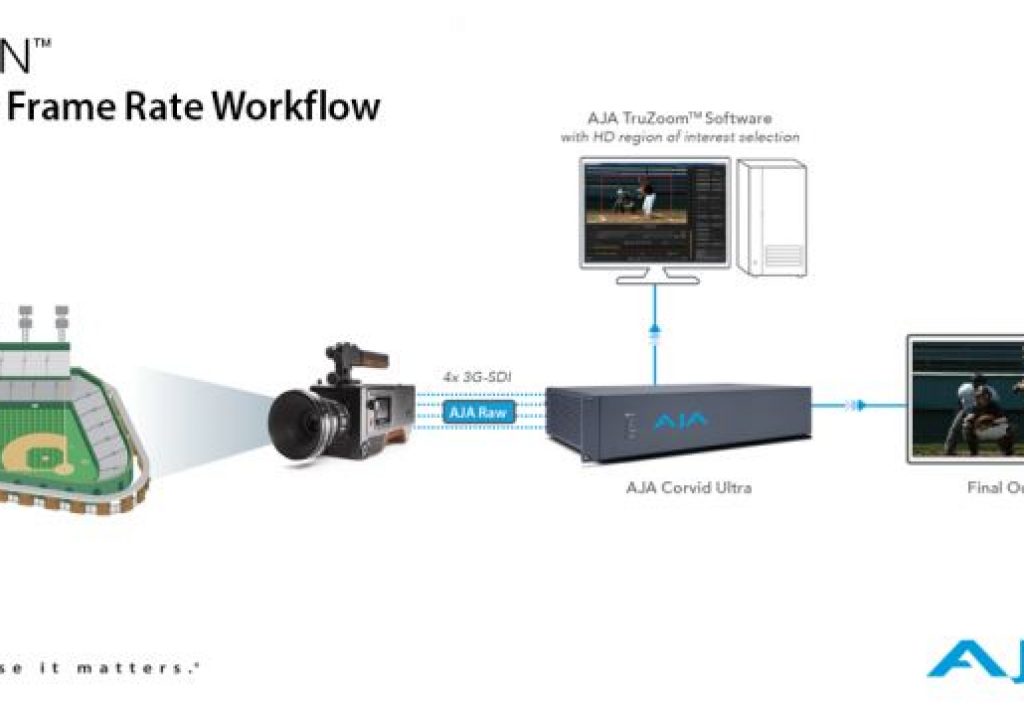

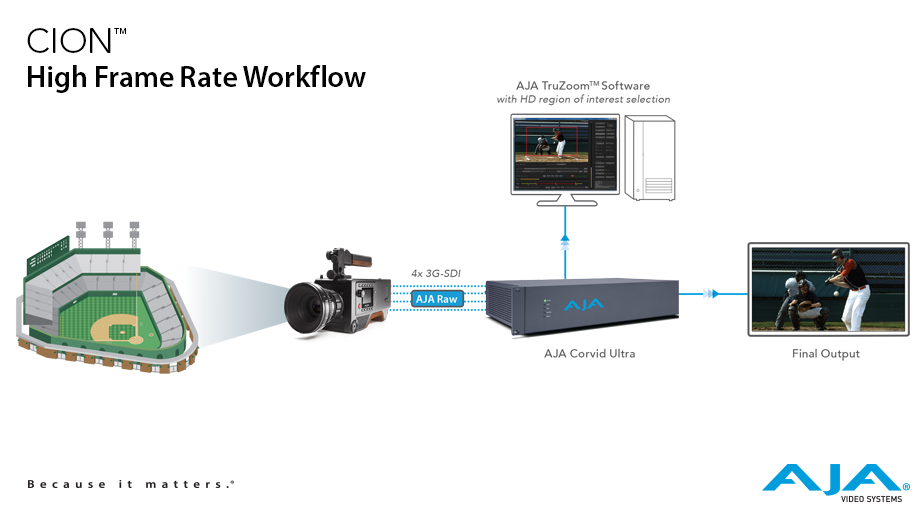

AJA Raw Workflow, from the AJA website

Mergers and acquisitions have been part of the way businesses have operated for centuries, but the incredible pace of technology makes these sorts of transactions more powerful than ever. That’s especially true in the media & entertainment space, where control over as many parts of the production/post-production process as possible means a company can have a huge impact on the pace of these developments. This kind of control can also put a company in a position to give their customers something that’s conceivably greater than the sum of those parts.

That concept was on full display at NAB, where the news about Imagine Communications acquisition of Digital Rapids was made public, and Belden Inc. announced it purchased Grass Valley with the intent to combine it with Miranda. This mindset around consolidation goes deeper than mergers and acquisitions though. Developments like the CION from AJA and Blackmagic’s Pocket and Production Cameras fall into this same line of thinking. Companies that had been totally focused on post-production tools have now crossed over into production. As you can imagine, their production tools play nicely with their existing post tools, so they can sell their customers on a more all-encompassing workflow with pieces and parts that are all designed to work together. In theory, that means a user doesn’t need to spend the time figuring out how everything is going to work, and it means a company has a customer that is going to be buying a lot more from them. It’s a win-win…in theory.

Is this a trend or development that’s actually taking place in M&E, or are the examples from above merely outliers? If companies are approaching the market and their own products with this sort of mindset, do you think individual products will suffer because the company’s focus is on an overall “experience” for the user? Or is it better to have tools that all play nicely together, even if those tools aren’t necessarily the best fit?

Stunning Good Looks

I think it becomes a marketing minefield. For example, when AJA, a company that makes digital recorders, comes out with a camera and competes with camera manufacturers for whom their products are designed… where that does leave them? In a very bad place, I suspect. Suddenly they’re in competition in two areas instead of just one, and there’s crossover. The people who gave them access to products around which they could build recorders are probably going to shut them out.

Part of this consolidation scheme seems to be a loss leader strategy. My suspicion is that the Sony F55 is so cheap because it’s meant to drive 4K television sales by making it easier to create 4K content. (I consult for Sony but this is my own line of reasoning and does not reflect anything I’ve heard while dealing with them.) Blackmagic may be in the business of making cameras in order to boost software sales. It’s become so cutthroat that there’s no one way to make money anymore that’s enough to keep a company solidly afloat, or give it room to grow, so it’s necessary to cross pollinate just to stay alive.

I think there’s a market for products that integrate well with other products, although most of this boils down to user interface design and very few people are willing to spend money on that in spite of the fact that it drives sales like nothing else (if the product is reliable). As for companies becoming integrated… once they spread out to the point where they alienate all their business partners they’re going to alienate their customers next, as they’ll not be able to make sure their products play well with others.

The Editblog

Art’s mention of a (former) production company moving into post seems like a consolidation trend that isn’t going to change any time soon. I think it’s happening all across this industry where traditionally walled silos of one part of the media making process are knocking those walls down and trying to move beyond their silo. It might be slowly and it might be quietly for many but it’s happening.

The reasons are probably twofold. It’s harder than ever to make money in this business. Budgets have been on a downward trend for several years now and you’ve got more and more people competing for the work. If you’re a production company why not branch out into post and try to keep some of that money for yourself. Which brings us to the second reason …

That’s some of the usual doom and gloom talk that we so often hear but maybe this new era of consolidation means the industry is offering up new opportunities like never before. I know many of these production companies are branching out into their own original content where they have never would have thought of (or been able to afford) doing that before. Certainly the Internet is causing consumers to consume more video than ever so that means a lot of businesses that wouldn’t have spent a penny on video in the past is now putting that kind of media into their marketing budgets.

Like any big shift in any kind of business there’s plusses and minuses … and in the end, winners and losers.

The Pixel Painter

Looking in from the other side of the screen, I also see the game changing across the entire spectrum… consumers are increasingly encouraged to become content creators from iPhones and GoPros to DSLRs. This is big business for the prosumer market and social media has set it on fire! Thanks to YouTube, anyone can be a “star” or a “filmmaker” and get hundreds of thousands of views/likes.

It’s not all about making money or even doing production/post as a “business”, per se. Folks who once only dreamed of shooting their own music video or film short can now actually raise a few grand on Kickstarter from friends, family and fans and buy a decent camera and enough gear to shoot/edit their project. They might even go on and do another project or two, but few will continue on to make it a career choice – especially once they’ve gone through the process of learning what to do (usually by learning what not to do first) and what it takes and that they really don’t have what it takes to do it full time. (Wow – filmmaking is HARD WORK and who really wants to work hard these days?) – that at least weeds out most of the hobbyists or keeps them at bay to their social media streams. This doesn’t really affect the working professionals in a global sense, but it does entice manufacturers to cater to this ever-growing and demanding crowd of amateur consumers.

This all leads to a mountain of training needed across the board. Sure, over the years we’ve seen a million books, videos and online training courses out there for almost every piece of hardware, software and production/post concept – and I’ve contributed to every one of those the past 20 years, and I continue to today. But what I’m hearing most from people is how hard it is getting real, hands-on experience and training to better use the production gear, or on the other end, edit the production in post and mix audio, color grade and composite your own VFX/MoGraphix. But where and how? City/community colleges may offer some generic classes; film and art schools may offer some courses without signing up for an extended degree program. But who has time for this commitment and what will you gain in the end? Very few schools can afford to stay up-to-date with the latest hardware/software, so while you may gain some general foundation – which is very important – you may not have the experience needed to tackle a current project or work on a team that is. Workshops and seminars are usually very accommodating and informative, but they’re also usually very expensive and while they may last a day or two, you still aren’t working on a project that will move you forward and continue your education and build your experience – until you actually become part of a team that does. It’s a vicious circle in any case.

What’s the solution then? Where does this leave us today and where will it lead us tomorrow?

I wish I had the answer… maybe somebody out there does…

Imagine Communications already had the signage ready to go for their announcement at NAB 2014

AlphaDogs

What we are witnessing is the end of a bubble that occurred after the invention of moving pictures. Throughout recorded history, most performance artists traveled from town to town in an attempt to earn a living by plying their art or craft. Other than a few standouts who were supported by rich patrons during flush economic periods, most were “Starving Artists”.

With the invention of moving pictures and a distribution chain of theaters, suddenly one performance could reap payments throughout the world. Now an artist could make a small amount per performance viewing, but the scale of those viewings meant big income for the artist. The cost of producing and distributing was so high that only a few companies dared the risk-reward of filmmaking. This allowed many people to make decent livings performing this craft.

The closest comparison model now is writing. Everyone on the planet can afford a pencil and paper. How many are making a living writing? And what has happened to the wages of those who do make a living writing?

The bubble is ending. I believe our industry is heading back to a world of many starving artists with a few sustained by wealthy patrons.

Stunning Good Looks

The closest comparison model now is writing. Everyone on the planet can afford a pencil and paper. How many are making a living writing? And what has happened to the wages of those who do make a living writing?

I agree to some extent. There are still some areas—technical writing or copywriting, for example—where it’s possible to do very well.

Entertainment writing is a crapshoot as you’re creating a product that you hope will sell well and there’s really no telling what the vagaries of the market will dictate this week. It’s also hard to rise above the noise and get noticed.

Informative writing, on the other hand—advertising and marketing, training, and technical writing—should still afford authors a way to make a living as these are necessary forms of communication in our modern age, and not purely for entertainment. Someone will always be willing to pay for these. The question is how low will writers allow payment to go.

My current strategy as a cinematographer is to charge very good money for consistently, reliably beautiful work. There are those out there who still appreciate that and will pay for it as that helps them maintain their marketability as a premium service. Charging very little doesn’t differentiate me from the others, whereas charging good money marks me as a premium brand.

That doesn’t mean they’re willing to pay for it… at least not the way they used to. Marketing and advertising budgets are plummeting. What’s interesting is that this is leading to the growth of the one-stop-shop that both creates and executes the creative, bypassing large agencies (and their overhead) entirely.

As far as entertainment media… that’s going to be the same old crapshoot it always was, except that anyone can now pick up a camera and shoot a feature rather than trying to raise $100K from dentists and relatives the way we used to have to do it. The one advantage to this is that having no money theoretically forces one to tell better stories in clever ways, so maybe the cream will still rise to the top.

I worry most about medium to large feature films and TV series. That’s akin to factory work, with workers relying on a single job to provide them with a living wage for a period of time, and studios are aggressively trying to push those wages down. Also, their willingness to move to wherever the tax breaks are the greatest has created an industry of migrant workers. None of this is good for us as human beings… although I’ve always thought that what happens in the film industry is a good bellwether for what’s coming to the rest of the labor force.

Yes, it’s competitive out there. Yes, rates are going down. Yes, the good people will always be able to make a living. I think the biggest problem with affordable gear, and the consolidation of equipment and expertise, is that the current generation of filmmakers isn’t getting anywhere near the education that I did. Ultimately it doesn’t matter what equipment you use or who makes it, it’s how you use it. We’re discussing whether the companies that make the tools should also make the drywall and the lumber as well, but what we should really be concerned about is that the skills necessary to using a hammer properly are being lost.

Camera Log

Is this a trend or development that’s actually taking place in M&E, or are the examples from above merely outliers?

Mergers and acquisitions are a resurgent trend across the economy, not just in media and entertainment. Company profits and cash reserves are at historically high levels, while investment and employment stagnate in the face of ongoing economic uncertainty. Corporate bosses have money to burn, and nowhere else to burn it.

As The Economist points out in a May 3rd article on the topic (one of many in the past eighteen months), “[t]here have been 15 transactions each worth more than $10 billion so far this year, the most since the record M&A rush of 2007. Taking in smaller deals, mergers are up nearly 50% on last year. … American firms, the most active, are generating record amounts of cash but struggling to do anything productive with it. Having run out of scope for placating shareholders with share buy-backs, and having found that expanding into China and India was no panacea for their dim domestic prospects, they now hope that plausible-sounding mergers will do the trick.”

M&A activity is attractive for executives because it looks like they’re Doing Something, and often the execs do rather well for themselves in such deals (the investment bankers brokering the transactions always do well, so not surprisingly they promote M&A activity to their clients). The larger picture for the companies involved and their customers is much less sanguine; most studies I’ve read indicate that between half and two-thirds of M&As fail to add (or even preserve) value.

As to non-camera companies coming out with new cameras? Cameras are a “glamour product”; everybody wants to build cameras, because cameras are fun, and Jim Jannard showed that it can be done (never mind that Mr. Jannard had squillions of dollars to do it with). That doesn’t mean that cameras, even brilliantly-designed cameras, are necessarily a profitable business proposition: just ask Aaton.

The Brits have a saying: “Sell to the classes, live with the masses; sell to the masses, live with the classes.” Building high-end, limited-volume products isn’t likely to make you rich, while flogging affordable stuff to the Great Unwashed will. GoPro just went public on the strength of their sub-$500 Heroes; they sold over 3.8 million cameras in 2013. Trust me, it’s not the sales to Hollywood pros that gave GoPro a $4.5 billion valuation.

Blackmagic Design’s camera efforts are also largely in the “sell to the masses” camp, and they seem to be doing OK (BMD also has sufficiently deep pockets to support the experiment through its expensive early days). BMD excels at squeezing cost out of their products and offering an undeniable value proposition. I expect they’ll be in this market for the long run (though I wonder about URSA: is there really a market for palmcorders designed for giants?).

AJA’s more rarefied CION is in a trickier place. I spoke with a couple of companies at NAB in the on-camera recorder/monitor market that AJA serves with the Ki Pro, and asked jokingly, “guys, where’s your camera?” Both had identical reactions: “Are you mad? AJA has just opened a bottomless R&D pit that will consume all the resources they can pour into it, with no prospects of selling anywhere near enough $9K cameras to recoup their costs. In the meantime, they’ve diverted resources away from their core product lines, and they’ve poisoned their relations with other camera manufacturers that they depend on to work with their core products. Don’t ever ask us to develop a camera!” I really liked the CION when I played with it at NAB; it’s clearly a product of careful thought, love, and deep dedication…but I worry whether it’ll be able to repay its development costs and thrive in the market.

The ProVideo Coalition experts have weighed in, but now it’s your turn. Continue the discussion in the comments section below and/or on Facebook and Twitter.