It wasn’t until I worked at the DSC Labs booth at NAB that I discovered The Hawk… and it blew me away. It’s a very simple chart, but it offers a colorist (professional or amateur) the most critical information necessary to accurately neutralize your raw, log, or even WYSIWYG images.

At NAB I was approached by a DP who was looking for a chart for her latest episodic series. “I’m shooting on one coast and color grading is happening on another,” she said. “Which chart do I need in order to bring a still into Lightroom, color balance it, and then add a look on top of it as a reference for the colorist?”

Initially she’d thought the Chroma Du Monde was the answer, but I’ve worked on episodic television shows and they move FAST. The Chroma Du Monde is a very powerful chart but it’s not ideally suited to an episodic schedule, where time constraints rarely allow more than rolling a few frames on a chart placed in whatever light is available. The Chroma Du Monde should be evenly lit for best results.

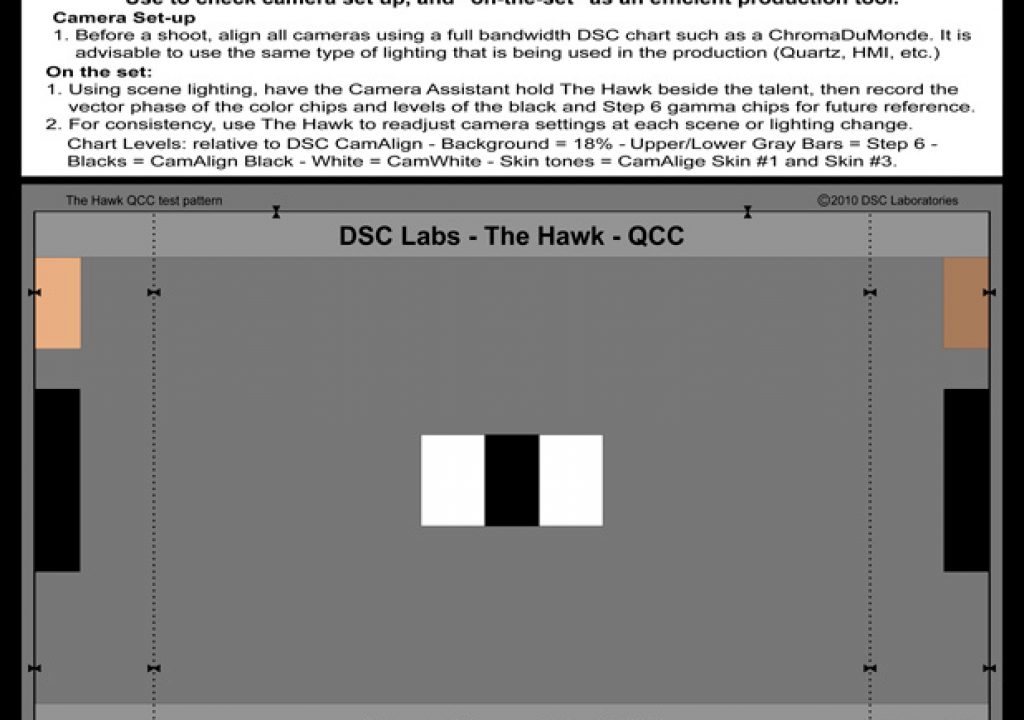

The Hawk, however, is designed to provide the most useful grading information in the smallest package possible:

To break it down:

The white patches provide a perfectly neutral white balance reference.

The black patches provide a perfectly neutral black balance reference.

The gray area around the patches provides a perfectly neutral gray (gamma) reference.

And the brown patches provide an accurate reference for… wait for it… flesh tone.

That’s really all you need to quickly neutralize a shot in color correction: a white reference, a black reference, a gray reference, and skin tone.

Here’s a still that I shot in my living room on my Nikon D7000. I deliberately balanced the camera for 3200K even though the room was lit by ambient window light.

In Final Cut Pro I zoomed in until all I could see was the chart:

Here’s what the waveform looked like before tweaking:

You can see that there’s a LOT of blue in the image and not a ton of red. We’ll need to fix that. After firing up the basic Final Cut Pro color corrector and using the white, black and gray color pickers (in that order) I ended up with a chart that looked like this:

…and a waveform that looked like this:

…and a scene that looked like this:

And that’s exactly what the environment looks like to my eye.

There are lots of charts that offer white, black and gray references, but it’s the flesh tone patches that really set this chart apart. A look at a vectorscope shows why:

It’s easy to balance white, black and gray using only a waveform monitor, but that doesn’t tell us much about the accuracy of flesh tone–which is a range of hues that every human being recognizes at a very, very deep and unconscious level. The waveform monitor can tell us the brightness levels detected by each color channel and whether white, black and gray are neutral, but it’s impossible to detect how accurately flesh tones are being reproduced.

The YIQ color space is the color space used by NTSC television. “Y” is the luminance channel, while “I” encodes hues on the orange/blue axis and “Q” encodes hues on the green/magenta axis. Quite a long time ago it was discovered that the eye is much more sensitive to changes on the orange/blue (warm/cool) axis than they are to green/magenta, so “I” is given more bandwidth than “Q” is.

The question you’re probably asking yourself is: why do I care?

On the vectorscope there exists a line, known as the I+ vector, that is the legacy of the YIQ color space. Here’s the trick: every skin tone known to humankind will fall on or near this line. The circled area on the vectorscope above shows you where The Hawk’s flesh tone patches fall, and they are well within acceptable skin tone range. If that patch skews any farther counterclockwise from the I+ line then skin will look too yellow; any further clockwise and it will look too red.

Here are a couple of interesting tidbits that might be worth knowing:

Colorists generally balance white first, then black, and then gray if necessary. When I used the white color picker in Final Cut’s three way color corrector the results were initially very poor. The white picker brought all the peaks in line with the lowest peak–red–and they all landed around 60 units. Then when I used the gray picker the whites became contaminated.

What I realized is that placing white at 60 units, even just temporarily, puts it too close to the range affected by the gray picker, such that gray balancing has an unwanted affect on the white balance. I discovered that if I used the white picker once and aligned the peaks at 60 units, then increased the gain to boost those peaks higher to between 80 and 90 units, and then used the white picker again, the white peaks aligned high enough on the waveform that they were unaffected when I used the gray picker.

This trick also works in Adobe Lightroom.

Here’s what I’ve learned intuitively about white balancing:

Think of color temperature (measured in Kelvin) as a seesaw overlaid on an RGB parade waveform display. The center post is the green channel. Unbalanced tungsten light sees the seesaw tipping up on red and down on blue; unbalanced daylight shows the opposite. Any time you’re manipulating color temperature you’re changing the balance of red to blue in the signal. Green is unaffected.

If the camera you’re using has a “CC” control (the Arri Alexa is a good example) then you have the ability to raise or lower the green post on which the seesaw sits: CC controls whether the picture skews green or magenta, so raising the post makes the picture green and dropping it makes the picture magenta.

This should sound familiar from the YIQ color space description above. White balance works in the orange/blue realm, while CC works in the green/magenta realm.

A lot of people have asked why DSC Labs charts generally have a glossy finish. I posed this question to David Corley, one of the owners of DSC Labs, and he had this to say:

Given otherwise similar characteristics, ridiculous as it sounds, matte white is more reflective than the glossy. The reason is a little tricky to explain (akin to describing a spiral staircase without using your hands) but let me give it a try:

If you look at a matte chart through a microscope the surface is like a mountain range with millions of tiny peaks and valleys. Consequently light falling on the rough surface bounces from one peak to another and eventually forward towards the camera. Compare this to a glossy white surface where light falling on the surface either goes in and is reflected forwards or, like shining a light on a mirror, some of it bounces off at the reciprocal angle (light falling on it at 45° will be reflected at 45° for a differential of 90°).

Typical bright white matte paper reflects 90% of the light striking it compared to barium sulfate (BaSO4), the reflective reference standard. On the other hand, glossy CamAlign and ChromaDuMonde white reflect 85% towards the camera, 5% being bounced off harmlessly at the reciprocal angle.

So with the matte surface the 5% being bounced around is eventually reflected forward as flare – five parts in 100. Now compare this with matte black where 5% is still bouncing around and coming forward as flare, but the black chip is supposed to reflect only about 1%. This is why we can’t achieve a true black with a matte surface.

The question everyone asks is, “How did you come to develop glossy CamAlign and ChromaDuMonde front-lit charts in the first place?”

Indirectly we have to credit Sputnik, President Kennedy and the Space Race. A client in the space industry was using Ambi/Combi rear-lit systems to align cameras, and they were looking for a smaller lighter test pattern to send into space. They loved Ambi/Combi, but asked why we couldn’t make a precision high dynamic range front lit chart.

Thirty years ago, a Lambertian Surface was the goal in test charts. Lambert said that light falling on a flat surface should be scattered in such a way that the surface appears to have the same brightness regardless of the angle at which it was viewed.

This was a worthy goal, if (and it’s a big “if”) it was possible to achieve and maintain its Lambertian properties, which are easily destroyed even by gently wiping with soft cloth.

Let’s assume we do produce a Lambertian grayscale, we immediately find that the maximum dynamic range we can make is about 64:1 (six f-stops). So we stick on a piece of black velvet and pick up another f-stop. In the early days of B/W television, a dynamic range of 128:1 would have looked pretty good. Today however, with camera systems boasting a range of 60,000:1 or more it’s a different ballgame. Glossy surfaces allow us to create front lit charts with the highest contrast that is printable. Back lit charts allow for a much higher contrast range but require placement in front of an evenly lit, broad spectrum and neutral white light source, which is not always possible.

Another serious drawback of matte charts is that the reflection level tends to change with the angle and type of light source, flood or spot, and sets aren’t all lit with two spots at exactly 45°. “Aha!” you say, but how about the reflection from glossy charts? The glossy chart’s dynamic range is so much higher than a matte chart that the glossy surface produces more consistent results even with some reflection. If the reflection is huge, then simply drop a black flag below the camera lens and tilt the chart slightly so that the black flag reflects in the surface of the chart.

The back of The Hawk has three additional features: a framing guide, a perfectly neutral “CamWhite” for a neutral white balance, and a “CamWarm” white balance patch that, when used as a white balance reference, warms the image by fooling the camera into adding orange and magenta by removing blue and green.

The Hawk is the perfect chart for productions that move very, very quickly. It has all the information necessary to reproduce an accurate and neutral image, whether this is done in a grading suite, desktop color corrector or photo editing software such as Adobe Lightroom. And it’s such a simple tool that it’s hard to use improperly. It can be found here and here.

Click here for a slightly longer explanation of the YIQ color space.

Disclosure: I have worked as a paid consultant for DSC Labs.

Art Adams is a DP who likes to use tools that help him work fast. His website is at www.artadamsdp.com.