Editor’s Note: “28 Weeks of Post Audio” originally ran over the course of 28 weeks starting in November of 2016. Given the renewed focus on the importance of audio for productions of all types, PVC has decided to republish it as a daily series this month along with a new entry from Woody at the end. You can check out the entire series here, and also use the #MixingMondays hashtag to send us feedback about some brand new audio content.

Film with sound has been around a long time. Television and TV broadcast standards have also been around a long time. The world wide web and the internet are relatively new and the content created for it does not follow the same stringent standards of film or TV. In fact, there are no standards at all.

Endless content is being created for the web. Much of this content consists of small crews shooting and cutting their own material, or web content channels, with a staff that cuts and shoots material for their particular content.

A question I get often regarding mixing for the web is – “What is the right way to do this?” Unfortunately, there is not a single answer that will solve all the problems. For television and cable broadcast although there is variation in the many channels audio levels, overall it’s pretty consistent, considering the abundance of content.

There is no such overseer for internet content. There is no standard on frame rates or image resolution or image encoding and compression, there are no standards for audio peaks and for loudness. Each website is a broadcast portal of its own. Each content creator mixes the audio to their own set of specifications. This can make reliable listening experiences over the internet a challenge.

I recently spoke about audio with a company who creates all of their content in-house. They do short field documentary style pieces as well as sit down interviews. These particular content creators are seasoned, professional video journalists. In our discussion I saw that they were pretty well versed in their cameras and its capabilities. There was a range of discussion regarding audio recording and their use of wireless mics and shotgun mics. There were also some differences in how various editors approached the final output mixing levels. These folks shoot the content, then edit picture, and edit and mix the audio. This is a very common workflow for a lot of the content that is available online.

Although there is no silver bullet to make the sound edit and mix happen magically, there are some things that could help. The most helpful tip is to find a consistent range in the overall mix level and then by keeping a close watch on the meters. It’s a good idea to use light compression, depending on the source material, to provide a more consistent level. Use a limiter on the output of the full mix. Video editors or those who have to mix their own content, have a lot going on, however, they should be looking at the overall program level at all times.

As always, the source recordings are key in this sort of situation. When working with compromised material from the start, it makes the sound editing and mixing exponentially more difficult. It’s too much to go into here, regarding best practices for set recordings, but I do have a post with some thoughts on that. Digital audio can, in some ways, be more forgiving than analog audio. If audio is recorded low, it can be possible today with a digital recording to boost the level to an acceptable amount without a lot of noise and hiss. However, a digital recording that is recorded too hot and is distorted and clipped, might be a lost cause from the start.

If you are used to mixing your content to peak at around -2db, or are close to hitting 0db, then there is a great chance that you are already hitting 0db on the output. Do your outputs indicate lots of red meters with crunchy sounding mixes? Turn it all down. Better yet invest in or utilize built-in true peak metering. A separate post on levels and metering here.

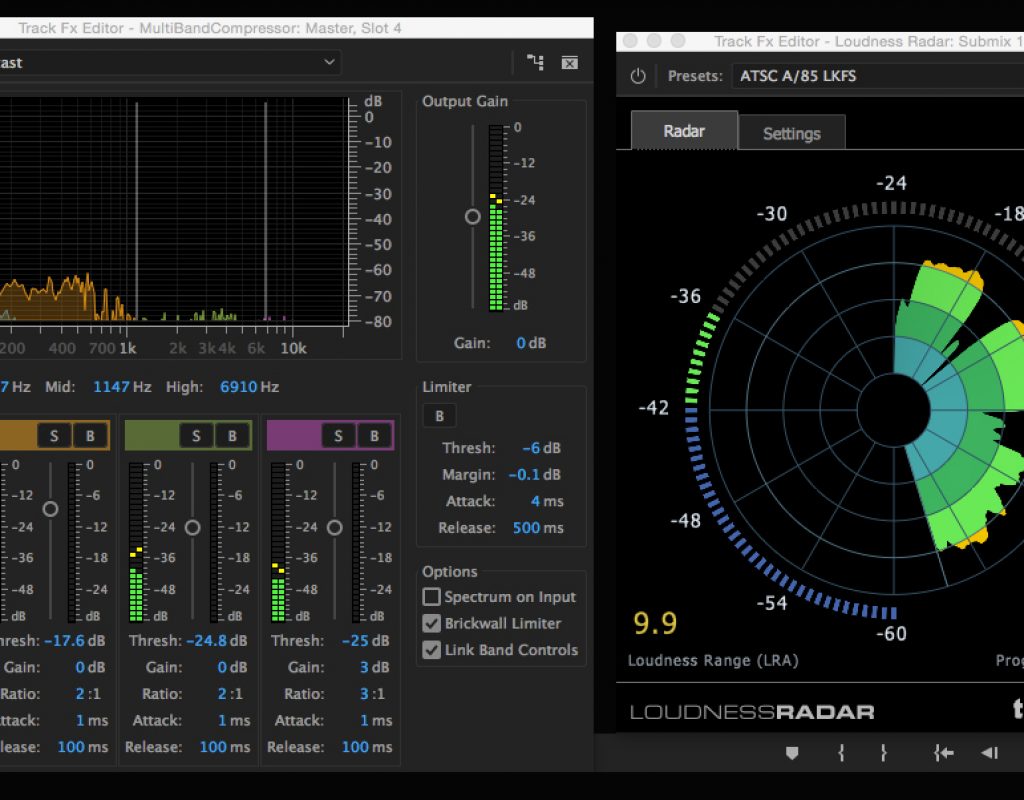

Premiere Pro Creative Cloud, for instance, has included the TC electronic “Loudness Radar” in their set of audio plug-ins. This can be useful because it has a number of built in settings to check for compliance with CALM and similar audio delivery standards. These all include a true peak measure and a loudness standard, which vary slightly but are all pretty close.

When mixing for the web I shoot for mixing peaks to -6db. Aim to create your mixes at a standardized average level – say -20db with a -6db peak, for instance, across all of the content that you produce. This will add a uniformity to your content as you create more and add to your library.

Loudness Radar is measuring for loudness but in LKFS mode. LKFS is the standard adhered to for broadcast content, it uses a type of digital gating that “intelligently” measures the human voice. However, even if not delivering content for broadcast, it is a very useful tool for seeing the variations in your mix. I often measure levels with the Insight meter by iZotope. It can analyze quite a number of various measurements, in a simple to use and easy to configure interface.

Unfortunately, every waveform and every mix of waveforms will create different levels, averages and peaks. Just like every picture edit decision and adjustment, the same level of care must be exercised with each audio choice and adjustment. Adjust the thresholds and the outputs of the limiter, compress and EQ narration or dialog as the case warrants. No matter if the viewing is a on large home theater screen, a laptop, or a cell phone, always find a way to make your content sound as great as it looks.

This series, 28 Weeks of Audio, is dedicated to discussing various aspects of post production audio using the hashtag #MixingMondays. You can check out the entire series here.

Woody Woodhall is a supervising sound editor and rerecording mixer and a Founder of Los Angeles Post Production Group. You can follow him on twitter at @Woody_Woodhall