Television has been trying to grow up and be a projection medium since its inception. With the advent of digital, the little box of light and shadows has finally gotten its big boy pants and even whipped its big brother, film, to take over supremacy in the theatrical world.

With the end of photochemical film projection upon us, it’s hard to believe there once was a time when the use of electronic acquisition and projection for large screen theatrical exhibition was unusual if not unthinkable. Since the beginning of the movies, thirty-five milimeter (35mm) film was always the benchmark by which all acquisition and projection systems were measured.

But in the early days of television, there were scientists and inventors who were trying to put video on the big screen. Up until the beginning of World War II, no one knew which way television would go. Would it be a theater-going experience or an addition to the home?

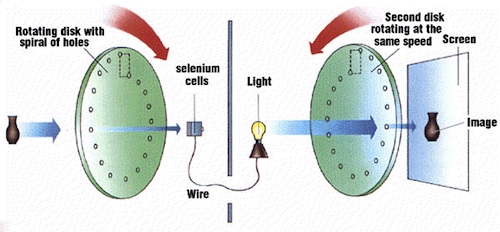

Cinematic film predates television technology almost half a century. Because film was perceived as being of a higher technical quality than television, the electronic technology has always been in the position of playing catch up to film’s larger, richer, more colorful images. Television was limited by technology in those early days. Mechanical devices using a “Nipkow Disk” rotated at high speed in front of a photoelectric cell (see drawing) to produce the scanning effect. Over the years, the system became known as mechanical television (see my PVC article on the development of “Mechanical Television” here).

The Nipkow disk is a rotating disk with holes punched at regular intervals in a spiral configuration. When spun at high speed, light shining through the holes appears to scan an object.

Because the number of holes in the disks were limited by keeping the size of the disks within a practical range, the systems were limited to about 30-60 lines of resolution (although later systems managed to get to the 200 line range using huge disks). All the early projection systems up to just before World War II used some form of spinning disk technology.

Only a decade after radio began and while movies were still finding their voice, the first demonstrations of large screen television in a theater setting were taking place. KDKA in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, had made the first scheduled radio broadcast on November 2, 1920, reporting the Harding-Cox presidential election results. Seven years later, in 1927, Warner Brothers released “The Jazz Singer” and movies had learned to talk. Three years after that, on May 22, 1930, the first successful demonstration of a live image on a theater screen took place. The General Electric Company, under the direction Dr. Ernst Alexanderson, demonstrated television pictures at the Proctor Theater in G.E.’s hometown of Schnectady, New York.

The General Electric demonstration on May 22, 1930. The screen is 6ft X 10ft. From the Early Television Foundation website (earlytelevision.org)

The projected image was only six foot square and the pictures would be considered crude (and probably unwatchable) by today’s standards. But it was impressive enough to make page one of “The Film Daily” as the motion picture industry watched the development of television closely. “Theater Television Successfully Shown” said the headline. “Television as a means of providing mass entertainment from a central studio to theaters throughout the country was shown publicly in a theater for the first time yesterday,” the article went on to say.

There are some scattered references indicating an even earlier test. That story claims a television broadcast was transmitted from NBC’s studios to a theater on 58th Street in New York City on January 16, 1930, using the experimental television station W2XBS (today’s WNBC).

However, as Albert Abramson says in his book “History of Television – 1880 to 1941,” “Such references should be regarded with caution” and goes on to explain he can find no references in the journals of the parties involved.

However, my own research turned up a reference to that test in the August, 1949 edition of the Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (forerunner of SMPTE). In his “Progress Report – Theater Television,” Barton Kreuzer, Vice Chairman of the RCA Victor Division of RCA, states that in January of 1930, an RCA system “provided a 60 line picture with reasonable brightness on an approximately 7 ½ X 10 foot screen, using a rotating-lens disk, Kerr cell, carbon-arc method.”

Knowing RCA’s proclivity to publicize its accomplishments through an active public relations machine, it is surprising there was no press coverage of the event, no doubt fueling Abramson’s position. However, it is possible the test may not have been all that successful. In his presentation, Kreuzer states, “The need for further work was indicated, about ten years’ more!” The explanation point is Kreuzer’s.

Alexanderson’s demonstration, on the other hand, held over a hundred miles from New York City, was enthusiastically covered by an interested press hungry for any news on the development of television. In addition to the aforementioned “Film Daily” piece, the event was covered by the ubiquitous “Radio News,” the Hugo Gernsback publication that was an early cheerleader for television.

That article, written by Edgar H. Felix for the September, 1930, edition used superlatives like “spectacular” and “startling” to describe not only the size of the picture but the fact it was so much better than the “best one-foot image heretofore seen at laboratory demonstrations” and goes on to report “the range of brilliancy of illumination seemed to be about half that to which we are accustomed from motion pictures.” Keep in mind the author is talking about an image that was only forty-eight scan lines at sixteen frames per second. He later estimates about one hundred lines would be clear enough to offer “permanent and pleasing entertainment of a commercial character.”

Another contributor to large screen television and contender to the prize of demonstrating the first large screen projector was Ulises Sanabria of Chicago. While I must doubt the references I’ve found that Sanabria was the first to successfully demonstrate large screen television, there doesn’t seem to be an argument he made the best ones. In an article in “Everyday Science and Mechanics” from November, 1931, the writer, H. Windfield Secor, references a Sanabria demonstration of “surprisingly clear television images six and one-half feet square” that took place “last spring.” That would indicate spring of 1931. In the same article, Secor aludes to Alexanderson’s successful demonstration as if it took place before Sanabria’s “but the interesting and surprising feature of the Sanabria demonstration was the fact that the images… are all of excellent quality.”

According to Peter Yanczer writing on the EarlyTelevision.org website, Sanabria also created “interest in television amongst the publc by providing demonstrations of large screen television”. Around 1933, he took his television projection system on the road, demonstrating a ten foot square (and by 1934, with improvements, thirty foot square) picture in cities all over North America. Yanczer states the Nipkow disc for his projector was made of cast alumnum, weighed 120 pounds, was 45 inches in diameter and two inches thick and contained 45 lenses.

Cathode ray tubes (CRT’s) were in their infancy (an invention of German scientist Karl Braun in 1897 to visualize alternating currents thereby making it the first oscilloscope). Applications for television wouldn’t come until later. But the electron scanning process that became the key to electronic television’s higher resolutions severely reduced the brightness of large screen projection systems.

Braun Tube (circa 1900). First cathode ray tube. From The Cathode Ray Tube website (crtsite.com/). Used by permission.

Within a few short years, cathode ray tubes and electron beams became the solution for exhibition of the television signal allowing a significant increase in the number of scan lines to resolve the image. The increased clarity of a 441 line system caused it to be dubbed “high definition” television. In 1940, members of the SMPE witnessed the last major test by RCA before the war interrupted further work. A demonstration was held at the New Yorker Theater in New York City. The 441-line picture was shown with low brightness on a 15 X 20 foot screen. A year later, on April 30, 1941, The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) approved the first National Television Systems Committee (NTSC) recommendation of standardizing the American television system to 525 scan lines (interlaced) at 30 frames per second and authorized commercial television broadcasting to begin on July 1, 1941.

Aside from being the first all electronic projector (no spinning disks), the RCA test is significant in that after the war, engineers were able to recondition the same system to the new 525-line standard and, on June 19, 1946, used it to televise the Joe Louis – Billy Conn heavyweight championship rematch to a crowd of 3000 gathered on the lawn of the RCA Laboratories in Princeton, New Jersey.

RCA Television Projector. From the Early Television Foundation website (earlytelevision.org)

The European Broadcast Union (EBU), with it’s 50 cycle electrical standard opted for 625 lines at 25 frames per second but both systems still remained well below the resolution of motion picture film.

As soon as the war was over, companies saw their defense business begin to slide. Many advancements in electronics were made during the war and television was one of them. By the end of the war, television was assisting in guiding bombs, steering aircraft, training troops and providing remote viewing of dangerous situations. Reinventing the electronic research and many resulting applications to come out of the war effort, manufacturers retooled their operations to adapt defense developments to civilian use. The American consumer was the beneficiary and electronic television became one of the byproducts of the war effort.

Research in large screen television resumed but it quickly became obvious television would be a home product as television receivers from seven to twenty one inches began to fly off dealer’s shelves and into the homes of the American public, much to the chagrin of the motion picture industry. Film studios that had been looking at television as a replacement for film or at least an adjunct to it, now saw it as a fierce competitor. Ticket sales plummeted in cities where television was available. Although some film studios still thought there might be applications for television that would help their bottom line.

This was the reasoning behind 20th Century Fox’s investment in the Swiss company, Eidophor. Spyros Skouras, president of Fox from 1942 to 1962, was quoted in the April 22, 1950, Harrison’s Reports and Film Reviews as saying in reference to television, “…this so called threat will be converted to the greatest stimulant our industry has had since the advent of sound.”

The conception of the Eidophor system came from its inventor, Professor Fritz Fischer in 1939. He studied how electrons were used to scan the face of the phosphors on CRT tubes and realized that in order to overcome the largest detriment to theater sized television – the limitation on brightness – a new surface for the electrons to bombard had to be found. He did so by using a thin film of oil.

Eidophor Projector (circa 1946). From the Early Television Foundation website (earlytelevision.org)

The simple explanation of how the Eidophor process differs from a cathode ray tube is when electron beams encounter the phosphors of a CRT, the phosphors merely glow. When they land on the oil of the Eidophor tube, they react by forming ridges and valleys. This creates an image in relief. By illuminating the charged oil surface with a very bright carbon arc light, the portion of the image where the oil forms peak ridges will reflect the light onto the projection screen (the white areas) and the portions where valleys form, the light will reflect back into the lamp (the dark areas).

The Eidophor came into being during a time of turbulance at 20th Century Fox (indeed, all of the motion picture industry). Concurrent with Eidophor’s development as a way to extend the use of motion picture theaters to other forms of entertainment and communication, Fox was also looking for ways to lure motion picture patrons back into those same theaters. Because television was locked into an almost square format similar to the Academy film ration of 1.33:1, the other research and development going on at Fox was on wide screen film technologies.

The two missions became intertwined when Cinerama appeared. Cinerama used an unwieldy system of three film projectors and a seven channel magnetic sound reproducer all running in sync and illuminating a screen that was curved in a 146 degree arc to produce a 2.59:1 aspect ratio, The image was deeply immersive for the film audience covering virtually the entire field of human vision. A classic scene from the original Cinerama production “This is Cinerama” puts the camera (and therefore the audience) on a roller coaster. With nothing else to guide them other than the three strip film image and seven channel soundtrack (no special low frequency speakers or seat vibrators), 1952 audiences swayed back and forth in their seats in time with the movement of the roller coaster.

Original trailer for “This is Cinerama” reworked for new Smilebox system to imitate Cinerama experience and allow films to be shown on wide screen televison.

But Cinerama was a flawed system, with the lines of demarcation between the various strips of film plainly visible (although later films attempted to hide them with vertical elements of the scene such as tree trunks). Also, due to its complexity, it broke down a lot. “Breakdown Reels” were shipped with every Cinerama movie. The reel would keep the audience in their seats while the projection crew (it took five people to run Cinerama films) hurriedly repaired the problem. The public flocked to theaters in droves to see the “miracle of Cinerama” and the studios, particularly Fox, took notice.

According to a Variety article on March 10, 1954, Cinerama unexpectedly announced its intent to adapt Cinerama to closed circuit theater television. Fox engineers working on the Eidophor project suddenly faced with the formidable task of adapting the Eidophor to a panoramic format covering a 63 x 26 foot screen using just one projector. However, even though Variety reported on January 7, 1953, Fox was “giving serious consideration to ways and means of achieving a Cinerama-type effect with its Eidophor color theater system,” no records seem to exist that a demonstration of such a system ever took place.

Even as good as the Eidophor system was, it was still limited to the scanning technology of an analog television system. It could not hold its own against the resolution of the wide screen film formats. Fox eventually withdrew its participation in the Eidophor project and concentrated on pushing Cinemascope, the 2.35:1 theatrical film format we are all familiar with today. The motion picture industry jumped on board, many with their own proprietary formats. Video projection was left in the dust.

NASA Mission Operations Control Room (MOCR) at Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas. The four screens flanking path of the spacecraft are Eidophor projections. NASA Photo

The Eidophor projectors that were manufactured were used at sports venues, outdoor concerts, NASA Mission Control and about 100 theatrical venues that were doomed when the FCC denied theater owners their own UHF frequencies to use for meetings and program distribution. By the 1990’s, other technologies were surpassing the Eidophor. As digital gradually took hold, the industry edged closer to the tipping point we are seeing now as studios cease the distribution of 35mm prints and the mechanical projector – relatively unchanged since its invention by Charles Jenkins in 1894 – no longer occupies the projection booth… if the projection booth even exists at all.

Today all the dreams of those pioneers from 1930 and on through the 40’s and 50’s have come true. Local movie theaters bring the Metropolitan Opera live to audiences far from the New York stage where it is produced. “Rent this theater for your next business meeting” is one of the ads routinely seen on screens before the movie previews begin. Sporting events from championship fights to soccer matches light up movie screens in those hours where the screen would normally be dark. And you can still go see a movie there, too… in spite of television.