All of us use gain at one point or another. Positive gain saves us when we end up shooting in a dark location, and negative gain makes us feel slightly superior because we’re giving our client an image that is remarkably noise-free. But nothing is for free – you should definitely think twice before you hit that gain switch, because it’s not just a matter of boosting or hiding noise. You’re reducing your dynamic range at the same time, and that’s not something we should do lightly.

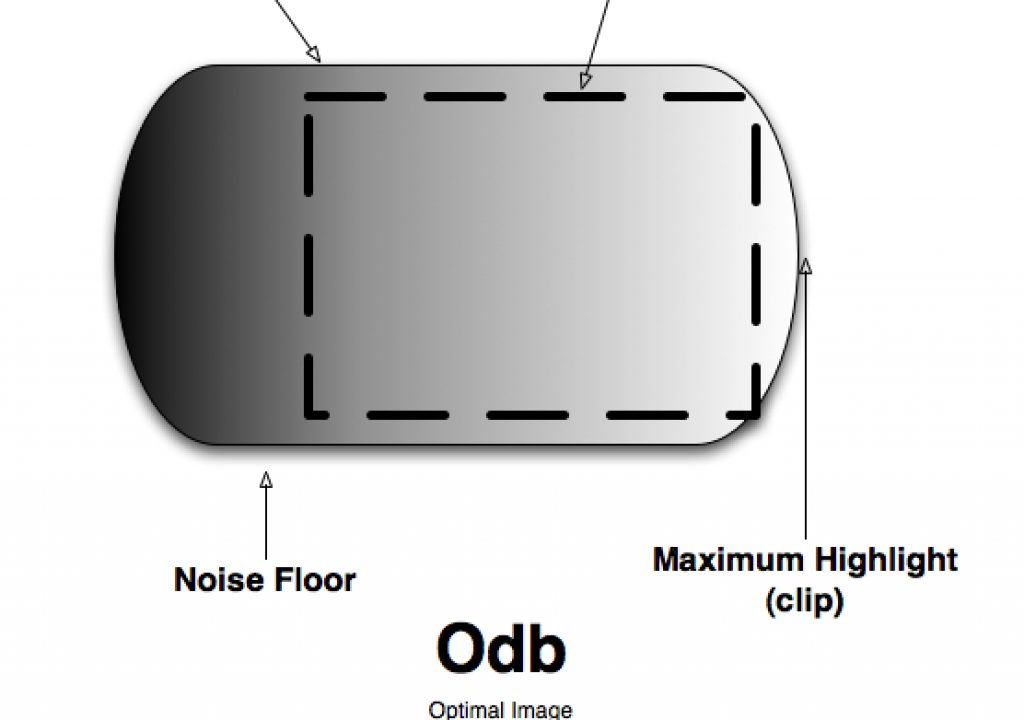

The sensor sees what it sees, and that’s it. The image we see through the viewfinder can be thought of as a “window” through which we view data collected by the sensor. The gain switch moves that window up or down the sensor, but at the expense of pushing highlights or shadows out of the range of that window. The manufacturer sets that window in a sweet spot: just above objectionable noise on the low end and encompassing sensor saturation, or white clip, on the other.

Positive gain shifts the window downward, brightening highlights and mid-tones by pushing the window deeper into the noise floor. But it also pushes the highlights outside the range of our window. That may be okay if you’re shooting a low contrast low light environment without any highlights, but if you do have a lot of highlights they are going to clip a lot sooner than normal.

You’ll probably also see a lot more noise in the blue channel. Camera manufacturers set black at a point that’s far enough above the noise floor that noise won’t be objectionable if the camera is looking at a dark scene or object. By boosting gain you’re not just trying to make the image brighter, you’re making a conscious decision to push your window deeper into the noise floor–knowing that there’s still some kind of image down there but that it’s not going to be very clean. Silicon sensors are least sensitive to blue, and as most cameras are balanced for tungsten light, which has a lot of red and not much blue, the blue channel already has added gain to boost it to the level of the red and green channels. It’s easy to see how much blue noise is in the image if you have a professional monitor: selecting the “blue only” calibration mode isolates the blue channel, making it easy to see how much blue noise is hidden in your picture.

Negative gain has long been thought of as a no-cost way of reducing noise in a video or HD image. But nothing comes for free: negative gain simply moves the window in the other direction, right out of the sweet spot. Now instead of cutting highlights, the way a gain boost does, the gain decrease reduces shadow detail. Under certain conditions, such as green screen photography, this may be acceptable as it’s fairly easy to light the shadows a little brighter to compensate. But it may not always be desirable to reduce the dynamic range of your camera just for the sake of a little less noise.

Another interesting side effect of negative gain can be seen in the Panasonic SDX-900. When first released a number of owner-operators commented that in -3db gain they couldn’t actually get highlights to hit 100% on a waveform monitor. Subtracting 3db from the saturation point of the sensor resulted in a signal that could never physically reach 100%. Those of us who set our zebras at our near 100% for run-and-gun shooting found ourselves in a bit of trouble as our highlights never showed zebras, no matter how bright we made them. We could push highlights right up to overexposure but they’d never quite hit 100%, although they’d still be white nasty highlights with no usable detail. The zebras were effectively useless unless we lower them to to 95% or so.

As best I can tell, negative gain exists just because it can: positive gain is occasionally useful, so why not offer negative gain as well? The Sony F35 actually offers -6db of negative gain for a very, very quiet image–but at the price of shadow detail. That’s a great tool for quieting green screens under controlled lighting conditions but it’s probably not a good idea to use for everyday shooting.

0db exists for a reason: that’s typically where you will get the maximum possible dynamic range out of the camera. Nothing comes without a price, so think carefully next time you boost or reduce gain. In HD nothing comes for free.