Pop Quiz: What Am I?

An invention dating back nearly half a century has now been popularized, an invention that has already changed the world. It has revolutionized the way we communicate; we can now send rich messages to millions of people across the globe faster than ever before. And it is increasingly our number one source for news and many other types of information.

However, most efforts at truly native storytelling using the technology have been less than compelling, and there has been a lot of resistance to change by the entertainment industry.

What is this invention? __________________________________________________

Must be the Internet, right? … Indeed it is!

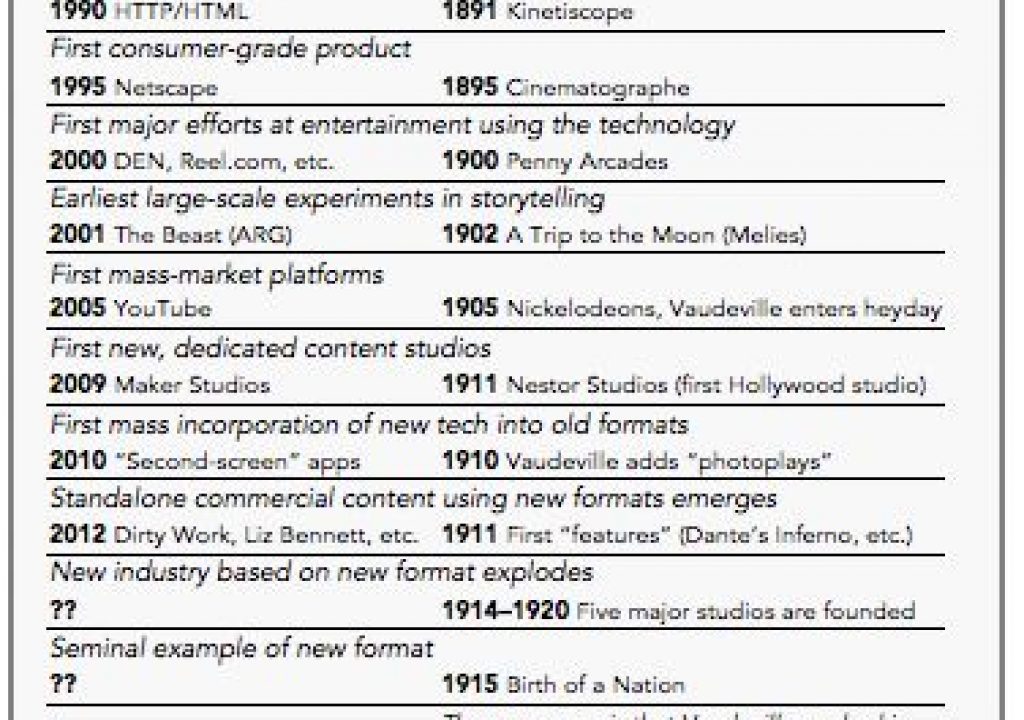

However, the statement above is just as true of the motion picture camera in 1913. In fact, there are many, many parallels between the rise of the movie camera and the Internet, eerily spaced almost exactly 100 years apart:

OK, why does this matter?

Well, if you have any stake in the entertainment industry, whether you’re the CEO of a global media conglomerate or just an enthusiastic media consumer, it should be of interest to note that we are tightly paralleling the track of another major transition in entertainment, when a new upstart called “the movies” upended the stage play/Vaudeville industry and went on to generate trillions of dollars in revenue over the next century.

History does repeat itself; history is repeating itself, and if it continues to do so and you work in the entertainment industry… RUN FOR YOUR LIVES!!! The proverbial fan is about to get hit with a huge, existential bag of shit.

Vaudeville

In the early 1900s, Vaudeville was largely a reaction to increasing levels of disinterest in stodgy formats such as classical stage plays and musicals. Nickelodeons (pictured below) had whetted the consumer appetite for shorter and more exciting forms of content.

In reaction, theater companies created variety shows consisting of short bursts of comedy, drama, music, dancing, juggling, burlesque, magic, and eventually “photoplays.” This was Vaudeville, a ‘platform’ that supported a vibrant, exciting industry, with thousands of traveling troupes of performers, many of whom were amateurs.

Fast forward to today… People now, particularly younger ones, are increasingly disinterested in stodgy formats like television. The Internet whetted their appetite for shorter, more exciting and more relevant content. And like Vaudeville, YouTube built an enormous platform around this demand, a platform that is incubating a new pool of talent, many of whom are starting out as amateurs.

In short, YouTube is fundamentally a massive variety show like Vaudeville was, but instead of slapstick we have Fail videos, and instead of Milton Berle we have Ray William Johnson.

So what eventually happened to Vaudeville? Well, the format was good for moments of emotion and excitement – a laugh, a cry, some titillation – but it could not match the depth of storytelling and emotional connection of a great play, or ultimately, of the movies.

Today, YouTube content similarly suffers in comparison to TV. YouTube is perfect for cat hijinks and car wrecks and emerging personalities, but so far it has not produced great storytelling. We have yet to see I Love Lucy or The Sopranos for YouTube. This doesn’t mean that YouTube talent is incapable of telling great stories (in fact, the greatest stars of the 20th century started in Vaudeville), but the context and format of YouTube video make retaining audience attention sufficiently very difficult.

Happens Every Time

Of course, we should be careful about placing too much predictive power into just one historical parallel. Let’s look at a few other major media transitions to see what patterns we can find…

This chart represents the wholesale disruption of the movie industry by television, which was then a new format driven by an emerging, powerful distribution technology. As the TV format matured in the 1940s and TV sets became widely available, the disruption happened ruthlessly and rapidly. Within six years, TV was in 50% of homes and had reduced movie ticket sales by half. In fifteen years, TV was in virtually every home and movie ticket sales were down 80%, a level from which they have never recovered.

The coming disruption will happen much faster than that. The rate of technology change is accelerating and time-consuming physical infrastructure challenges have largely been solved, i.e. the equivalent of the “broadcast towers” and “television sets” of the 21st century are already in place.

Music

OK, we all know what happened to the music industry, but why did it happen?

What’s important here is not just that this is yet another example of a huge, rapid media industry disruption, but also of how crucial format is to the process.

Of course, the emerging process of digital downloading was the key catalyst for this disruption, but the other reason that iTunes stole the music industry’s lunch money is that Apple allowed the format of the music itself to evolve while the incumbents resisted the change.

As we see in the chart above, we didn’t just replace albums with digital albums; we moved most of our consumption to singles. Why download an entire album worth of songs when you really only want that one song your friend played for you the other day? The album format was a result of the economics created by physical media distribution. When the distribution was changed to digital, the old inefficient album format was no longer necessary.

Television is no different. Why watch a broadcast at all anymore? Why wait a week between episodes? Why require a 30-minute minimum or a 60-minute maximum for a show? These format restrictions are purely left over from a broadcast model dictated by physical infrastructure. And just like the album, the 30 or 60-minute TV ‘show’ is becoming as obsolete as rabbit ears.

Newspapers

In this case, what’s remarkable is not just that newspapers were the latest victim in our Timeline of Tragedy, but just how quickly it happened and how colossally unprepared the industry was.

To get a sense of how stunning this blunder was, watch the video below:

http://www.wimp.com/theinternet/

Yes, they were going to deliver online newspapers thirty-two years ago! This whole Internet thing didn’t just sneak up behind them in the night.

So how do huge, century-old, seemingly well-run companies like the Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, and Tribune, plus scores of print publications like Newsweek, Variety and others fail to take action until it’s too late? It’s called the Innovator’s Dilemma, and it happens every time.

Sure, some of these brands will survive, but be assured that the Washington Post getting bought out for relatively pennies by the dot-com book guy was not the glorious legacy the Graham family had in mind.

Yes, Virginia, TV is Dead

OK, you’ve…

heard it all before for the last twenty years people have predicted the death of TV but it’s never happened and the ratings are stronger than ever and ad prices are rising year-over-year and television shows have never been better look at Breaking Bad and we also have new distribution channels like Netflix Hulu Amazon changing the model look at House of Cards and Youtube will take over and it will be a gradual change not a sudden one and the big agencies still spend money on TV and the media buyers will never let it happen and um and and…

Now, let’s take a deep breath and really look at the situation today…

- Nearly every consumer behavior relied upon by television to feed its business model has changed. No one, statistically speaking, sits on their couch and watches live television with commercials anymore.

- Multitasking, time shifting, and ad skipping are already ubiquitous and quickly becoming universal.

- Brands are moving their ad dollars away from television.

- Pay-TV is hemorrhaging subscribers.

- The average broadcast television viewer is nearing retirement age.

- And in the meantime, industry conglomerates are squabbling about who gets the window seat on the Hindenburg.

There is an oft-quoted line, paraphrased here:

The only people who watch commercials are the ones who can’t figure out their DVRs.

The chart below represents the corporate equivalent:

The only companies who pay for TV commercials are the ones who can’t figure out the Internet.

When the cost of a Thing goes consistently up (here, ad prices), and the value of that Thing (here, ratings) goes consistently down, there is an imbalance in the market. All such imbalances correct themselves eventually. The value of the ads has to rise in order to catch up to the prices, the prices have to fall, or the product itself has to evolve.

In this case, the imbalance exists because brands and agencies don’t think they have a viable alternative to TV ads, so they have no choice but to pay the prices the networks charge. Despite the huge volume available, brands will pay very little, if anything, to sponsor YouTube content, because they have no confidence that YouTube is delivering quality consumer engagement. Also, the big players involved in this market are motivated to insert as much inertia into the process as possible – because it’s still true that no one gets fired for buying a 30-second spot.

The missing piece to correcting this, and the greatest opportunity, is working out a new format for Internet entertainment that will give brands the confidence that consumers are engaged and attentive, and that their ads aren’t being run next to “Teh Ultimate Beer Bong Fails 2011.”

So, What Next?

Hopefully a good case has been made that there are strong precedents to learn from when circumstances line up as they are now. So let’s go out on a limb make some predictions:

- We are on the verge of a major new entertainment format brought about by a fundamentally new distribution technology (the Internet).

- Many of the new players enjoying huge audiences today (YouTube, Hulu, Netflix) are transitional and may or may not end up long-term winners.

- Traditional entertainment formats will not disappear but will be radically smaller by the end of this transition.

- Many incumbents (studios and networks) will not be able to adjust and will go out of business or be acquired for a small fraction of their current valuations.

Sounds dreary, right? Is there any good news to take from all this? You bet!

In 1915, with Vaudeville at its peak, the film industry began to combine all of the “gimmicks” born in nickelodeons (special effects, editing, etc.) with a new crop of storytellers incubated by Vaudeville, and the art form of the movies came into its own. Birth of a Nation, in 1915, despite its atrocious subject matter, was a landmark achievement – arguably the first film to really show how powerful storytelling in this new format could be.

At this point, as the stage play industry began to fade, and Vaudeville slowly disappeared, the next 5 years ushered in most of the major Hollywood studios that still exist today (Warner Bros, MGM, Fox, Universal, and Paramount). Collectively, these companies have generated trillions of dollars in revenue over the last century. That’s the opportunity today; those are the stakes.

Alternate reality games, transmedia, viral marketing, second screen apps, augmented reality, and countless other experimental forms of Internet storytelling are this century’s equivalent of the nickelodeon, a bunch of techniques that, in isolation, are gimmicks but as the building blocks for a new, integrated storytelling format, represent the shape of things to come.

In order to really get a new industry started, we also need to learn to declare victory when something does work, instead of reinventing everything all the time. We need efficient distribution, we need a common language, and we need investment to help formalize this new format and scale the business.

This is all easier said than done, of course… Let’s pretend we have one brief trip in a time machine to 1913 where we can go back to try and convince our great-grandparents to invest in one of two companies. They can choose either Frank Karno’s Vaudeville Troupe starring Charlie Chaplin, playing to packed houses around the world and practically printing money, or the struggling Zukor’s Famous Players in Famous Plays Film Company thrashing about trying to make a living with “photoplays”…

We think this new gadget is interesting, kid, but it’s just a fad. Vaudeville is here to stay and Charlie Chaplin is the bees knees…

Now try pitching a VC on platforms and content that look beyond YouTube MCNs and you’ll often hear the same message with different nouns.

Very interesting technology, but it’s still too early to monetize this. It’s still just a gimmick and way too risky for us. Just look at the numbers, YouTube is clearly going to be the dominant force for a long time to come.

Of course, Frank Karno went bankrupt in 1925, and Adolf Zukor founded Paramount Pictures in 1916…

If history teaches us anything, it’s that history can teach us anything. If we just look back with our eyes open, it’s plain that, depending on who pays your salary, we’re about to enter either a Media Apocalypse, or the Opportunity of the Century.

Either way, get out the popcorn. We may have seen this movie before, but it’s always a good ride.

I welcome your comments below or contact me directly: jim@rides.tv.