Eddie Hamilton’s list of credits is envious, starting with feature film editing credits in 1998 and kicking into high gear with 2010 with the Kick-Ass movies, X-Men: First Class, The Loft, Kingsman: The Secret Service, and now Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation. Eddie didn’t even study film in school, but knew that this was his dream and his goal and did everything he could to work his way up from post house runner to film editor by soaking up knowledge like a sponge, contesting conventional wisdom and being just as concerned about the theory of story as with the technical aspects of cameras, NLEs, codecs and media management.

Eddie Hamilton in the editing suite for Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation.

Eddie Hamilton’s list of credits is envious, starting with feature film editing credits in 1998 and kicking into high gear with 2010 with the Kick-Ass movies, X-Men: First Class, The Loft, Kingsman: The Secret Service, and now Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation. Eddie didn’t even study film in school, but knew that this was his dream and his goal and did everything he could to work his way up from post house runner to film editor by soaking up knowledge like a sponge, contesting conventional wisdom and being just as concerned about the theory of story as with the technical aspects of cameras, NLEs, codecs and media management.

Hullfish: Let’s start at the beginning of your editing process. How do you prepare for a film edit? What are some of the things you ask your assistants to do and what are you doing as dailies are starting to come in?

Hamilton: That is a very, very good question. For a film like Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation obviously I had seen the other four movies over the years, but I did my homework and watched them all again and made very sure I was clear on the history of the show. I remember watching the TV show when I was younger and I watched the TV show again. Another thing I did that I find very useful is that I listened to the soundtracks for the other four movies very, very closely and intensely. For a few weeks I had them on my iPod on repeat and I would listen to the music cues and try to get them inside my head so I had a good grasp of the library of existing music that we could use as temp score because I often find that is quite the battle, especially on lower budget films where they don’t have a budget for a music editor. I like to really prepare my knowledge of temp music as much as I can. Interestingly, on this film Christopher McQuarrie (the director of Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation) did not like cutting with temp score at all. He likes to cut completely bare and watch the entire assembly with no music, because his opinion is that if you can get the scene playing with no music it can only improve with music, which I agree with. And a lot of the time with transitions and extended sequences you have to imagine what the music will be doing. Other things that I prepare? That’s a very good question. I like to watch the pre-vis and study the pre-vis because quite often the visual effects team will have been putting together pre-vis of the more complex action sequences, so I’ll have become very familiar with that. For my assistants, it’s more about making sure that the cutting room is set up a good few days before the shoot starts happening. You test the entire workflow from beginning to end. You get test footage from all of the cameras you’ll be using to check if all of the metadata is going to translate from beginning to end. Try and get the colorist that you’ll be using to take some footage from the different cameras – most of our footage was 35mm anamorphic negative with a little bit of Alexa 65 and a little bit of Blackmagic Cinema camera. Test the whole process. Test the VFX workflow thoroughly as well. Make sure any kinks in the color workflow are sorted out. And then I have a huge library of sound effects which I have in bins, so I bring those into the project. Then I start work.

Hullfish: Jumping back, I’m fascinated with the idea of listening so intently to the scores of the previous movies. Since the director doesn’t even want temp score, is that just to get your head in the right place to edit this type of movie?

Hamilton: It absolutely does. And also watching the other movies, and where they use music. Because obviously most of the Mission: Impossible movies have a set-piece which is pure suspense with no score. And we, I hope, succeeded to do that with Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation There’s a sequence where Ethan Hunt has to dive into an underwater computer vault and his colleague, Benji Dunn, played by Simon Pegg is walking through a highly sophisticated security corridor with combination locks, gait analysis cameras and we played that purely for suspense and didn’t use any score until the very end of the scene, so you’ve got several minutes there, a bit like in the very first Mission: Impossible when they break into the CIA, it’s all just pure suspense. So all that stuff I’m kind of thinking about as the scenes are coming together and I’m imagining ways of transitioning between scenes.

The MI-5 editing team – Tom Harrison-Read, Martin Corbett, Eddie Hamilton, Rob Sealey, Chris Frith

To go back to the question of what I do when dailies roll in: I task my assistants to prepare bins as quickly as possible so that I can start work as soon as possible. One of the most important things that an editor on a movie of this size needs to do immediately is warn the production if they haven’t got all the coverage they need to tell a particular story in a scene. So one of my first jobs is to skim through the footage quickly – look at what I’ve got and see if I can tell the story with the footage I have. And if I don’t, I need to let the production know so that they can send another unit on to the set to pick up some insert shots or sometimes re-shoot a couple of lines of dialogue if the scene requires it. That is so important because so much money is being spent every day and obviously if a set is still standing, it’s a lot easier to light the set and shoot a couple of inserts than it is to do it later, so that’s kind of the first thing. Then I have my assistants start building up a massive selects reel for each scene, a HUGE timeline of every single line of dialogue delivered chronologically from every different camera angle, so I can see all of the wides, all of the mediums, all of the tights. And then, I have each shot size on a different layer on the timeline. So all of the wides on V1, then V2 for overs, V3 mediums, V4 tights etc. for each line of dialogue, so when I want to audition all the different deliveries of a single line I can just click on it and watch the 40 deliveries for that line. I was doing that myself to begin with because I like to be really thorough, but the time pressures on this film were so intense that I ended up delegating that task, which is very time consuming, to my assistants and then I could effectively assemble the scene quickly and then review options of takes very quickly, especially if the director came in and wanted to change something. Everything was just there and I could run stuff and he could pick another take to swap out and try.

Hullfish: I love working from selects reels myself. But what about using script integration in Avid (ScriptSync, minus the automatic audio syncing). Because you can also audition dozens of different reads using that tool. That will let you pull off basically the same thing without the need to build all those reels.

If it’s an action sequence I will watch the footage and build up selects reels of stuff and slowly piece the sequence together – always working without any sound. Just working silent. Imagining all the music and building the scenes up from there. Always trying to do it very fast so I can communicate with the director and producer anything that might be useful to them on the set.

Hullfish; When I was writing my “Avid Uncut” book, one of the editors gave me the full Avid Project (minus media obviously) for a blockbuster Hollywood movie and I was shocked to see 5,000 bins.

Hamilton: I don’t think I have quite that many bins, but I am ridiculously organized. I once worked beside (Oscar-winning editor) Pietro Scalia on a movie called Kick-Ass. And that was the first time I had ever really worked alongside a double-Oscar winner or anyone who was really working at the top, top, A-plus level of editing and I remember him saying how he had come in to help on another movie and how the project was in poor shape and you couldn’t find anything and couldn’t find any archived cuts and I remember thinking to myself, “I’m not going to make that mistake if I ever reach that level, I’m going to be meticulous and be so organized with my project structure that if any other editor came in and sat down on my machine for any reason, they would be able to find everything as quickly as they would need to.” So I like to think that I have a good attitude towards project organization and archiving of versions of cuts and every single cut of every scene and every version is archived in a way that I can find it very quickly. And the project is very easy to navigate and I really hope that if you were to look at one of my projects I think you would be pleasantly surprised at how easy it is to navigate.

Hullfish: What are some ways you organize the project – the bin structure – to allow you to find stuff on a project of this immense scale?

Hamilton: It’s very straightforward. It’s broken down by sequentially numbered folders, so for example it would say:

- Cutting Copy,

- Scene Bins,

- VFX,

- Music,

- Sound Effects,

- Deliverables,

- Graphics,

- I usually have one at the bottom which is called Basement or Cave and then all my assistant’s bins are in there – all the sync bins and the various turnover bins (turnovers are shots sent to the effects department), and any toolbox things they’ve got.

But effectively you’ve got sequentially numbered folders. And if you look in the Cutting Copy bin, you’ve got the seven current cutting copy reels and underneath it it’s got a cutting copy archive and in there I’ve got dated versions of every version of the movie that we’ve ever screened or exported for somebody, all listed by date. Then down in the scene bins I’ve got subfolders for scenes from 1 to 20, 21 to 40, 41 to 60, etc. and then in there you’ve got all the bins laid out, so it’s very easy to find them. Then when I list all of the bins, one of my assistants on Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation had done something on another film that I’d never done. Scene 41 for example started at slate 41 and goes A, B, C, D, E, F and sometimes goes to AA and then AB, you would have several bins and previously I would do 41 part 1, part 2, etc., if it’s a big action scene, but what he did which was quite clever was he would go 41A-G with slates A to G in that bin. Then 41H-M for example. So you could easily find the slate as well if you were looking for a particular slate.

I also always add an abbreviated description of the scene in there so it’s easy to find. So it’s that kind of stuff. You can find the temp music easily because it’s all in the music bin and visual effects related stuff is in the visual effects folder and it’s that kind of stuff to stay really kind of meticulously organized. I also don’t like using all caps. I like using caps for the first letter and the rest lower-case. I find it easier to read. Easy on the eye. Nerdy stuff like that. I think if you’re meticulous about it, it makes for a pleasurable experience day to day. Which, when you’re living with something 12-14 hours a day for nearly a year, over time it all adds up.

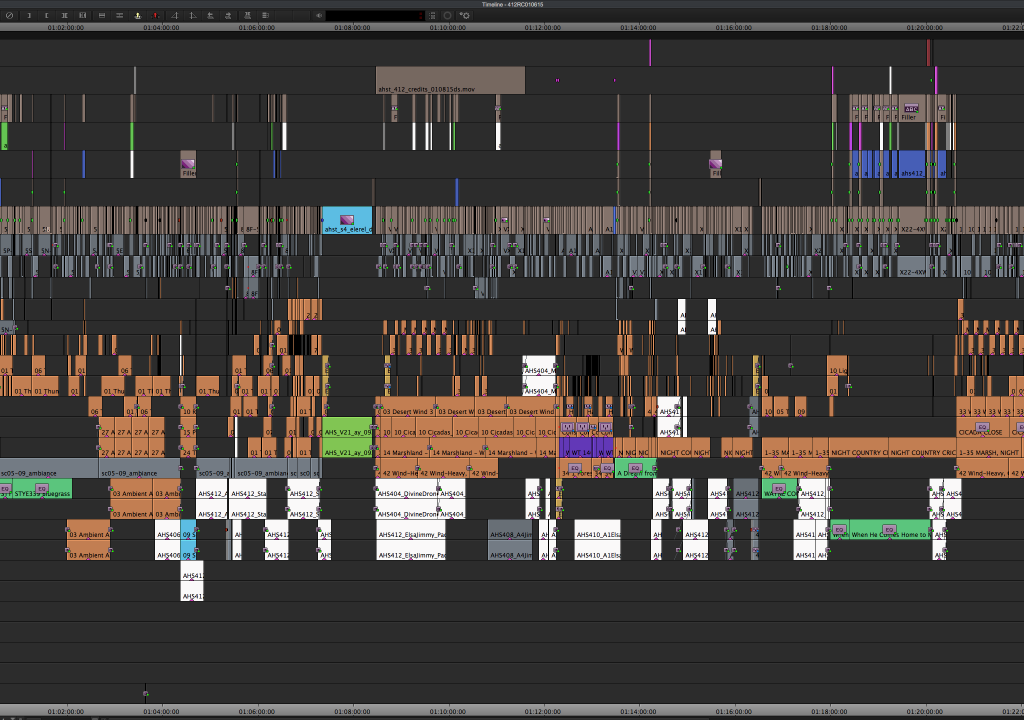

Avid timeline screenshot from first reel of Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation.

Hullfish: What are the things in Avid that you like? Have you tried other NLEs?

Hamilton: I have used Avid and I have used Final Cut 7. I did two movies on Final Cut 7. I got used to it. And I liked the subframe audio keyframes, which they still don’t have on Avid. But there are several things I really like on Avid. I’m not sure about Premiere, but the thing that was certainly a problem in Final Cut was not being able to move projects from one computer to another. The way that the Avid media is structured, if you don’t use AMA links which I never do because that way lies madness. I always transcode anything that comes in so it’s transcoded to an Avid codec and stored in the Avid MXF folder structure. If you have an external drive with the media on it, and the project, you can plug that into any other Avid on the planet and everything will pop up and nothing will be off-line, whereas with Final Cut, because you’re dragging files from anywhere you try and move to another system and you’ll find that half of the media is off-line. And so that was always a massive headache. The other thing was that everything was stored in one file. The entire project was in one file, so if it got corrupted you would lose EVERYTHING. Whereas with Avid every bin is a separate file. When you’re working on a gigantic project, the file sizes start to become enormously cumbersome on Final Cut. The only other thing is collaboration. The way that Avid allows multiple people to collaborate on one project (with ISIS) has been bulletproof for years and continues to be the market leader when you have a lot of people who are on the same media and need access to the same bins and it allows only certain users to right to bins and locks everyone else out and then the way the ISIS connects to CAT-5 or CAT-6 cables allows everybody to read everything, including a laptop if you want to. I haven’t used Premiere for years, so all of the massive advances that Premiere has taken since then I can’t comment on.

Hullfish: You were talking about being meticulous and that isn’t just about organizing but about cutting I’m sure, and a frame matters. So what about trimming tools?

Hamilton: The trimming tools in Avid are phenomenal. I have no problem keeping stuff in sync. I tend to lasso my trims, which is pretty nerdy, but if you drag a window around all the tracks where you want to trim which can be kind of higgledy-piggledy – not necessarily in a vertical line down the timeline – then Avid can make a complex trim with many tracks very straightforward. There are so many keyboard shortcuts to trimming which I use all the time. If you want to slip a shot you don’t even go into trim mode. You park on it, select the track to slip and press the slip keys at the bottom of the keyboard. It makes you look like a wizard because suddenly the music edit is fixed or you’ve just adjusted a shot by 8 frames at the touch of a button. The only thing I wish Avid would do is remove the SmartTools or have the option to remove them because they take up a lot of space on the left of the timeline. But that’s a super nerdy request which I’m sure they will address at some point.

Hullfish: There’s pacing within a scene, but there’s also pacing – kind of macro pacing – of the entire movie. And I think that the pacing changes when you see it on the big screen or with an audience.

Hamilton: I’ll give you my pet theory. One of the things I did at university was a Psychology degree. I did not go to film school but I studied visual perception and audio perception and so I have a background in this kind of stuff. And my theory is this: when you go in to a theater, it seems kind of obvious but not many people say it out loud, so it doesn’t occur to many people, but when you go in to a theater you are sitting in a dark room watching a very large image projected and your entire field of vision is taken up by the experience of watching the movie and all you’re hearing is the sound from the movie, which can become a very emotional and very immersive experience and your entire brain is focused on processing the images and the sound. And because that is all that you are doing you process them faster because your entire focus of perception is drinking the images and the emotions off the screen and taking the story from the sound and the emotions from the music, therefore images on the big screen seem slower because you are more attentive to them, if that makes sense. When you are watching a smaller screen you have multiple distractions of your mobile phone and somebody walking up and down the corridor outside and your timeline next to you which you may be glancing at, so ironically, you are less focused in the edit suite unless it’s a really large screen and you turn off your editing monitors. So that is why I feel that when you watch your movie on the big screen it seems slower.

Hullfish: How else do you think your psychology training has helped you?

Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation Avid timeline of the entire movie.

The opening sequence of Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation is a scene where Tom Cruise jumps on the wing of an A400 aircraft and takes off because there are some chemical weapons that are inside that he has to stop from reaching their destination. I watched it with an audience in our first test screening and I realized that the first two or three minutes of the scene I had slightly over-trimmed and it was running a little bit fast and the audience wasn’t quite engaging with the story. I didn’t feel it watching in the cutting room, but with an audience I felt like “This is going too fast and I’ve over-cooked this.” I didn’t even mention it to the director. I just went ahead and allowed the scene to breathe ever so slightly so that stuff landed for the audience a little more. So all the information that they needed was just given to them a little bit slower and then the next time we watched it, it just completely worked and it was because I was really carefully paying attention to how they were reacting second by second through the opening minutes of the film and I felt that I needed to address it.

Hullfish: What gave you the clue that you were going too fast instead of too slow?

Hamilton: Well, I could sense that they were not engaging in the story and not understanding what was at stake and what was going on or why certain things were happening because there weren’t audible reactions or chuckles to certain things. You know how you can tell if the audience is enjoying it.

Hullfish: Oh yeah. Definitely.

Hamilton: People were just looking at the screen concentrating and they weren’t relaxing in to it. They weren’t having their hand held enough. They were being dragged forward. I wasn’t walking alongside them, I was kind of pulling them forward and therefore they were having to do a little too much work. And I’m talking about maybe a total of maybe six or seven seconds added over the first two minutes. And it just made all the difference the next time we watched it. It landed and everything worked, so I’m constantly aware of that when I’m watching the movie with an audience, literally every minute of the film, I’m acutely aware of the reactions. There’s one place where we got a big laugh, and then Tom Cruise’s line came in too quickly so I added an extra 18 frames of a beat after Simon Pegg said his line and the laughter had died down just enough during that two thirds of a second where the audience could pick up Tom’s line. That made all the difference. So I’m always paying attention to that when there’s a new fresh audience. And this is an audience of probably 400, so it wasn’t 20 people or 50 people, but 400 people in a big theater and I was sitting in the middle of the crowd.

Hullfish: At one of the large screenings for War Room (which I co-edited and was the Number 2 movie in theaters this last weekend) I actually didn’t sit in a seat at all, but watched JUST the audience instead of the screen.

Hamilton: Interesting. I don’t think I do that, because I’m still refining the edit in my head as I go, so I kind of like to do both.

Hullfish: One of the other things with the macro pacing of the movie: with War Room, we jockeyed some scenes out of script order so that we could get the audience dialed in emotionally earlier in the movie.

Hamilton: That is what we do constantly, from the moment we watch the first assembly of any movie I’ve edited, we are constantly thinking of ways to improve the flow of the story and the way the audience engages in the story. We had a few casualties on Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation where we felt there were similar story beats in scenes, so we lost one of the scenes. There was a whole eight minute section in the middle of the film that we completely removed and during our two days of pickups we shot a new scene which allowed us to remove that chunk exactly where it needed to come out, because we were getting notes from the audience that the film slowed in the middle (which films often do) so we removed those eight minutes and the notes went away. Also, we removed some scenes with the villain and it helped make him more mysterious and slightly more threatening and people had less confusion with his motivation because he was more elusive which helped us. A lot of editors have a system of 4×6 scene cards on the wall, a series of cards running down on a white board with magnetic tape on so we can swap the cards around and see the flow of the entire film right in front of us. We’re constantly thinking of ways to improve the structure of the film to make it flow better for the audience.

Hullfish: Scriptwriters often do something similar. We used the same board and scene notecards that they used when they wrote the script to go in and re-arrange the story flow and timing with War Room. Ours were on Post-it notes which I would NOT recommend… the edit suite ended up littered by Post-It notes that were not quite sticky enough.

On a film like Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation, it is a big kind of detective story, so the characters will start here and they will get a clue and they will go there and do something which takes them to another clue, so there’s a very linear path for the story to follow just because of the genre. This means there isn’t much opportunity to drastically restructure the film, but in other movies I have done a lot of work where we’ve restructured a lot of things or got to the inciting incident quicker. And I firmly believe we should leave no stone unturned. If anyone has an idea, we absolutely must try it, because until you SEE it, you cannot know if it may have a spark of genius in there that can turn out to be something great. Quite a lot of time I hear stories of people debating or deconstructing the merits of a particular idea and quite often it takes longer to discuss it than it does just to try it out.

Hullfish: Amen. And that’s one of the beauties of Avid in particular – but non-linear editors in general – is that you can give it a shot and always go back if it didn’t work better.

Hamilton: As an editor on a large movie, or on ANY movie, you are responsible for a huge investment and you must make sure you have the best film possible that exists within the dailies, and that means trying everything out. It’s a joy being able to archive every single cut of every single scene because quite often you do over-trim things to get the film down to its running time. Then you discover that some of the heart of the film is gone. So you need to go back, let the scenes breathe a little more. And quite often when I get to the end of a cut I will want to go back and look at some of the selects reels and make sure that I have all the best stuff in there, and being able to call sequences up at a second’s notice and review them calmly while you’re eating lunch or taking a breather is worth its weight in gold.

Hullfish: That’s one of the other reasons why it pays to be organized.

Hamilton: Oh … My…. Yes. I mean, we made progress so fast on Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation. We did our first “friends and family screening” eleven days after the end of the shoot.

Hullfish: Holy SMOKES!!!

Hamilton: Yup. I kid you not. Because the pressure was on. And our first big test screening was at five weeks after the shoot and we did one at seven weeks and one at ten weeks. So instead of the usual director’s cut being ten weeks, we were on our third test screening at ten weeks and pretty much locked picture. We tweaked the edit for another two weeks and then we were done. So twelve weeks of editing after the end of the shoot which is insanely fast. But because I was so organized it meant that if Chris McQuarrie suggested something, I could make stuff happen REALLY fast. Almost as fast as he could speak it. Then we could watch it and decide if it was better or not. For example, the opera sequence in Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation is monumentally complicated – as any editor who watches it I hope will see. It’s an enormous, challenging, multi-layered puzzle of music and stories and different characters and locations and geography and coverage, so many plates spinning at the same time. Trying to make it clear where everybody is and what the stakes are and why people are doing what they’re doing… It’s that great cinema storytelling thing of only giving the audience 1+1 and hoping that they’re making 2 throughout the whole scene. And that was a scene that we refined endlessly over the whole duration of the film. It was the very first shot of principal photography and the very last shot of principal photography. That sequence was shot in so many different locations and bits of sets and stuff. And it would have been impossible without the abilities of a digital non-linear system to try stuff out and throw stuff away and cut stuff and go back old versions and re-edit the music and trim a few frames here and it was really tremendously difficult, but very rewarding when it started to work for the audience. And people have responded warmly towards it now, so I’m thrilled that it seems to be working for people. It really makes it worth it.

Hullfish: Obviously you can’t really cut a movie the scope of Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation in eleven days. So what was the shooting schedule like?

Hamilton: The total number of shoot days was 127. I think.

Hullfish: I’m laughing because War Room shot in 30, which is actually a decent schedule for an independent movie.

Hullfish: The interesting thing to me is that because of the linearity of the story of the film, that eight minute piece you said was cut in the middle couldn’t just be cut without shooting something to replace it with something that was meant to be shorter.

Hamilton: Yeah. So we had shot a scene in a Moroccan bar and it led the characters down a certain path and we came back later and shot the scene again so that they went straight to London, and the story carried on from London instead of them taking a detour round another eight minutes of story. We didn’t miss it at all. It was just a very elegant solution and something which we as editors and filmmakers do constantly when we are advising productions on additional pickups. It’s how to simplify story and make it work for the audience better by shooting one extra scene which can remove six scenes. That happens quite regularly. Peter Jackson on all the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit movies did a month, two months, three months of pickups for each film to improve the story based on discoveries in the editing room. That’s very, very common and producers have usually set aside a small slice of the budget to allow for that.

Hamilton: Quite often I do. It’s not appropriate on some very confidential films, but for example on X-Men: First Class, I worked on that movie for two months before the shoot started, not necessarily on the entire script, but I was reading drafts and feeding back to the director (and co-writer) Matthew Vaughn. I was working on pre-vis, trying to solve story problems in a small way. There are a lot of people who have opinions on those big films. For example, on Matthew Vaughn’s Kingsman sequel – which he is hoping to make next year – I am going to be on board for four months of prep, working with Matthew and the other HODs (head of department – camera, art, locations, lighting, sound, post, etc.) to give some storytelling input. I think he’s hoping to avoid unnecessary shooting and discover story kinks in the way that an animated film does where they cut and review story reels, so they can make decisions about what they’re going to animate because animation is so expensive. He wants to prep the film in terms of story very, very thoroughly and try to figure out the pace of the movie so there isn’t much waste on the set.

Hullfish: I have wished for that, where I have read a script that’s already been shot or is about to be shot and thought, “this scene or these scenes are never going to make it into the movie.”

Hamilton: I know. It’s crucial and I feel that it is your job as the editor to put your hand up and tell people (if you have that sort of collaborative relationship with a producer or director), articulate to them why they’re about to spend money on a scene that’s going to hit the cutting room floor, and if you have a very good reason for it, you should speak. The other thing that is interesting is that if you are going for an interview with a director for a gig, quite often you DO get to read the script in advance and I always prepare thoroughly a comprehensive criticism of the script: where its strengths and weaknesses lie and how perceived story problems could be solved at that stage rather than in the cutting room, which is where they WILL always be solved, often at greater expense. And part of the reasons that I like to do that is that over the years I have read a lot of scripts and edited a lot of films based on those scripts, and all the problems that I felt when I read the scripts are ALWAYS there in the cutting room. And then we have to fix them and it’s normally much more difficult to fix them then or it’s a kind of a work-around or it’s unsatisfactory. And so I’m very vocal when I meet directors to explain to them what is great about their script and what could be improved. And I think that is one thing which they value enormously in an editor is a storytelling collaborator and somebody who has the best interest of the film at heart and somebody who will fight in the film’s corner regardless of schedule and budget. If I feel we need a shot I will always say “We need this shot,” and it may be inconvenient or it may cost a little bit more money, but I know it will be cheaper to do it now than to do it in six months or not to have it, in which case the film won’t be as good. Most people respond favorably if you speak up.

Hullfish: You said that your hobby or second vocation is to learn more about story. Would you recommend that editors read something like Robert McKee’s “Story” or are there resources that you think are superior for learning story?

Hamilton: I have read a lot of books on story and currently there are two books that I recommend that everybody reads. One of them is so good that I wish I could keep it a secret and not tell anybody. The first is called “The 21st Century Screenplay” by Linda Aronson. She has written a fantastic book about creative screenwriting and unlocking creative potential, but the trick with that book is the second half of it is a study of non-linear storytelling, an example of which would be Slumdog Millionaire, where you’re jumping back and forth between moments where Dev is answering questions and then flashbacks to his childhood. And she’s analyzed and has theories of why certain non-linear film stories work and why some don’t work as well. And I’ve found it incredibly useful as an editor to understand and grasp her rules of non-linear storytelling and it has been hugely beneficial to me on several movies where I thought, how can I re-structure this and the lessons I learned from reading her book gave me great insight into what might be a good solution. So that’s one book I’d recommend. The other book, which is really my favorite, favorite storytelling book at the moment, which I only read about last month, is called “Into the Woods: A Five Act Journey Into Story” by John Yorke who has spent nearly 30 years working in British television as a scriptwriter and producer. It is not a long book but it is a BRILLIANT book. So many light bulbs went off as I was reading it. And it’s only a few hundred pages compared to some of the storytelling books, which are 700-800 pages. In the appendices at the end, he has a thorough breakdown of all of the storytelling gurus, and all of the maps that they subscribe to for three act structures or five act structures or some people have eight or ten act structures, which all start with an ordinary world and then an inciting event and they’re called to an adventure and a journey and he summarizes the fact that people are giving you the same guidelines as to how to tell stories. He has articulated in the book how a hero’s journey changes from beginning to end better than any other book I’ve read and every editor should read it. It is just brilliant. And re-read it constantly because it will keep your storytelling skills really sharp. There is also a third book, which is a massive storytelling bible, “The Seven Basic Plots” by Christopher Booker which is a monumental life’s work, where he has effectively read, watched, studied, almost every play, novel, poem, song, opera, musical and film that’s ever been written through the whole of history, then taken a step back and compiled everything he’s learned and put it in a book. If you find yourself with a couple of weeks to spare, it is the most wonderful, encyclopedic journey into the world of story from the dawn of time ’til now. I absolutely loved it and was so grateful that he had done all that work so that I didn’t have to. But John Yorke’s book “Into the Woods” distills that even further and he has read ALL the storytelling theory books. Many more than I’ve read and his book is like a “greatest hits” of all of them. And the reasons WHY we tell stories. There’s a lot of these books that explain the mechanics of story but don’t really explain WHY the mechanics of story have ended up working for human beings. Why children can write stories at age five that follow a basic three act structure when they’ve never been taught it, and he spends quite a bit of time in the book investigating human psychology and philosophy, why human beings need stories and why we tell them in the way that we do, and it’s so important that we as editors understand that stuff because it’s our bread and butter.

Hullfish: That is fantastic advice. I love story myself, so I’m excited to get those resources. I was hoping you’d name three books and I would impress you by saying “they’re all on my bookshelf,” but you surprised me.

Let’s switch the conversation to pacing and rhythm. In my interview with the editor of Gravity, I mentioned that I’d edited some animation myself, and the editing on animation is really done BEFORE the animation is created. And when I saw that opening scene of Gravity that’s 12 minutes long in a single shot, I said, “That had to be edited – even though it’s one take.” And I felt the same way about the big Colin Firth fight scene in Kingsman.

Hamilton: You mean the one in the pub?

Hullfish: There’s a musicality or a pacing that is just great. Time speeds up and slows down and the sense is of something that isn’t even edited but almost danced. Talk to me about what was done either before the scene was shot – or after – to create that pacing and flow and rhythm.

Hamilton: Absolutely. The way that Matthew Vaughn likes to shoot action if he can is a Hong Kong method of shooting, where every shot in an action sequence is what’s called a “special” shot, which just tells a very, very specific beat of story. Quite often when fight scenes are shot, you shoot coverage of a fight. So the stuntmen do it several times and you shoot a wide and you shoot overs and close-ups and you MAY shoot a couple of “special” shots, for example, someone reaching for a knife or a stab or something, but generally you’re shooting coverage. The Hong Kong way of doing it is that every single shot is a special shot. And those sequences are refined and refined and refined on video cameras with the stuntmen in a room full of pads for weeks before we have an approved fight which the director has signed off on. Now, they’re quite often a bit longer than they’ll end up being in the film and quite often they’re very ambitious, and then the practicalities of shooting with an ARRI Alexa or a Panavision film camera are different to using a little video camera, which is one of the pitfalls of using this method, but everything is planned meticulously beforehand and you go in to the shoot knowing that you have to shoot 60 shots in five days to tell this story. And for those scenes, and for the scene in the pub with Colin Firth, and for the scene in the church – that seriously is a one take shot. Months of planning. And I was there on the set cutting as they shot the sequence so I could advise them as to how the shots joined together and certainly for the church scene I would join the shots live as they would film and check that the invisible joins would work perfectly. And then for the pub scene I spent five days on the set. I would suck the video off the video assist and AMA them into the Avid, transcode them and cut them immediately. Seconds after they’d call cut I would have the slate on my timeline and I’d be cutting it in and trying stuff out, so those scenes are very, very carefully planned, which is why you feel that as you watch it. That’s what makes them so unique, because they’re really hard to do. You can shoot a fight scene in a few hours with a few stuntmen fighting and you shoot coverage, or you can spend five days make it really eye-catching and memorable and fun and fresh, which is what Matthew Vaughn likes to do. And that is why on the Kingsman sequel I’ll be working for four months on those complex sequences before a frame of film is shot.

Hullfish: Now the big danger, it seems to me that in shooting that Hong Kong method, if you do want to cut out an action or two, they’ve been planned to flow into each other.

Hamilton: That is true, so what happens is that quite often you’ve got a spectator. In the pub scene, Eggsy is watching to the side and so if we wanted to truncate a bit of action, we could cut to him briefly watching and then go back in to the story. For the church scene we could cut away to Samuel Jackson watching on his computer. And we did actually remove a very, very intensely violent section of that fight which was too much even by our standards (and the film is pretty intense). There was a bit where people were like “That was too much.” So we removed that 20 seconds of it and there were ways where if we do a whip pan from one side of the church to another, anywhere in the whip you could join to another whip pan and find yourself in a different part of the fight. So there are certain little exit strategies you can use if you want to change it, but generally speaking you have worked for months to plan it carefully, so hopefully you’ve made all the right decisions and you’re not backing yourself into a corner.

Hullfish: One of the things people are amazed at when I tell them is the shooting ratios of the films. What do you think the shooting ratio for Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation was, and then for maybe just a complex action scene.

Hamilton: I have not got an accurate footage count for Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation but I would estimate about 1.5 million feet of film. Maybe more. Roughly. Around about 250 hours, 300 hours. Maybe not quite that much. Shooting ratio is at least 100 to 1. And one elaborate sequence, for example the motorbike scene in Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation which works for a lot of people, and I’m thrilled, but it was an enormous challenge to get there in the cutting room. We had about 12 hours of footage for a scene that is about 2:40 in the film (a shooting ratio of 2700:1).

Hullfish: What do you do to try to cut that down? I remember on Courageous I maybe had 2 hours of a climactic gun battle that ended up getting cut to 2 minutes in the final film. How are you approaching that process? I started with piecing together the mini story of the battle and then amplifying it with better pieces as I found them and then culling it back down from there when I had about a ten minute sequence. How do you make sense of 12 hours of footage?

Avid editing timeline for the final reel of Kingsman: Secret Service. Note the named audio and video tracks and use of clip color coding.

Hamilton: Well, there are no shortcuts. I had a similar situation on the skydive sequence in Kingsman. 15 hours for a scene that runs about 4 minutes in the film. You have an idea of the story you’re trying to tell. What I do is watch all the footage and anything that might be useful, I stick it on a timeline in rough story order. I use Clip Color in Avid in the sequence, so I’ll color the subclips based on the part of the story, or the character, so that I start building up a rainbow of color so I can see how much of each character I have. For example if one character is orange and another character is green and another character is blue. And then what TYPES of shot, so the wides, the mediums, the tights all go on different layers of the timeline. I go through and watch everything meticulously and I put it in rough story order regardless of how long it is, so I may get the 15 hours of skydiving in Kingsman down to about an hour and forty minutes. Then you watch and refine and throw out even more and you get it down to 40 minutes and then you keep going and you get it down to 15 minutes. It’s the process of slowly, slowly, slowly figuring out what is the best footage that exists to tell the story and then starting to build the sequence and working out the most interesting juxtaposition of images and the pace and energy of the scene, and allowing certain shots to breathe, and certain shots to be more exciting and quicker and shorter, and make sure the audience understands the stakes of the action sequence, and the geography of it, and why the characters have to succeed or fail. That is crucially important. If the audience doesn’t understand what the characters are doing in the action sequence or what their goals are or what the repercussions are if they fail, then there’s no emotional attachment and people will just disengage, so all of that stuff is critical to set up and then keep an eye on. It’s a very long process of refining the sequence until you get it, and I’m always working with no music or sound effects. I’m imagining everything, and then later I slowly build up a fairly detailed soundscape of atmospheres and sound effects and vocalization and dialog and then I’ll build the music and start to feel it, and continuously refine allowing all those different elements to feed in to the story. Quite often, when the sound goes on, the scene can get even tighter because the sound does some of the storytelling for you.

Hullfish: I have the same advice for editors. The thing’s got to work without the audio. It’s definitely got to work without music and beyond working without music, a dialogue scene needs to work without hearing the dialogue.

Hamilton: I wholeheartedly agree with you. Cinema is about making the audience do the work so that they engage with the story. Television does that to a great extent now, but back in the day television spoon-fed you a little more and was easier to watch. Now it’s completely different but pure cinema in theory should be silent cinema. Human beings are “meaning-making machines” and their survival is dependent on building meaning from what they can see to tell a story. We will all try and build a story in our head with anything that we see. An audience loves being given one plus one and then coming up with two on their own. I believe that’s from Andrew Stanton’s TED talk.

(https://www.ted.com/talks/andrew_stanton_the_clues_to_a_great_story?language=en)

So they love to see a close up of an actor and a shot of what they’re seeing and they’ll try and connect the two. We’re not telling them what it is, we’re asking the audience to make the connection for themselves, and that is pure cinema. So what you’re saying is that story should absolutely work without dialogue and without music and without sound, because the emotion inherent in the performances should be enough for you to start understanding the scene.

Hullfish: You’re talking about emotion and that brings me to one of my other points. I think part of my job is to – well, not manipulate the audience’s emotion, but definitely guide or push them – maybe manipulate is the right word…

Hamilton: Manipulate is exactly the right word.

Hullfish: Is your psychology degree a help to you in manipulating the audience’s emotions?

Hamilton: Not really. I think it’s just experience. It’s living life and being aware of what is going on around you and understanding how your own emotions are being manipulated.

Hullfish: Give me an example of how – in one of your movies – Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation would be best – how the audience’s emotions are being manipulated.

Hamilton: Well, you’re manipulating the audience’s emotion with every cut by what you are choosing to show and how long you are choosing to show it. It’s what we do as filmmakers. It’s filmmaking. There isn’t really an example. It’s the whole movie. You can watch any scene and you can see how you’re being manipulated. Some people take offense to using that word – manipulation – but the simple fact of the matter is that audiences buy a movie ticket to have an emotional experience. And they’re choosing the kind of movie they want to see to have that particular kind of emotional experience. They’re choosing to see Sinister because they want to be scared, or they’re choosing to see Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation to be engaged with the action and plot twists, or they’re choosing to see Jurassic Park because they want to be thrilled by dinosaurs. And when they don’t have their emotions manipulated they feel like they haven’t got their money’s worth. So our job as editors is to start at the beginning of the film and figure out how to manipulate people on a shot by shot basis. And then on a scene by scene basis and then over the duration of the entire movie. An example from Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation would be the choice NOT to put music on a suspense scene, that was a way to manipulate the audience because you’re not giving them the easy reassurance of score. You’re not telling them how it’s going to end. You’re playing the scene out bare. This is the scene in the middle of Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation where Tom Cruise is underwater and the sound effects play for several long minutes. And the audience is confronted by the reality of the situation. They’re holding their breath too. You can hear a pin drop. Then we, as filmmakers, chose to start the music at a point in the sequence where we wanted to dramatically increase the excitement of the scene and when you see the film, you’ll understand what I’m referring to. Another example of how we manipulate the audience (and it’s right at the beginning of the film) is where we start by teasing the Mission: Impossible theme very lightly, “Remember this cool music that you used to love when you were younger? This is the kind of cool stuff you’re gonna get.” And then we don’t play it. We save it until the opening credits which come three or four minutes later. We just tease you. We’re just going to tickle you a little bit but we’re not going to give it to you yet. We have a terrific music cue playing and we get the characters who are all trying to stop this plane from taking off, and they’re going to fail and just as all hope is lost Ethan Hunt appears and manages to get on board the airplane, and then there’s some humorous stuff where they’re trying to get the doors open and it’s great stuff and we know that’s humor and we want the audience to laugh there. And there’s a terrific end to the scene which is very funny and entertaining, and then we blast into the opening credits and we have a very stylish and fast cut opening title sequence which is telling you, “this is going to be really great fun guys, and there’s cool gadgets and there’s all these great actors that you’ve seen in the other Mission: Impossible movies and they’re all in this one” and that’s how we’re doing it. We’re choosing how to manipulate everybody second by second through the film.

Hullfish: I deal less with action and more with drama and for me the reaction shots manipulate and show emotion…

Hamilton: Yes. Absolutely.

Hullfish: I’d actually love to experiment with a cut of a scene where I’m never on the person speaking.

Hamilton: Yeah. But the problem with that…

Hullfish: … That it’s a dance.

Hamilton: No. It’s not that. The problem is that there will be certain pieces of information that are key to the story of the film, and audiences do not pay attention when it’s playing on a reaction shot.

Hullfish: That’s interesting.

Hamilton: They’re paying attention to the emotion of the character who is hearing the line. But if you want a specific piece of information to go in to the head of the audience, it’s a pretty safe bet that you should play it with the character saying the line on camera if it’s something that is really crucial. Like for example, “You have to drop the photon torpedo into the exhaust port of the Death Star to blow it up.” If you’re playing that piece of information on Luke Skywalker listening you won’t understand when he’s getting to that point and he’s got to get the photon torpedo down the exhaust port of the Death Star. The crucial piece of information will not have landed for you and you won’t understand what he’s doing, so in every dialogue scene there will be something which is important for the audience to take forward to the rest of the story and so my initial response to just playing it on reaction shots is that something will be missed, and some crucial piece of information will not land properly, and therefore it will cause a story problem later in the film. That’s just my two cents.

Hullfish: On the last film I worked on I was impressed with the speed that the professionals on the set recognized which ones were the highest quality interns. It was apparent by the end of the first day which ones you wanted to work with and which ones you did not and I think it was all about attitude more than talent.

Hamilton: Yes. I would agree with that.

Hullfish: What would you say about the attitude you have to have, the curiosity, the passion, the social skills… what draws you to someone when you say to someone “I will take you on as a trainee or as an intern. I will let you be my assistant.” What is it that makes them desirable?

Hamilton: I will tell you. I have to make this decision a lot. I try to meet everybody who emails me. I may get two or three emails a week politely asking if I would meet them or give them advice and I always try to meet them in person if I can, in fact all of my assistants I have discovered this way. And the people who have taken the time to find out how to contact you and then write a polite, articulate, correctly spelled email with a well designed CV which has a sensible file name for the PDF, and doesn’t just say “CV.PDF” lots of little tiny things like that, and then you meet them, it becomes very clear if they understand the realities of the film industry which are sadly that film school gives you no professional experience so you are starting in exactly the same place as anyone who has NOT been to film school (which is: with no industry experience), and you need to start at the bottom and prove to people that you are going to be trustworthy and reliable and work hard, turn up early, leave late and do any task, however menial, with a smile on your face. And learn the industry from the inside because it is very different from anything that you would have learned in film school. Some people have that attitude, and they are so excited to be there and see the process of editing a movie, seeing it come alive, that they really want nothing more than to be part of it, and make the tea and get lunches and if they’re lucky, import sound and mark up dailies and export QuickTimes, but nothing they will have experienced before will have prepared them for the realities of a feature film cutting room. So I know very quickly if people have done their research. I expect them to know a lot of technical stuff. There are a lot of resources out there to learn about the difference between the RED camera format and the ARRI ALEXA camera format. You can read that in half an hour on Wikipedia if you choose to do that. And editors need to know that, it’s just a fact. To be honest I won’t employ anybody as a trainee unless they’ve done usually at least two years of being a runner in some sort of post-production facility, and then made mistakes and learned the hard way about how not to screw up, which is so important on a film. There can be NO mistakes made in editorial. Nothing can leave the editing environment that hasn’t been checked and is 100 percent accurate. And those people need to have made those mistakes in another environment and realize that they need to check their work and take pride in their work.

Hullfish: That starts with that email. Spelling. Proper file names. A level of attention to detail that starts with the very first impression.

Hamilton: Totally. I get an impression straight away. Other things that help are if somebody comes to the cutting room and bring pastries for the assistant editors. That certainly leaves an impression and has worked in the past for people. One of the things I did is send a Kit Kat with my CV because it’s slim and it fits in an envelope, and when people get a Kit Kat they may not like chocolate or they may not want the calories, but it certainly leaves an impression, and they can give it to their kids or whatever. And they say, “Oh yeah, that guy sent me a Kit Kat. That was unusual.” But generally speaking I’m looking for attitude, for the ability to put in the hours, constantly asking questions and being proactive about their learning…

Hullfish: THERE you go.

Hamilton:… and being excited about being given opportunities. When I started out as the runner at a post production facility, I stayed there every weekend learning every piece of equipment until I knew everything about how everything worked. I knew every DigiBeta. I knew every BetaSP, I knew the inside of the Mac Quadra that was running the early Avid Media Composer. I knew how to use off-line suites and on-line suites. I knew about EDLs. I just had an insatiable thirst for every single tiny piece of technical information and I just wanted to be the best. There wasn’t really an internet, there certainly wasn’t Wikipedia. But I was in an environment where I could learn and there were people who were very happy to teach me if I took the trouble to politely ask them how to do something. And I would do my own projects in the evening and when someone got sick one day, I could say, “You know what? I can do that. I can use a Media Composer and I can cut this show for you. Even though I’m a trainee, I can do it.” And someone gave me a shot and I could do it and I was thrilled to be given the chance to do anything. And I worked my way up that way. And I’ve never stopped having an insatiable desire to learn everything about the film industry and I unashamedly want to become one of the best in the world at what I do, and that means constantly educating yourself on a week by week basis on the trends of the industry and new technology and about best practices for how to work in a cutting room. I must have done 50 or 60,000 hours on Media Composer over the last twenty years and I’m still learning something every day. I pick up little tips and tricks and you never stop learning and that’s part of the process as well. I’m always asking myself how I can do the job better and faster and more efficiently, how I can make the pipeline easier and smoother and I always challenge received wisdom. I always ask myself, “Is there a better way of doing this.” Because a lot of people still work at 23.98 or 23.976 timelines and there’s just no reason to do that anymore, because the only reason that 23.976 existed was to downconvert to NTSC at 29.97 and nobody uses NTSC anymore, and so there’s no reason to shoot at 23.976. Everything should be shot at true 24. And I remember making that case to post supervisors and they were going “No no no no no! We do it at 23.976.” And I’d ask, “But why? What framerate is the DCP? It’s true 24. Why don’t you shoot at 24, cut at 24, post at 24 and then the DCP is made at 24? And when you create a 23.976 master, you do it at the end. Everything is much easier that way. The best way is to shoot the same way the audience will see it in the cinema which is true 24 frames per second. Every monitor on the planet can play any frame rate now, so really, just an example of one of the things where I was making the case for 24fps years ago when HD started coming out and nobody was bothering with NTSC DVDs and everything was on-line or on QuickTimes. That’s just an example of where I said, guys, we should be doing this differently.

Hullfish: I had never considered that. I just shot a project at 23.976 yesterday.

Hamilton: I can’t see a reason to do it. 23.976 is a standard definition legacy thing. It’s a pain in the ass for everybody. On a professional level film, you should be shooting true 24.

Hullfish: Same as drop frame and non-drop. Same thing. I love that you challenge the conventional wisdom.

Hamilton: Constantly. If there’s a better way of doing something. I always say to my assistants, the way I do things is how I’ve evolved the best way of doing it over 20 years, but it may still not be the best method. If you have a better way of doing something, please tell me because I want to know. And you guys may have experienced something on another film which I haven’t, like for example labeling the bins with the slates that are in each bin. I used to just do scene 40, part 1, part 2, part 3…but I wouldn’t know what slates were in each part. Then one of my assistants said, “If you just labeled them A – G you would know that slates A – G were in that bin. And they’d still sort chronologically since the next bin would be H – M.” And I was like, “That’s a great idea.” And I only did that for the first time on Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation.

Hullfish: I’ve been editing on Media Composer since 1992 and three or four years ago I had an assistant that did something and I was watching her and I said, “What did you just do?” and she showed me and I was like, “I had no idea Media Composer could do that.”

Hamilton: I really love it when that happens because I think I’ve learned something new and I’m better at this job than I was yesterday. I really dig that. It’s cool.

Hullfish: I thank you for your time. I’m excited to see Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation. Hopefully the readers will be as well. Thanks for your insight into all the great stuff you talked about: Story, pacing and psychology, workflows, getting ahead in the business and all of that. Especially that editors need to know the theory of story just as well as a scriptwriter does.

Hamilton: Totally. Thanks so much.

Hullfish: I’d love to send you a copy of my latest book, “Avid Uncut” as a thank you.

Hamilton: I’ve already read it. It’s a terrific book and everybody I know in the industry has read it. Like all of us, I try and absorb as much as I can. I’m a total nerd so any time where there’s cool stuff I can learn from other people I’m all for it.

To see the other interviews in this series, please check out the Art of the Cut page: https://www.provideocoalition.com/tag/art-of-the-cut