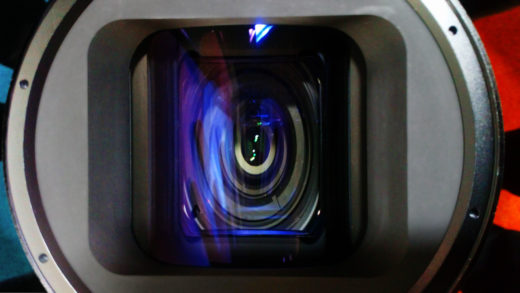

Being an optical designer has been a thankless task for the last few years. You get to spend half a decade bent over a five-figure piece of optical design software, carefully compromising all the ways in which lenses fail in order to crank out a set of focal lengths that’s consistent and beautiful and works in the sort of light where it’s possible to count the photons as they wander past.

And then the Oscar goes to something shot on a lens from the 70s with, objectively speaking, fairly terrible performance. Still, take heart, cruelly-overlooked optical specialists, for we might reasonably conclude that change is afoot. It’s hard to substantiate that impression other than by reference to the general drift of conversations with cinematographers, but it seems some people are starting to realise it’s often a good idea to select a modern lens, a lens which stays sharp all the way down to sub-2 and all the way out to the corners even on large-format sensors. If we want halation, contrast reduction or anything else, find a solution from Tiffen, put a bit of haze in the air, or, for some real fireworks, wave a piece of cut glass in front of the lens.

Worse… or better?

Those are usually much more controllable effects than relying on the failings – because that’s what they are – of old lens designs. Fine, on big shows, people with the lighting budget to illuminate everything to an f/5.6 will do that, and enjoy only the nice parts of a classic lens’s behaviour, although there are comparatively few productions so rich that this sort of approach can be guaranteed for every scene in the script. Much more often, enthusiasts of optical classics are found frowning in consternation as the sun hurries toward the horizon, forcing us into that part of the lens’s performance envelope that we once promised ourselves we wouldn’t go anywhere near.

It’s not said enough that below f/4, many of the most storied lens designs stop being interesting and start being – at risk of being seen as spitting in the eye of someone’s sainted aunt – mushy. The brains of certain post-millennial cinematographers might melt at the idea that f/5.6 used to be an entirely normal shooting stop, but it was, even in the days of sensitivity significantly below ISO 500. As a result, the pictures people get with old lenses in 2022 are not the sort of results most people sought or got when those lenses were more current. We can reach for the old designs, but we can’t necessarily recreate the circumstances that surrounded them.

(This also means that some of the world’s all-time-best material was shot with very similar depth of field to the early 2/3-inch digital cinema cameras, with their B4-mount, small-coverage, sub-f/2 lenses. That combination was widely decried as inadequate, but that’s another story.)

New lens good

What this increasingly means – and naming no names – is that the people most enthusiastic about large-format cameras and the high-precision modern lenses built for them are perhaps not those we might instinctively expect to be among the launch customers for high end new gear. They’re sometimes not the nine-figure narrative features. They’re often more modest productions, people to whom big sensors and big lenses are attractive because they drink deep of even the slightest available light, allowing us to work into the night supported only by someone clutching a glass jar containing a mating pair of geriatric glow-worms.

In the end, it’s not particularly difficult for the rental fees for the best new lenses and cameras to compete against the cost of lighting setups that required to get the best out of a classic bit of glass on a big night exterior. Perhaps even more persuasive is the uncomfortable little itch at the back of a cinematographer’s mind that the disused coal mine scene, shot wide open on a lens from the 60s, might have looked acceptable, even stylish, on the onboard monitor, but risks looking like it was shot through a bathroom window when cut against yesterday’s noon exteriors on a big 4K OLED.

Still, anyone selling old glass on eBay probably won’t be too worried. A growing realisation that we develop new technologies for a reason seems unlikely to immediately affect the mania for classic designs. Cinematography is a peculiarly fashion-conscious field; practitioners of other interpretive arts seem much more willing to live and let live – when’s the last time anyone saw watercolour and oil painters vying for supremacy on an internet forum on the basis of competitive colour gamuts? And sure, fashion-wise, there there will always be someone willing to stroll around sporting the PL-mount equivalent of a purple and yellow zoot suit. Still, fashions change, and there is at least a hint that the once near-universal drive for historic character in lenses is increasingly approached with a healthy degree of caution.