clever writing by Daniel Handler and Barry Sonnenfeld’s smart performance direction. He’s very careful with his performances and his rhythm and I am tuned into the same tone. Here’s an example: In the very opening, Lemony lights a match and he’s talking and then he drops the match and there’s an uncomfortable moment and then he continues. We had to build that moment with a film rate slow down. It’s almost a freeze frame.

HULLFISH: Wow, I love it. I did notice that moment: he lights the match and he lets it go and he was in the darkness for a moment. And then he lights another match and continues when he realizes that the audience hasn’t changed the channel.

BASS: Right and if you watch the original dailies it went fairly quickly but we made that pause about four times longer than the original. So that’s an example of a place where we had to artificially open things up to make that uncomfortable moment and a comedic moment.

HULLFISH: another editor told me, “In comedy, the ‘dwells’ are where the audience laughs. It’s where you get the joke. It’s where you have a moment to think.”

BASS: I think there’s something else going on. This goes all the way back to something I noted in the Coen Brother’s Raising Arizona which has the stamp of Barry Sonnenfeld their DP at the time. There’s something to be said about holding on a performer a little longer than feels natural. Like when the Baudelaire kids find out that their parents have died and then we just have a shot of these kids staring blankly and playing a little longer than is comfortable. Conventionally you cut to them and you might look for a place where they react. I’m looking for the place where they’re deadpan, it may even be stolen from before the slate. I use slow downs a lot for those kinds of moments. Don’t even want a blink.

HULLFISH: I think that non-editors might be amazed at how much of the timing of performances is due to the editor.

BASS: That is the definition of the art.

HULLFISH: I interviewed the guy that cut Hacksaw Ridge. And he was explaining that towards the end of the movie when the main character has saved the entire company of people, he’s walking down a line of people and he didn’t feel like the line was long enough. So he actually made a jump cut backwards in the line, because he knew, like an editor does, that the audience needs more time to soak this moment in.

BASS: I call that a Mobius strip: where you take the strip of film and you twist it and making a loop getting more time out of it.

BASS: You wouldn’t believe how many times I’ve done that.

HULLFISH: That’s a good little tip.

BASS: In When Harry Met Sally there’s a famous orgasm scene in the deli. Apparently, Meg Ryan’s performance lasted about 2 seconds but the editor used reactions to open it up. It’s all manipulated.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about manipulating time and why is that necessary? Because we’re all trying to get to truth, right? You’re trying to get to the truth of the joke, or the truth of the emotion, and yet manipulating is how you get to the truth. That seems counterintuitive.

BASS: Finding the truth or just what’s funny? Often I am invited to seminars on editing. I like to show a Wonder Years episode that we had given to an assistant to cut. It played like an after school special. The cut was a disaster. It even had a slate in it. I believe that taking out the slates is a minimum editorial requirement. The performances all feel kind of wonky and you don’t get any of the emotion. The schedule was tight and I only had a three long days to take a pass on the episode and clean up rhythms before we needed to lock. The result was a great episode. It earned me my first Emmy nomination. I am very proud of that. It’s educational to show the two versions of the episodes back to back. It’s a great demonstration of the power of editing. You really have to work stuff to make it look right. It’s kind of a gut thing.

HULLFISH: What changed it? Just rhythms? Or was it something other than that?

BASS: It’s rhythms. Sometimes, it’s angle choices, sometimes its performance. But mostly it’s rhythms. That was the case when in the beginning of the assistant’s cut of The Wonder Years, the narrator wasn’t quite matching the picture or the rhythm of the cutting. For example in Unfortunate Events, Violet drops a rock after she heard their parents have perished in a fire, I opened it up as long as I could also used the master to make a longer beat. Barry thought it was too much. He thought it was too cutty. So we trimmed it a bit. But still we slowed the area down from the original performance. Made it uncomfortable.

HULLFISH: That’s one of the reasons why you might try to use one of those rock and roll or slow-mo edits when you’re trying to open the space without making an extra edit to open up the space.

BASS: Right, yeah, sometimes it takes a single and a master: a couple different pieces to open it. Or in Lemony I used a trick of the trade to heighten dramatic tension in that same scene were Poe tells the kids how their parents perished, it also took the pace down to speeds reserved for 60’s Italian films. The original blocking had Lemony exit as soon as Poe arrived. You can still see vestiges of the exit in the final cut but your eye is distracted by foreground movement. I built a split screen around Lemony in the master so he stayed longer in the scene. I found a great piece of film where Lemony looked like he had more to add verbally but was overcome emotionally and walked away. This allowed me to play with the timing of Lemony’s exit. Barry and I then looked at various versions before we landed on the final.

HULLFISH: Was there a place in A Series of Unfortunate Events, where you split the screen so that you’re able to speed up the delivery of performances on either side of the split between two actors?

BASS: There are numerous cases of this. It’s very common to use a split screen on the shots of the kids so they all react at the same time or so their dialog is tighter. The baby Sunny, of course had to be manipulated more to simulate a reaction. This meant at times an easy slide of an area of the frame, but also could require the big guns like face replacement, animation or very expensive 3D work.

HULLFISH: It’s very useful because you can speed up the interaction between two people that are on the master. If you cut, then that’s a cut. And the cut means something different than staying on the wide.

BASS: Or you can use split screens for good matches, especially with over-the shoulder shots. The actor may have moved in a way that doesn’t match the other side so I’ll make a little matte around the shoulder and maybe use a frame rate slow down to get the match.

HULLFISH: I’ve used it where it’s an over the shoulder but you can see the person’s mouth a little bit when they’re talking or not talking and you need the side of the face to somewhat match the dialogue even though you can’t see lip synch. Talk to me about your approach to a scene.

BASS: I use the ScriptSync tool in Avid pretty much exclusively. And I’ve used it since the 90’s. We don’t really use the automatic recording function of it. (Avid has Script Integration which allows for the manual syncing of dailies to the script, or ScriptSync, which automatically matches the dailies to the script using phonetics.) My assistant sets up the script in the Avid so I can access specific lines for each take. It’s changed my editing process so I cut little sections at a time. Traditionally I would sit and watch the dailies in the morning for three hours or so, take notes before starting to edit. But now I just jump right into it. I will watch the master through. Then I’ll watch all of the coverage for just the first fifteen or twenty seconds of the scene. And I’ll work on that little area and I’ll go down and do the next part. So it kind of saves me the time of having to take notes and remember back to things. It’s instantaneous.

HULLFISH: It’s very hard to keep three hours of dailies in your head.

BASS: It also allows me to jump right in. It’s made me very quick. I see everything. It’s not like I’m speeding through anything.

HULLFISH: So you’re watching every camera set up and every take, but only for fifteen or twenty seconds at a pop?

BASS: As much as my little brain can hold. If it’s a simpler scene – if I’m doing a multicam show – I will view the whole scene often in a quad split. But on a complicated show like this, with serious amounts of coverage, it better to break it into small phrases.

HULLFISH: That’s interesting. ‘Cause I’ve heard people who don’t use ScriptSync tell me that they like ScriptSync for when they’re reviewing a cut with a director and the director wants to see his other choices on a particular line. But they don’t like to cut with it cause they feel like they’re not getting the flow of the performance, but you’re watching a big enough chunk of each of those things that you’re getting that flow.

BASS: I’m looking at each take for the best performance, and when I finally see the whole scene together, and some take feels like it’s out of place, then I replace it. The process I use I learned from using a Moviola. I tend to make each edit stick. So if I’m going from shot A to shot B I use trim mode and I get the rhythm exactly how I want it. And if there’s a telephone ring or a gun shot or something that’s gonna help tell the story, I insert it immediately and then get the picture edit exactly right. So once I’ve got the whole scene together, I just do little adjustments. I don’t first create a big open scene of selects and then kind of whittle it down and play with it. I cut it precisely on a macro level, do a quick review of the finished scene, make a few adjustments and move on.

HULLFISH: Does it make it more frustrating, then, for you to get notes?

BASS: It depends on the director. In the case of Barry and certain guys that I work with in half hour comedies like Chris Koch (Scrubs, Apartment 23), Paul Feig (Arrested Development, The Office), or Lee Shallot (The Middle). The veteran directors and producers will have very few notes ‘cause I tend to get it right the first time. I had one producer say my cuts are airable first cuts. The only time I get many notes are from people that don’t have a lot of experience. Or they’re insecure.

HULLFISH: They need to piss on it.

BASS: And at the same time they will complain about the network over-noting them. Piss travels downhill.

I get the cut pretty close. I find I like to get as much preparation before dailies as possible. I love being at the table read. If I can be on a set that’s a bonus. I really like multicam shows where I can be on the floor when they shoot before the audience. I’ll definitely read the script at least once and maybe two or three times. This goes back to editing on film because you kind of have to have a vision when you start of what the scene is. I’m coming in with a point of view. I’m not making the decisions so much when physically cutting. In the old days working on film was like basket weaving. It was a bit monotonous to do the work, the creativity happened before the cut or in a screening room looking at the cut. You couldn’t be cutting off two frames and then running it through and then cutting another two frames. It was too hard to do that. So you kind of get things right. I learned primarily from Stan Tischler, ACE who cut AfterM*A*S*H, on which I assisted. I would watch how he worked, when he cut at modulations; and when he used reactions and for how long; and he had a really good sense of how it was going to go. I sat over his shoulder for a few years. I learned from him to go in with a vision.

HULLFISH: Explain to me what you mean by cutting at modulations.

BASS: It’s about audio. Comedies and their lines tend to be butted up right against each other. And sometimes even overlaps so they go faster. Think the great comedies like “His Girl Friday” (1940) with their rapid fire dialog. Especially expository areas or things where you try to get a movement going before you pull the rug out. Or the opposite of a joke. A tragedy.

HULLFISH: Have you been pigeon-holed in comedy? Or is that just using your talents where you’ve learned to use your talents best?

BASS: There’s no question you get pigeon-holed. But I go with it. I come out of comedy. From the time of elementary schooI I made my own movies and later when I went to art school I continued filmmaking. These were mostly comedies. In San Francisco I was part of an improv group for a few years, so that’s where I’m most comfortable. So I’m pigeon-holed but happily pigeon-holed.

HULLFISH: I’m really interested in exploring the differences between TV directors and film directors ‘cause the way you have to approach them is different, right? The real auteur in TV is the producer or the show runner and the director in TV is somebody that’s more of a gun for hire. Whereas on a feature film, the director is the auteur and the person that you’re getting your final marching orders from. So dealing with those two types of directors is very different.

BASS: I was in a job interview once for a sci-fi channel show, and the director’s there with a bunch of producers and the director says, “OK, we want this show to feel like a feature. We want the editing to be more like a feature than a TV.” I looked over at the line producer and I asked, “That’s so great! I’m gonna get two weeks of extra editing time after shooting ends?” Despite that, they hired me but I turned them down mostly because of the director’s sophomoric question.

The real difference between a feature and a television show is that on a feature, they’re shooting two or three minutes a day and I think the contract is two weeks before the cut has to be ready. A television director has as many as eleven pages a day to shoot and the editor has the day after last day’s dailies to put the cut together. So is in a feature you have more time to do it right and try everything. As far as the hierarchy, in television you tend to have writers as showrunners and 80% of the time these writers’ brains work in a different way than picture oriented people. The dialogue is more important. Some don’t really see picture, and a lot of times they’ll be sitting in my room and looking at the script, searching where to make cuts. The writer would say “Cut from this line to this line.” And I say, “I could do that, but the character will jump across the room.” I had one writer ask “What’s wrong with that?”

Most of these writers eventually become smarter and more cinematic, guys like Vince Gilligan or Mitch Hurwitz who’s obviously not just looking at the words. There are showrunners that do evolve and become more visual. On A Series of Unfortunate Events, I’m very lucky to be working with Barry who’s extremely visual and also watches the pace of the show and he’s very involved in the performances. He carefully rehearses the actors before they start rolling camera to make sure the performance is where he wants it to be. When I’m working with him, we are on the same page. I’ve just been such a fan of his for so long going all the way back to the Coen brothers movies. We kind of talk short hand and use movie references and talk about how we’re going to attack a scene. Also what’s great about collaborating with him, he’s the director and executive producer. Once we get the show to producers cut, which happens very quickly, then it’s just about examining the network notes massaging areas of concern and it’s locked. Barry directed two of the four books, then in our next season we have five books, and he’ll do two of the books.

HULLFISH: So when he directs, is that screwing up the schedule? Because normally you do like a four day director’s cut, and a four day producer cut. So with him it’s all combined?

BASS: We treat each episode as a feature film made from the two hour episodes. We are very quick at locking the shows, so we usually are ahead of schedule. I cut whatever day’s dailies and put music in and sound effects and have it pretty much done by the end of the next day. Then I upload the days work on a server for him. And he’ll give me notes as we’re going. So by the time principal photography wraps, the show is in great shape, temp music and sound effects are in many visual effect temped as well. He might just spend an afternoon with me before it’s locked or a couple days at most. We actually spend more time on the shows that aren’t directed by him. Barry is very focused and like me he’s very compulsive so everything is done right. With director’s who are not as experienced, you end up with things that just don’t quite work or they didn’t see it. Barry will fix things before it is shot. He’ll tell the writers that he wants to shorten a scene or lengthen it because he doesn’t feel its working at that point.

HULLFISH: With outside directors, do you ever feel like you’re the standard bearer for the style of the show? And when you get a director who’s not Barry, what are the politics of dealing with that new director? to say “Ah this is not the way Barry would do it. This is never going to fly” or do you say, “I wanna deliver your vision and let Barry deal with it later”?

BASS: I’m the worst. Here’s what I do – when I have an outside director especially a insecure director or a someone’s brother-in-law,, I just do whatever director says. Better to let them and their ego go to town. Keep their weird camera moves, insert the bad improvised dialog, maybe chopping out the writer’s favorite lines.

HULLFISH: Right, the words are critical writers.

BASS: So, a lot of the time the showrunner will look at the director’s cut and we’ll just go back to the assembly. I’ve had producers watch the first two minutes of a director’s cut and just say, “Uh, let’s just see your assembly we’ll work from there.”

HULLFISH: Okay, now that’s another issue: that idea. I’ve cut a couple of films for a director that wrote the script, in which case, you’ve got someone who’s very committed to those words. Do you feel like the material you work on is just so good that the words are perfect? Or do you feel like “I wanna chop this first fifteen seconds of this scene out”? Or once the scene hits this joke, we don’t need the other two or three semi-jokes after it. What’s your take on trying to convince somebody of things you want to delete?

BASS: Oh I will turn over a full cut so then we can see everything. Because the writer’s are generally smart at story structure, and then we discuss. I wouldn’t cut something out before it got to the executive producer-writer. Sometimes you don’t know, maybe there’s a network note that required a dialog change. They cringed when they put it in, but they put it to placate their overlords. You lift it and you could be stepping on toes! So yeah, you give them a full cut and then there’s a point when I am working with them that I give a suggestion, “Look, this part always bugged me, it’s redundant maybe we can cut it out? Or maybe we can take this scene and integrate it with the other scene?” But I don’t really play with the editorial content of the show until we’ve gotten past the director’s cut. I even do this if the director is the showrunner. It helps to look at the whole show in a version that’s as close to the original script order before looking at story changes.

HULLFISH: One of the things you mentioned early in the interview was that Barry was very involved in the pace of the show. Were you talking about the pace from moment to moment in a scene? Or the pace of the story from beginning to end, and where major story beats end? Or a little of both?

BASS: It’s both. He has a vision and it’s really specific. We’re very in sync on it.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk music. Are you temping with stuff or do you have a list of cues that have been created for the show? How are you putting music in?

BASS: I talk to the composer and usually they will send me samples of scores they did on previous projects. I try to stick to those pieces as temp. This way we don’t fall in love with the Phillip Glass or Danny Elfman score and expect a copy from the composer. That’s not always the case but many studio music departments are insisting we don’t score with unlicensed material. They are afraid even unconsciously the composer will copy parts.

HULLFISH: With temp, there are people that say, “I will only temp with the composer that I know is working so that I know that I’ll temp with stuff that the composer has done before. Or I will temp with anything that gets me to the right emotional core of the scene”.

BASS: On past projects Booker T and the MGs is always the go-to. If you have a scene that doesn’t work – the dialogue is a little slow – underscore it with “Green Onions” and it will make the scene work.

HULLFISH: I’ve listened to Booker T my whole life. My dad listened to Booker T. I love Booker T. I didn’t realize that was the key to editing success! It’s been right under my nose the whole time and I never used it.

BASS: With “Green Onions,” it always makes a scene cool.

HULLFISH: I’m going to have to do an experiment on that. I’ll pull a scene from The Godfather.

BASS: Godfather would’ve been better with some Booker T.

HULLFISH: My dad just told me something that I did not know about TV history: on Bonanza, those guys wore the same clothes in every single episode of every single season because you could just pull a shot from any other day or another scene and use it.

BASS: I always felt jealous of people cutting Star Trek, because it’s the same thing.

HULLFISH: So you can probably relate to the guys cutting Stranger Things then because of your experience with kids.

BASS: There doing a terrific job of making the kids performances look natural.

HULLFISH: The performances look flawless but you know that it’s a lot of work.

BASS: There is a tell. Usually there is a lot of off-screen dialogue. You’re trying to tighten up a pause that’s completely unnatural. If you see the master in the middle of the scene, that’s a give-away of how much work went in to fixing a performance of a kid.

HULLFISH: Is there anything that you’re passionate about when you teach these Editors Retreat things? Is there anything that you feel like is very crucial or central to editing that you like to talk about?

BASS: Not getting boxed in. The director comes in with the plan, the script is a plan and the footage will be pointing to a way of cutting the scene to that plan. And you have to lift yourself above that and be looking for non-conventional ways to approach the scene to make it more interesting. The most important thing is being willing to be a little nutty. If you got something in your mind that seems crazy or if somebody else comes in with a crazy idea, not to shut it down. You try everything cause sometimes you come up with really wonderful things that way.

HULLFISH: If you feel like a director’s idea points to a certain way of cutting things, I wonder how your use of ScriptSync follows that because you’re only watching the first ten seconds of all the scenes. How do you know where the director is going with a scene?

BASS: I know where the story is going. I know where the next scene is and the scene after because that’s more important, what’s being revealed or what the subtext of the scene is and where you are in the story structure. As the editor, you’re telling a story that might not be in the dialogue. There’s an example in Unfortunate Events. There’s a scene in that first episode where Count Olaf is talking about how great he is in the theater but how you should show no ego in the theater. But the scene’s really about the kids having to go through this hell of feeding all the henchmen. But if you watch the cutting pattern, it’s really about the kids’ struggle and the hook-handed man fumbling with his spaghetti and the kids are disgusted by this whole thing. That’s where the comedy and the tragedy is. I’m trying to dig the subtext out whenever I can. In this rare case Barry didn’t get all the shots on his list and it added another layer of challenge.

HULLFISH: What is the difference between cutting that scene so the text is right and cutting the scene so the subtext is right?

BASS: In the scene with Olaf, I could have stayed on Olaf for the story. I don’t have to cut away to the kids and their humiliation. The scene would have been fine, his dialog is interesting, however by digging deeper into the scene there is an added dimension. Also it is the sign of good writing when the text is not explicitly stated as the goal of the scene. A good director will see that and make sure there are character behaviors to cover an element not stated in the script.

HULLFISH: To go back a bit, in that specific scene, where they’re feeding the theater troop, did you say that they ran out of time to do the proper coverage?

BASS: They did. Poor Barry didn’t get to the other side of the table. If you watch it, he only got to the both sides of the table for the very end of the scene. the scene took thirteen or fourteen hours to shoot. I had to figure out ways to cut around the missing coverage to save him from having to come back for another day on the set.

HULLFISH: What was something that he asked you? Did he tell you up front that he didn’t have a lot of coverage? Because a lot of times that’s the reason you’re cutting dailies, and staying up to camera.

BASS: He emailed me and said, “Can you make it work so I don’t have to go back?” It made for a very late night.

HULLFISH: You mentioned in an email to me that you got to direct and edit the opening title sequence for the show. That’s so cool. I loved the opening titles.

BASS: It was so much fun! Barry wanted a main title that would change from week to week, and Daniel Handler, (a close friend of Lemony himself), wrote the lyrics to the song called Look Away. I worked with our talented composer, Nick Urata to hone down the music to a minute with changes so I could squeeze in the credits. Then I saw the credit copy. There were twenty two credits to squeeze in a minute. And I thought, “How do you physically do that?” So I quickly cut a sequence using dailies from the series, to show the a concept as well as the rhythm of what the main title would look like with twenty two credits and the song, which is pretty quick. And Barry says, “Hey, that’s great! Maybe you should shoot it!”

I wanted the main title to reflect the backstory of the series. Lemony is telling the story twenty years later. If you listen to his narration, he is recalling the tragic story of the Baudelaire orphans. He’s living in itinerant hotel rooms. He’s got a typewriter, he has police evidence, bank reports, newspaper clippings, and up on the wall he’s using thread and push pins to investigate the plot. The film survived in cans that have been through fires and time so that the color’s all screwed up. Some are old and black and white and some were video, but the video’s bad.

The next thing I know I am in Vancouver at seven thirty in the morning and I’m pushing pins and yarn into photographs putting together this wall like a crime scene investigator. The DP, Bernard Couture is excited to use his snorkel lens for macro traveling shots and one of those bellow lenses for short depth-of-field focus. I had a shot list with about 80 shots. We broke the crew into two units and got all my shots in a day.

I cut it using my best rock video sense. I’ve got to give a shout out to Sapphire effects – I love Sapphire effects. It gave me incredible control what kind of dust, scratches, the color shifts. There’s a layer where I have specific focus mattes, and another layer where there’s vignettes. I enlisted the help of my friends at Twinart, Lynda and Ellen Kahn (who created the Arrested Development title) to help with the graphic animation design. I am very happy with how it came together.

HULLFISH: Went back to your old art school days. That’s fantastic. I really appreciate the time you spent with me.

BASS: No problem!

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 Art of the Cut interviews have been curated into a book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV editors.” The book is not merely a collection of interviews, but was edited into topics that read like a massive, virtual roundtable discussion of some of the most important topics to editors everywhere: storytelling, pacing, rhythm, collaboration with directors, approach to a scene and more. Oscar nominee, Dody Dorn, ACE, said of the book: “Congratulations on putting together such a wonderful book. I can see why so many editors enjoy talking with you. The depth and insightfulness of your questions makes the answers so much more interesting than the garden variety interview. It is truly a wonderful resource for anyone who is in love with or fascinated by the alchemy of editing.”

Thanks to Evan O’Connor and Todd Peterson for transcribing this interview.