Apple’s inclusion of dual GPUs in every model of their new Mac Pro has caused a bit of a stir (and confusion) among video editors wondering if their NLE of choice can take advantage of them. Applications don’t automatically detect and use multiple GPUs; the drivers must support them, and the software must be written to exploit them. It’s expected that Apple’s own Final Cut Pro can; many seem to assume that Adobe’s Premiere Pro can’t – but that’s not the case.

While working with Adobe to update their Hardware Performance White Paper (which contains tips for non-geeks to optimize their hardware based on the different needs of Adobe’s video software), we learned that not only can Premiere Pro take advantage of both GPUs in the new Mac Pro, you can also install multiple GPUs in an older generation Mac Pro as well as Windows workstations to get similar or even greater performance gains. We’d like to share that information with you here, hopefully boiling the raw numbers down to a few takeaways for you to consider when choosing or configuring a system.

What’s Accelerated

The current version of Adobe Premiere Pro CC can indeed take advantage of multiple compatible GPUs inside the same computer – new or old Mac Pro, or a Windows box like the HP Zx2x series – using either the OpenCL standard or NVIDIA’s own CUDA language. Premiere Pro CC can employ both of these GPUs for rendering and exporting. During real-time playback, only one GPU is used; Adobe has found that in this time-critical application, the overhead required to swap data between multiple GPUs more than cancelled out any speed gains. Note that Premiere Pro can also be set up to use both GPUs, one GPU, or only the CPU. Encoding and decoding different video formats currently runs on the CPU (although the prep for encoding does use the GPU with OpenCL when rendering out to final).

Keep in mind that a computer is not a single chip; it’s an entire interconnected system. For example, the internal PCIe flash drive in a new Mac Pro is extremely fast: roughly twice as fast as a top-of-the-line SATA-connected SSD. This affects reading and writing both source material and caches. You would need to look at a third-party solution such as a Fusion-io in a PCI Express slot to get similar performance out of a different computer.

The new (2103) Mac Pro

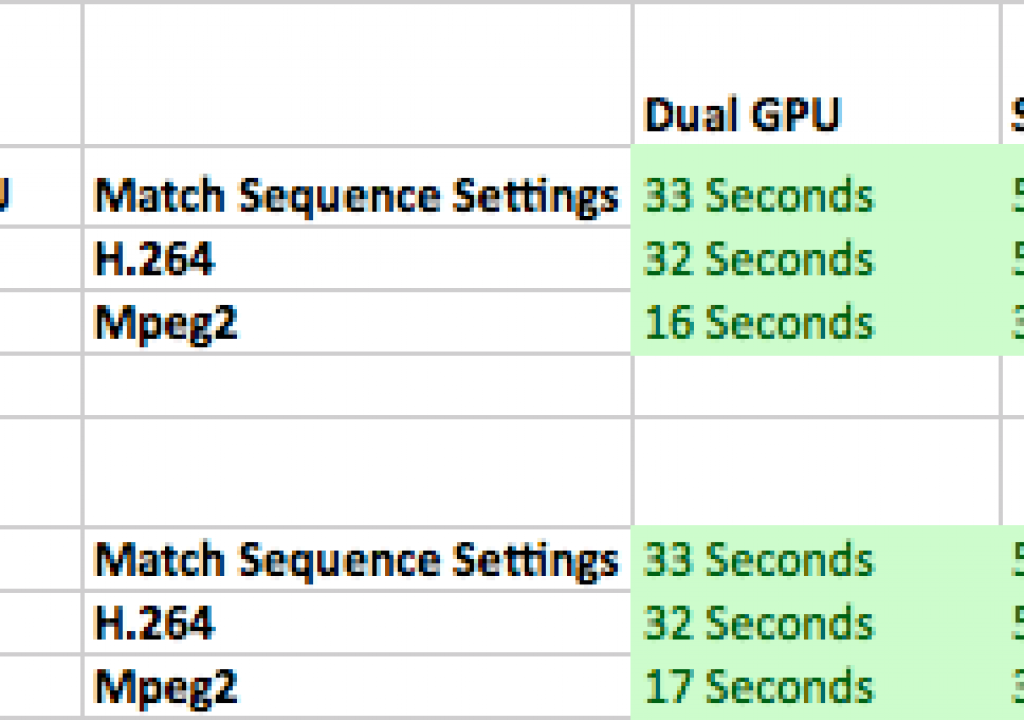

Adobe and AMD ran a series of tests to see just how much difference GPU acceleration made in the new Mac Pro. The spreadsheet excerpt below shows three different tests (a timeline render with effects applied, and two different exports that also included effects) employing two GPUs, one GPU, and only the CPU in two different models of the new Mac Pro:

Compared to running in CPU-only mode on a 2.7 GHz 12-core 2013 Mac Pro, these joint Adobe/AMD tests have found that certain common tasks ran 5.9 to 6.5 times faster on a 12-core Mac Pro using one A700 GPU, and 11.0 to 11.6 times faster using both GPUs. On the 8-core new generation Mac Pro, the performance gains were even more dramatic: 7.6 to 8.4 time faster with a single GPU, and 13.9 to 14.1 times faster with both GPUS being used. By the way, that’s pretty good scaling of performance for dual GPUs; I expected more losses due to data transfer overhead. To keep things straight as we get deeper into this, know that AMD APUs and GPUs (FirePro and Radeon) employ the OpenCL standard.

Older Mac Pros (i.e. 2010)

Although the new Mac Pro is indeed a very slick, well-integrated machine, it is possible to recreate essential parts of its magic by upgrading existing computers. For example, NVIDIA ran their own tests comparing a variety of configurations of the new Mac Pro (4-core with A300 GPUs, 8-core with A500s, and 12-core with A700s), with an older (2010) 12-core Mac Pro that has been upgraded with one or two of their Quadro K5000 video cards as well as a fast Samsung SSD. Their results are below, with the charts being adjusted to show a new 4-core Mac Pro as being the baseline (1x performance):

The takeaway here is that although a single K5000 does not quite elevate an older 12-core Mac Pro the level of a new base model 4-core Mac Pro, under some circumstances adding a pair of K5000s can elevate it beyond the speed of even a new 12-core Mac Pro. This is where you really need to start trading off price versus benefit: The street price on a pair of K5000s plus a good SSD is in the $3000-$3500 range; upgrading is going to be better option for some, while getting a new computer will be a better option for others.

Of course, you can add an AMD video card to an older generation Mac Pro and also see dramatic performance gains; we're looking forward to getting data on their new W9100 card (and will add it to this article once we get them).

Windows Machines

Furthering the “it’s the system” theme, NVIDIA ran a further series of tests including a variety of configurations of HP Z420, Z620, and Z820 Windows machines with their Quadro K5000 and K6000 cards (note that with both AMD and NVIDIA, the higher the model number inside the same family, the higher the performance). They also added a Fusion-io PCIe flash drive card to create their highest-end configuration. Again, normalizing to the 4-core dual A300 2013 Mac Pro as being the performance baseline:

Not meaning to bash the new Mac Pro – indeed, we’re considering getting one for Trish, who has been surviving with a 2008 vintage 8-core Mac Pro – it is possible to build out a Windows system to exceed the performance of a 2013 12-core Mac Pro with dual A700s when it comes to running certain representative tests using with Adobe Premiere Pro.

Yes, money is required; performance versus budget is a decision each individual has to make. The good news here is that you can upgrade existing machines to get performance that competes with the lastest machines, if that's how you want to spend your money. Its worth remember that the new generation Mac Pros come pre-configured with their GPUs, and they cannot be changed after the fact; that's the tradeoff Apple has chosen in system optimization versus expandability. In their case, make sure you buy that system configured up front the way you plan to use it.

Adobe Media Encoder and Premiere Pro (plus more on system performance)

Of course, Premiere Pro is rarely an island; sometimes you need to create assets in After Effects, or convert to a specific file format using Adobe Media Encoder. It so happens that Adobe Media Encoder (AME) and Premiere Pro both share the same Mercury Playback engine code. Adobe explained to us that the performance gain from GPU-assisted rendering in AME is dependent upon the encode job as a ratio of rendering time to encoding time. This is because the GPU is used for image processing and rendering, but not encoding or decoding. Translating that to the real world, tasks such as color adjustments and image size scaling would be GPU accelerated, but H.264 encoding would not. Plus, don’t forget the file system overhead of reading the source file(s) and writing the final output file – this can get significant with larger files such as those saved uncompressed or using camera raw.

Putting numbers to the theory, AMD ran some tests rendering a Premiere Pro sequence through AME for output. The input was a 4k RAW format file, and had dozens of effects applied including the Lumetri color engine, Color Balance, Sharpen, Brightness & Contrast, and more. It was scaled down to a 1080p 24 fps HD frame size (remember that scaling is also GPU accelerated), and encoded to the H.264 format using two pass VBR (variable bit rate), which is a CPU-only task.

Running on a Windows 7 computer with dual 2.7 GHz Intel E5-2680 CPUs, 32 GB of RAM, and a pair of SSDs, the software-only render took 136:22 (136 minutes and 22 seconds). Installing one AMD W9000 into that computer dropped the render time by more than a factor of ten to 11:31; replacing it with their new W9100 shaved it to 10:45. Installing additional GPUs did indeed further lower the times, but the CPU-dependent portions of the render – including H.264 compression, as well as file shuttling overhead – become a larger portion of the cumulative time: Two W9100s dropped the render time to 7:11; three W9100s required 6:46; four W9100s required 6:40.

The takeaway is: A good GPU is almost essential for software that is accelerated by it (such as Adobe Premiere Pro and Media Encoder), and two GPUs can indeed yield appreciable additional speed gains – but when you start going beyond that, the rest of the system may hold you back from enjoying the gains you might expect.

OpenCL versus CUDA

One of our pieces of advice in the Adobe Hardware Performance White Paper is to always make sure you’re using the latest graphic card drivers. When it comes to running Premiere Pro on a system with NVIDIA GPUs, an additional choice is whether to use the OpenCL or CUDA languages (AMD cards or chips only employ OpenCL and not CUDA). Premiere Pro supports both, but in the case of NVIDIA GPUs, you may see a roughly 30% to 40% performance benefit to running then in CUDA mode over OpenGL:

To use CUDA in these situations, Mac users must make sure they install both the latest Quadro driver for your NVIDIA video card, and then the CUDA driver as well – the CUDA driver is not installed by default; you need to do it yourself to realize this speed increase. Finally, open the Project Settings in Premiere Pro and change the Video Rendering and Playback popup to CUDA. If you’re using an AMD card or chips, this setting would be OpenCL. It should be stressed that this is not an overall comparsion of OpenCL versus CUDA; just one manufacturer's implementation of both on their own hardware. AMD's GPUs are designed from the ground up with OpenCL in mind, and do not support CUDA.

Also remember that ray-traced 3D in After Effects is also accelerated using NVIDIA’s CUDA (but not OpenCL). If you rely on this particular feature, it may sway your decision on how to configure your machine – whether you run MacOS or Windows.

Coda

The intent of this article was not to sway you to use FCP, Premiere Pro, or Avid for that matter, nor to make you choose between MacOS or Windows or between AMD and NVIDIA; there are numerous reasons why any individual chooses the computer they do. The new Mac Pro is indeed a very interesting, very well-integrated machine; it is also possible to realize significant performance gains by customizing existing systems. We just wanted to present the facts and dispel some confusion around getting the most out of Adobe Premiere Pro on a variety of systems, including the new Mac Pro as well as other upgraded systems.