Screen inserts are one of the most common effects done in everything from Hollywood blockbusters to corporate videos. So why are they done so badly? Because, more often than not, they’re performed by editors and mograph artists who have never been shown how to do them right.

So today I’ll take you through the typical problems with screen insert shots, then show you how to do them the right way. For a detailed walkthrough, watch the video I’ve put together at moviola.com covering the process.

No greenscreens, please!

Greenscreens also add green spill that the poor effects artist has to remove to get things looking natural again. This is a whole level of color correction that’s ultimately completely unnecessary.

Now, is there a situation where a greenscreen is called for? Yes, but it’s surprisingly rare. When an actor’s hair or some other fine detail (like tree leaves) comes between the camera and the screen, a greenscreen allows us to extract a matte of the hair to correctly insert the screen. As I just mentioned, this really doesn’t happen that often, since screens are usually shot with minimal obstructions for readability. There are certainly plenty of fingers and arms that cross between screen and camera, but theses are easy enough to rotoscope with simple shapes, so they don’t warrant green screen keys.

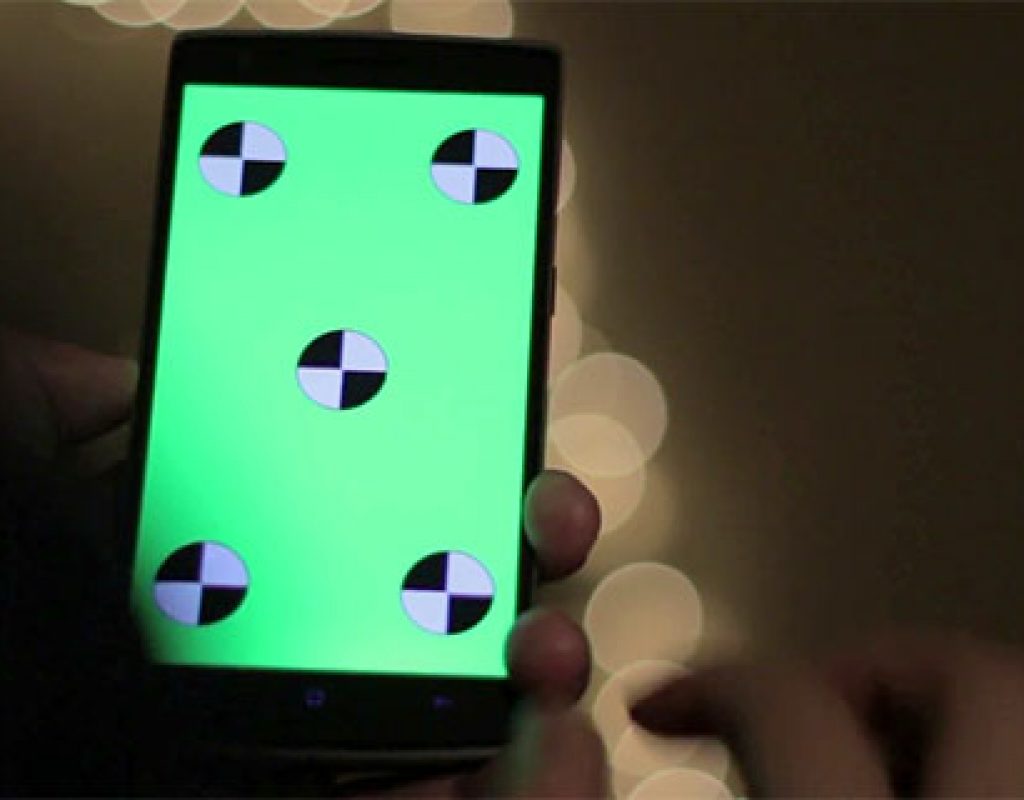

Markers are for whiteboards

A second egregious error on set is to add many and large markers to the screen surface. These are damaging for the same reason. They obstruct the screen reflection and require a heavy paint job.

Take a look at the greenscreen image above. This makes no sense to me. The markers are so large they defeat the purpose of the greenscreen, since they won’t key out and will require significant roto if they intersect with hair detail. At least if the markers had been set to a different shade of green they would have been keyable.

In general, if there are defined corners on the device, like a Macbook screen, there’s no need for markers at all. The tracker will be able to quite happily latch on to the corner detail of the device. Additionally, I’ve worked on shots where the markers were so bright that when they were blurred by motion they leaked into the region outside the screen insert, requiring extensive additional paint work.

Now I do have a confession to make: on more than one occasion my aversion to markers has led to problems. When I work as an on-set VFX supervisor, I try to find natural details on the set (pebbles on the ground, erasers on a desk etc.) to act as practical markers. But occasionally I’ve avoided using markers where there really wasn’t enough detail to track adequately.

On occasion I’ve had to resort to finding fine cracks in greenscreen surfaces to 3D track scenes I insisted on shooting markerless. (Quick side note: it’s much more fun complaining about the idiot VFX supervisor while wrestling with a tough shot in post when you’re not the idiot VFX supervisor.)

So avoid markers, but don’t eschew them entirely. If you’re dealing with a monolithic black surface, you’ll need to add markers. Just keep ’em small and irregularly shaped (if you tear them off a roll of tape, they’ll invariably end up with odd outlines, which is perfect for tracking).

Black is really gray

That black screen you’re staring at when your iPhone runs out of charge? It’s really gray. Unless you’re filming a scene with the blacks completely crushed, black surfaces will be captured to digital with some value higher than a pure “0,0,0” black value. And that iPhone screen can never get any blacker than it is when it’s turned off.

Instead, the screen insert should be added or screened over the top of the source footage (i.e. in After Effects use Additive or Screen blend modes, in Nuke use Plus, Screen, or Hypotenuse). This will make sure that the screen insert is never darker than the original source image and that the reflections are automatically added to the final shot, creating the illusion of a glass overlay.

Your track needs to be flawless

Often you can get a dead lock on focus, but sections of rapid motion still look off. In such cases the culprit is probably motion blur. Many people don’t realize that there are two parameters to adjust with respect to motion blur: shutter timing (aka motion blur length) and shutter offset. Shutter timing is reasonably easy to dial in: just make sure your motion-blurred graphic smears across the same number of pixels as do the corner features or markers in the source footage.

Shutter offset can be much trickier to dial in. Shutter offset determines whether your graphic blurs from: the current frame to the next frame, from the previous frame to the current frame, or somewhere in between. Physical shutters have a falloff of motion blur depending on when the shutter is triggered, and sometimes this won’t align well with the default shutter settings in simulated motion blur.

If you look carefully at the screen replacement in the tutorial footage, you’ll detect that the screen still “feels” a little laggy going through the faster movement frames. That’s because we ultimately should have spent more time dialing in the shutter offset. I doesn’t help that the shot was filmed with a fast shutter timing, producing less motion blur than a traditional 180° film shutter.

Match focus and diffusion softness

This one seems obvious, but obviously isn’t, given the number of horrible screen inserts out there. The screen replacement graphic should have the same “fuzziness” as the original screen itself. If sharp edges on the bezel of the screen device have a two to three pixel softness, sharp edges in your graphic should also be blurred two to three pixels. Use a defocus (lens blur in After Effects speak) filter rather than a generic gaussian blur so that your graphic softens but doesn’t turn to gray mush.

You’ll also need to keep an eye out for shifting focus if the screen is moving through the focal plane, or the camera operator is racking focus during the shot.

Roto the rest

Anything that moves in front of the screen needs to be rotoscoped out. As mentioned earlier, unless it’s hair detail or some other highly varied or semitransparent surface, the rotoscoping should take just a few minutes—a small price to pay for avoiding greenscreens. There are a couple of things to be careful of though: First, err on the side of trimming away too much of a finger or hand than not enough. Rotoscoping right on the semitransparent edge of the object in question will leave some residual black screen around the border, creating the effect of a cheap Photoshop drop shadow. Second, if there’s significant defocus, you may need to completely trim away the soft edge, then add a simulated soft edge back by blurring a copy of the trimmed object, then compositing it underneath.

Watch the entire workflow on moviola.com

Of course it’s one thing to talk about it, another to do it. That’s why I’ve put together a twenty minute Impossible Shot outlining the most common steps. I performed the process in After Effects since that’s what many people have access to, but given the amount of precomposing required I’d strongly recommend doing these kinds of screen replacements using a node-based compositor like Nuke or Fusion (the latter is free and more than up to the task).